Taiwan brings in generative AI to help students learn English

New Taipei City, TAIWAN – Teachers often report that students learning English tend to read and write better than they speak, as shyness and a lack of practice can hinder the ability to converse. Now, a chatbot funded by Taiwan’s Ministry of Education and running on next-generation large language models offers a way for K-12 students to get that practice, and in a more engaging way than was previously possible.

The kids in Claire Mei Ling Wu’s English class at Er Chong Junior High School in Sanchong District, New Taipei City, began using the CoolE Bot soon after it was launched in late December.

Wu has been teaching English for over 25 years. Her classroom is decorated with a world map and national flags. There are boxes of knickknacks – gifts from pen pals in Japan, India and as far away as the U.S. state of Alaska.

“Sometimes when they are shy, they don’t dare to speak up,” Wu said. However, if they can remain at their desks and speak “person-to-AI,” Wu said, they are more comfortable than coming to the front of the class or standing in front of the teacher.

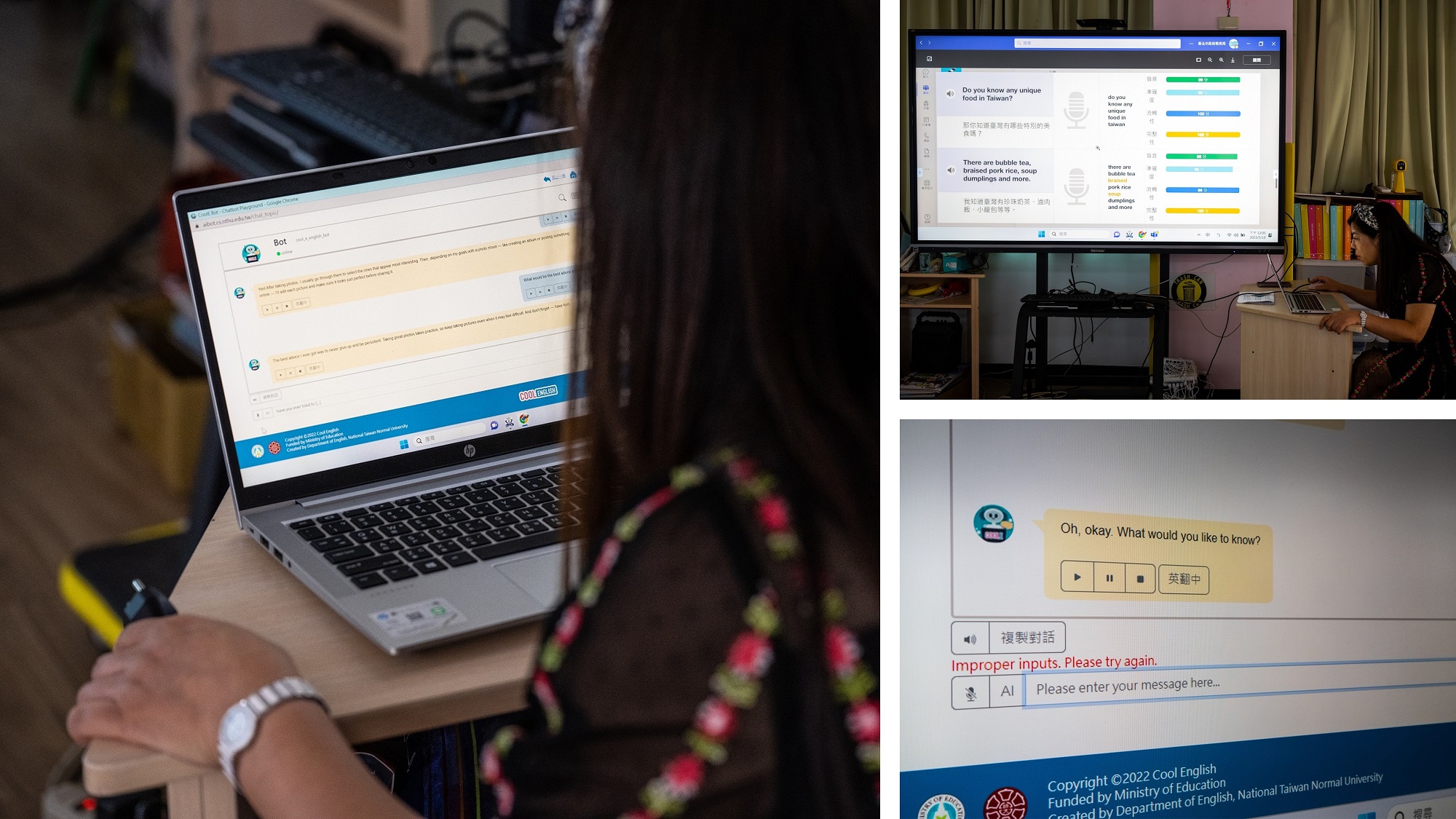

With the chatbot, which uses Azure OpenAI Service and other Microsoft AI technologies, students can pick one of many preset conversation topics – asking a doctor or photographer about their work, for example, or role-playing as a detective to solve a mystery – and off they go. While older chatbots could only provide answers that were preloaded into the system, next-gen AI can generate responses on its own.

