Editor’s note:

References and hyperlinks to some products have been removed since publish date due to changes in product availability.

REDMOND, Wash., Aug. 24, 2000 — When Isabella Carniato told her college classmates and professors she was going to work for Microsoft’s SideWinder gaming device group, they were shocked. After all, Carniato, a senior at the time at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada, was studying architecture and political science. And, of course, she’s a woman. How did she win entry into the traditionally male-dominated world of computer games? And why would she want to?

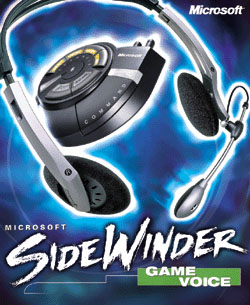

The answer is Microsoft SideWinder Game Voice, the latest incarnation of an online gaming product that she helped develop and that promises to change the way people play their favorite computer games. The first device of its kind, Game Voice allows online gamers to talk and play over a single Internet connection, as well as control games with voice commands. It also offers a control pad to organize voice chats and includes the built-in software to operate all of these functions.

“Game Voice is the only product that puts all of these pieces together in a tightly integrated package,” said Carniato, who is now marketing manager for Game Voice. “To create a similar device, you’d have to go out and buy headphones, a microphone, and speech recognition software, as well as download chat software. And you still wouldn’t have the control pad, and you wouldn’t have the software for contacting your friends and managing conversations.”

Microsoft released Game Voice today after almost a year of development. It is available in stores and online at http://www.shop.microsoft.com/ and numerous other sites, including http://www.gamestop.com/ and http://www.ebworld.com/ .

It’s a big day for Carniato, but it’s not the biggest. That honor goes to the day in December 1997 in Ontario, or more accurately a snowy winter night, when she helped sow the seeds for Game Voice.

The Idea

Carniato, 28, and her husband, Paul Newson, were sitting around the kitchen table at the home of their friends Rod and Joanne Toll. The four were playing poker, but the main topic of conversation wasn’t cards — or the raging heat from the new fireplace. It was how both men and occasional teammate Carniato had gotten trounced the night before playing “capture the flag” in the online game Quake II.

Carniato and Newson were playing from their apartment. Toll was playing from his home across town. Since they were using their single phone lines to connect to the game, they couldn’t call one another to strategize. They had the option of typing messages. But they needed their hands to type game commands and to manipulate their computer mice to keep their characters alive in the fast-paced game.

During the poker game, someone — no one remembers whom — asked the questions that would change their lives: “Wouldn’t it be cool if we could have talked to each other during the game? Is there a way to talk while you are playing?”

At the time, the answers were “Yes” and “No.” Yes, it would be cool but, no, it wasn’t possible to talk and play over a single phone line. Devices available to talk over the phone line used too much of the line to also run the game.

After spending many nights dreaming up ambitious but impractical scenarios for computer games, they realized this was a problem that needed solving.

“If we were having this problem, we figured other people must be having the same problem,” Carniato said. “It couldn’t be isolated to us.”

A good omen confirmed her suspicions: she was the big winner that night in poker.

Developing the Solution

Newson and Toll, who had both graduated the year before from the University of Waterloo, dedicated their spare time over the next few weeks to devising a solution. They created software that allowed voice conversations and the game to travel across a single phone line without detracting from the quality of the game.

They installed the software on their computers, loaded up a game and tried to talk to one another. What were their immortal first words?

“Test, test, test …God, it works.”

“I remember thinking, `I’m going to wish we said something special,'” Newson recounted recently.

They spent the next few months developing keyboard controls and completing their prototype. They called their creation Battlefield Communicator and their new company ShadowFactor Software.

Carniato, still attending classes at Waterloo, started developing a marketing strategy, getting the word out to Internet gaming sites, and creating a Web site gamers could visit to download a beta version of Battlefield Communicator —- or “BattleCom” for short.

They hoped for a few hundred inquiries. They received 2,000 emails from interested gamers in the first 48 hours. Before long, they began selling downloadable versions of BattleCom for $25 each.

“We had to upgrade our servers because we couldn’t handle the load,” Carniato said.

The Next Step

With several copycat products hitting the market, Microsoft purchased ShadowFactor in June 1999, lowering and eventually eliminating the charge to license and use the software. The company also hired Carniato, Newson and Toll to help expand the potential of their creation.

