Microsoft Ability Summit aims to bring ‘next wave’ of technology to empower people with disabilities

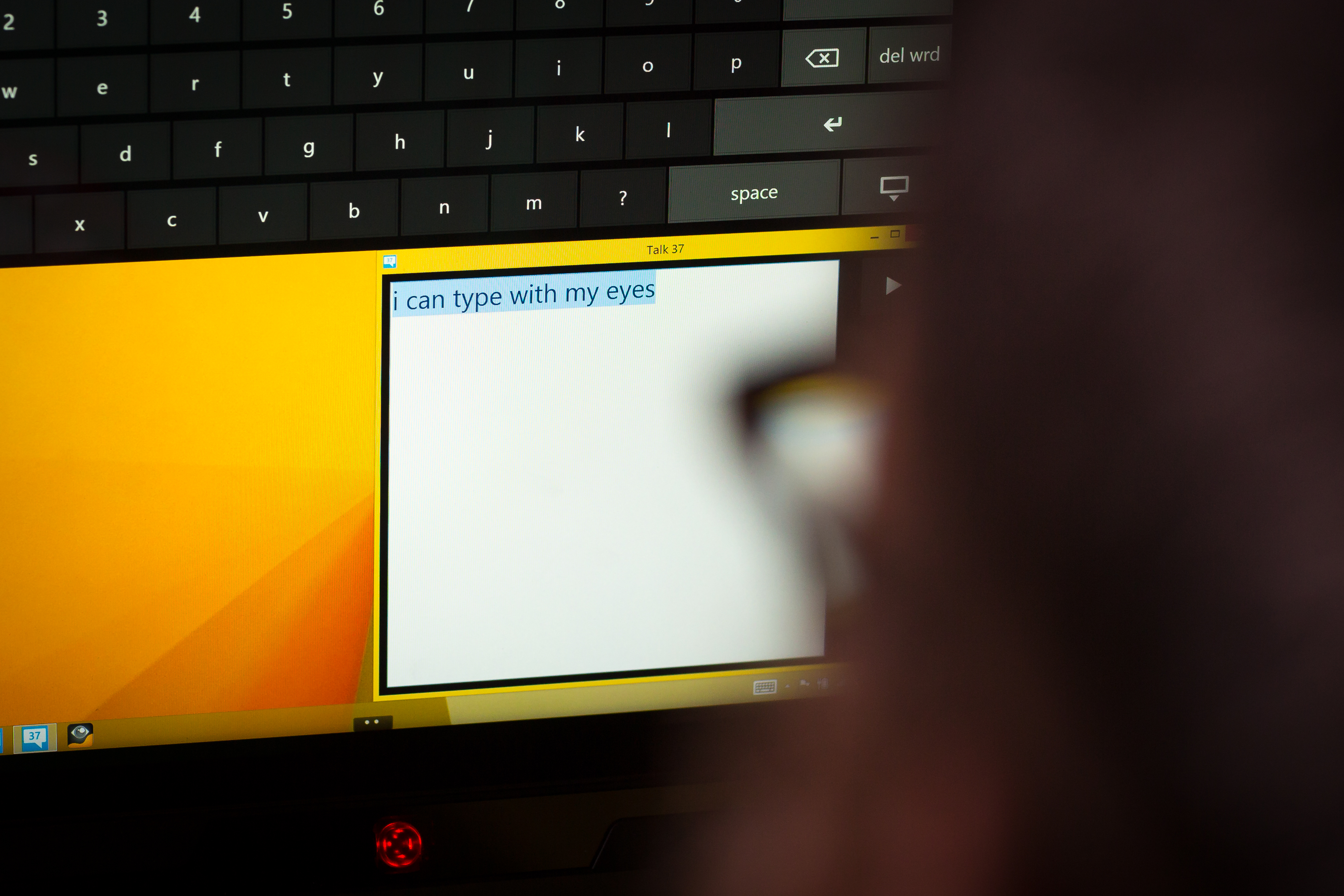

The Surface tablet with the slim black bar attachment on Jay Beavers’ desk can do an incredible thing: Give a voice to someone who has lost the ability to speak or move their limbs — all by tracking the person’s eye movements.

But that’s not enough for the software engineer lead and his team at Microsoft. They’re working to make it better, faster and easier to use so that people living with ALS, spinal cord injuries or other disabilities can have more natural conversations without frustration.

“If you look at the technology for people with ALS, there’s more we can do,” Beavers said. “Our ultimate goal is to empower people with ALS to do more — talk more easily, play with their kids and move their wheelchairs independently.”

Empowering people with disabilities is the driving force and goal behind Microsoft’s Ability Summit this week, when the company’s engineers, designers and other tech pros will work side-by-side with people with disabilities from inside and outside Microsoft, parents and other accessibility advocates to “create that next wave of great products and services” to empower people, explained Jenny Lay-Flurrie, senior director of the Trusted Experience Team and leader of the summit.

The fifth annual event, beginning Tuesday, is a way to bring Microsoft’s approach to diversity and inclusion to life. “We think about how we imagine stuff, build amazing new products and services, and enable people with disabilities to do more and build more inclusive workplaces,” she said. “We have an opportunity at Microsoft to empower the world.”