The chatbot can also assess pronunciation, accuracy and fluency, and students can practice as many times as they like to raise their score.

If they are stumped, they can click on the “AI” button and the chatbot will suggest a question to keep the conversation flowing. A content filter keeps things from veering into inappropriate territory. If a student types or says a swear word, or something sexual, the chatbot answers in red type: “Improper input. Please try again.”

“It is interesting, and I can learn English from it,” said student Eva Zi Yu Huang, 13, eyes peeking out between long black bangs and a blue surgical mask.

Taiwan has set a goal of becoming bilingual in Chinese and English by 2030 as its economy shifts from traditional manufacturing to more data or cloud driven businesses, where the global language tends to be English. There are regional competitive pressures. For example, Taiwan competes economically with places like Hong Kong and Singapore, former British colonies where English is widely spoken.

“We want to help our students quickly enhance their English skills to compete with other countries,” said Howard Hao Jan Chen, an English professor at National Taiwan Normal University (NTNU).

In Taiwan, English classes are compulsory in public schools for one or two hours a week starting in third grade – with some schools starting as early as first grade, and that expands to up to four hours a week in high school.

That’s not a lot of time to master a language with a whole different script, grammar and pronunciation. Common mistakes in English include dropping articles, which don’t exist in Chinese – omitting “a” or “the” – and mixing up of tenses. Practice helps, but it can be hard to find someone to do that with when you’re surrounded by Chinese speakers.

In 2015, Chen and his team launched a website called Cool English to help Taiwan’s schoolkids learn English using technology. The government-sponsored website now has about 1.5 million registered users from Taiwan and beyond.

“The way that teachers teach is by reading books and listening to various materials through the Internet. But the focus is not on speaking,” said Scott Suen, a software engineer on the Cool English team. “Most Taiwanese students can pass exams and get a very high score, but if we are put in a native English environment, we have a hard time communicating with foreigners.”

To help facilitate more conversation practice, the team built its first chatbot using an older AI-based programming language.

“We quickly found it very problematic,” said Chen. “You have to type in all the possible answers for a question raised by students – thousands of sentences to reply to students intelligently. It’s not AI. It’s really labor.”

Worse, he added: “We don’t know what kinds of questions students want to ask! Students won’t want to play with this kind of silly tool.”

The project went dormant for a while. In 2022, the team heard about next-generation large language models. “We saw, wow, this is really something!” Chen said. “It was very robust. The answers are much more meaningful.”

The CoolE Bot, introduced in December, sits on the Cool English website. It uses advanced language models as part of Microsoft’s Azure OpenAI Service to engage students in conversation about a set of scenarios. The language is adjustable for different ages and proficiency levels.

The CoolE Bot uses Microsoft Azure Cognitive Service Speech capabilities including text-to-speech and speech-to-text. Students can pick multiple voices with American or British accents. And Azure provides the data security that’s particularly important when technology is used in this setting.

“It’s a closed loop Azure subscription,” said Sean Pien, general manager of Microsoft Taiwan. “All conversation, finetuning and materials are within this secure domain.”

So far, about 30,000 students a month are currently using the chatbot, racking up a total of one million conversations a month.

The team is now working on improvements, including adding avatars and new scenarios for conversations. In the future, as more advanced models are available, the tool will also be able to correct errors, Chen said.

Recently, Wu’s class used the chatbot to prepare for a video call with counterparts in Bahrain, where the goal was to practice English and learn about each other.

During the call, the Taiwanese kids tackled some big words with ease.

“The National Palace Museum has about 700,000 pieces of Chinese imperial artworks, making it one of the largest collections in the world,” said Eva, the seventh grader, in front of her class as well as the Bahrain students onscreen.

“The Longshan Temple in Taipei is a religious, political and military center in Taipei City and has become an attraction for foreign tourists in the post-war period,” a boy with spectacles named Frank Pan said.

When one student stumbled over the word “reservoir,” a chorus of voices helped her out.

After the kids played an online quiz together, the Taiwanese students were excited to ask questions they had written down for the Bahrain students.

“Are there any deserts in your country?”

“Is your school a boys’ school?”

“What kind of transportation do you have in your country?”

“Have you drunk bubble tea?”

And more.

Top image: Eva Zi Yu Huang, 13, and fellow English students in Taiwan compete in an online quiz with counterparts in Bahrain. Photo by Billy H.C. Kwok for Microsoft.