Carniato went to work marketing SideWinder products and expanding the scope of BattleCom. Newson and Toll began improving BattleCom’s computer code and incorporating its voice chat capabilities into Microsoft’s DirectX coding, thus allowing game developers to add voice chat into their products. Their hard work, along with that of a team of Microsoft employees, comes to fruition today with the release of Game Voice.

Isabella Carniato, Game Voice marketing manager, plays Age of Empires II, issuing voice commands to the game and verbally communicating with her teammates and opponents using the Game Voice headset and eight-button control unit, which includes five customizable channels.

Game Voice: Combining Best of BattleCom with New Features

Game Voice retains BattleCom’s voice chat features — including the ability to talk to as many as 64 people at once — and adds a control pad to better manage all of these voices. Not much bigger than a hockey puck, the pad allows gamers to organize conversations into as many as six groups and switch among the groups using buttons on the pad.

Game Voice, which also comes with a microphone/headphone set, allows gamers to share strategy privately with teammates on one or more channels and torment members of opposing teams on other channels. Another button allows Game Voice users to talk to everyone at once.

Game Voice’s new voice commands allow gamers to control play using pre-stored or customized spoken directions. If gamers want their character to build a house, they can simply say, “Build house.”

Unlike some voice recognition systems that require users to provide voice samples, Game Voice’s software works phonetically, matching each user’s spoken words to the letter sounds stored in its memory. If users pronounce words differently — or want to create a name for a weapon or an action — they can type in a new preset command.

Carniato said gamers, for example, might not remember the French term “trebuchet,” the name for a type of catapult used in the game “Age of Kings.” “If you want to call it catapult, type catapult into the preset memory. Then every time you want to use this weapon, just say ‘catapult.'”

Voice commands free gamers from memorizing the combinations of keystrokes usually necessary to play games. They also speed up games by allowing gamers to create voice commands in place of complicated combinations of keyboard shortcuts, or macros, Carniato explained.

Game Voice comes with profiles for 16 different games, including Age of Kings, Everquest, and Rogue Spear. Gamers can also create and modify voice command profiles for other games by mapping the game’s keyboard shortcuts to the voice prompts they want to use, making this feature applicable to virtually any computer game.

“Game Voice doesn’t discriminate. It’s an equal-opportunity voice commander, regardless of what game you are playing,” Carniato said.

Game Voice also solves another challenge for online gamers: how to bring players together. With BattleCom, gamers had to know how to find and where to enter the ever-changing Internet Protocol (IP) address for the host of the chat session they wanted to join.

Game Voice integrates the same technology as MSN Messenger instant messaging service. A small on-screen panel tells gamers when friends are online, if they are busy or if they are already hosting another chat.

“Finding and connecting to a friend becomes a simple matter of clicking on the friend’s name and inviting them to talk,” Carniato said.

Chris Taylor, lead developer of the game Dungeon Siege, is among the avid gamers wowed by Game Voice. He predicts developers will alter their games so that gamers can better utilize Game Voice’s features.

The ability to talk while playing is Taylor’s favorite feature. But others impress him as well, such as how Game Voice allows users to talk before, as well as during, games and how it allows players to switch automatically between the headset and normal speakers.

“This is something gamers have wanted to do for years,” Taylor said. “No more crawling under the desk to change cords manually.”

Changing the face of gaming

Carniato is happy she and her partners brought BattleCom to Microsoft. On their own, they would never have had the resources or knowledge to transform their creation into Game Voice, she said.

“It’s just not possible to do this with a small company,” she said.

Carniato is also happy with her role at Microsoft. Far from the stereotypical male gaming geek, the humorous, athletic brunette drives an Italian convertible and is known for her talents in the kitchen as well as her love of skiing. She recently decided to take up windsurfing.

She began playing Space Invaders as a child on a friend’s computer, and now devotes “too much time” on the weekend and several hours a week to her favorite games, which include “Age of Kings,” “Unreal Tournament,” “Deus Ex,” and “Thief II.”

Carniato rejects the notions that women only like strategy games and dislike fantasy role-playing and first-person shooter games.

“After a long week, there’s nothing better than being able to run around and blast things,” she said with a laugh.

Although women gamers still sometimes have trouble earning respect online, Carniato’s coworkers say she has won over many a male gamer at Microsoft and at trade shows with her knowledge and love of games. She even started the first all-female SideWinder gaming clan at Microsoft.

But don’t try to tag her as a “girl” gamer. “I’m just a gamer,” she said.