The summit features a hackathon that will have teams building creative new accessibility projects well into the wee hours of the night, and a career fair will link people with disabilities to new opportunities while helping to bring talent and valuable insights to Microsoft.

“If we’re going to build great products and services, we need to think inclusively,” said Lay-Flurrie, who is chair of the disAbility Employee Resource Group and is also deaf. “We need to have people who understand and have empathy to bring that level of expertise. Put simply, we need people with disabilities at Microsoft.”

Beavers’ team formed in the momentum of an innovative project that won the grand prize at last year’s //oneweek Hackathon, a company-wide effort to encourage creative ideas. A group of volunteers known as “Ability Eye Gaze,” inspired by former pro-football player Steve Gleason and his life now with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, developed a wheelchair that could be controlled with the user’s eyes.

But what Beavers’ team, the Microsoft Research Enable group, learned in their recent conversations with many ALS patients is that being able to communicate with loved ones can be much more important than mobility.

“When people lose the ability to speak, they lose their ability to interact with the world and can lose their will to live,” explained Beavers, who added that as a software engineer with no medical background, he’s “learning a lot.”

An eye gaze speech-generating device lets the user type words on an on-screen keyboard by simply looking at each key. A camera — like the black bar on the bottom of Beavers’ prototype — tracks the person’s eye movements. The device then reads the words aloud.

The technology has been around for a while in various forms, and many Microsoft partners are doing great work with it, but typing can be slow, Beavers said. Communicating at four words per minute can dampen any hopes of having the kind of casual conversations that families usually share.

His team has come up with a few different prototypes with “word prediction,” the ability to complete words quickly after input of just the first few letters, in an effort to make it much faster. They’re also working on a way to customize it so that it can learn words and phrases someone says often and become increasingly better at guessing them and filling them out quickly.

A man living with ALS in Bellevue, Washington, is the first to test one of their prototypes. It’s been tough in these very early stages, but the team is passionate, and Beavers is confident that with Microsoft’s dedication to the effort and the level of expertise on his team, they’ll achieve their goals of empowering people with ALS.

“It’s deeply satisfying that we can bring the same talent, quality and thought leadership to help people with disabilities that we bring to Office, Windows and Surface,” he said.

In Microsoft’s Operating Systems Group, another team is working on a technology to help people around the world who are partially or fully blind. Accessibility Group Program Manager Brett Humphrey wants to help ease something more challenging than many might realize: Communication between visually impaired people and those who can see.

Growing up in a small South Dakota town, Humphrey was the only legally blind kid in his grade school. He recalled, “I spent a lot of time teaching people how to work with me.”

“To me,” he said, “it’s about, how do we not only help the individuals with low or no vision, but how do we help integrate … people who have vision and those who don’t?”

His team spends their days working on Narrator, a screen reader included in Windows that helps identify and interpret what is on a computer screen to someone who can’t see it by reading the text aloud. While it may seem straightforward, the challenges are seemingly endless.

Picture a typical meeting at the office. When a coworker explains something on a chart or another shares something in a specific place on a website, you need to be able to find what they’re pointing to instantly to participate in the discussion.

Or consider what you do when faced with a brimming email inbox: Quick scanning. Which items are urgent? Which can be handled quickly? Which should you leave for later, when you have more time?

Imagine being a visually impaired student who needs to write a term paper. One of the biggest stumbling blocks for such projects is formatting, Humphrey says. It’s exceedingly tricky to work with indents, numbered lists and other features of a polished document when you can’t see them.

“There are lots of tasks you take for granted visually,” he added.

His team talks extensively with customers and finds out which tasks users “get stuck” on. They consider ideas for getting over some of the hurdles and work with developers to create solutions.

They’re currently working on a way to use multiple voices, perhaps at varying volumes, or sounds coming from distinct locations on the audio spectrum to allow users to get more information at once, making tasks much more efficient. They’re also exploring ways to summarize data, something that could give users the gist of their emails without having to take the time to listen to every word of each one.

The team is now partnering with Microsoft Word and Outlook teams to improve screen-reading for those applications and will work closely with other Office teams over the next few years.

Humphrey’s low vision, a result of prematurity at birth, requires him to use magnification on his computer; he uses a screen reader to get through email and about half of his other work. His goal is to help make life more enjoyable and productive for people who have low or no vision, but he says what drives him is much broader than that.

“I like the potential of solving problems, not just for those who are visually impaired, but for everyone who touches our operating system,” he said. “Today, when I look at what people call accessibility, the truth is, it’s really just a different form of usability.”

The work of Humphrey’s team is just one effort at Microsoft that’s part of the Ability Summit’s theme — inspiring people to “Imagine, Build, Enable,” Lay-Flurrie said. They are “helping us think through how we build,” while the work of Beavers’ team began with imagining something that had never been done before.

The summit’s focus “is really that connection between people and technology,” she said. “We have the opportunity to create technologies that are not only innovative, but truly do empower.”

Lead Photo: Jay Beavers’ face is reflected in a device that can drive a wheelchair using eye gaze technology. Credit: Scott Eklund