With cloud technologies available to more people around the world than ever before, it’s not only businesses who will benefit from using them. Microsoft’s investment in cloud infrastructure, such as the forthcoming NZ North datacenter region, provides significant opportunities for science and society. The digital age enables unprecedented collaboration on some of our greatest scientific and environmental challenges. Partnership to leverage the power of the cloud is essential if we want to help New Zealanders understand the impacts of our actions on our local environments and empower communities to act.

We’ve recently seen major floods that eroded an urupa in Tairawhiti and caused real problems across the motu. If we don’t take a significant leap forward in our ability to gather and use data in a more collaborative way, to understand how the environment and people are being impacted by forces like climate change, our ability to mitigate risks like these will remain far less that it needs to be.

The impacts of climate change and how this is linked to human activity have been identified as a significant “data gap” that needs addressing.

This challenge has been clearly articulated by Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, Simon Upton who said in the 2019 report “Focusing Aotearoa New Zealand’s environmental reporting system”: “Huge gaps in environmental data and knowledge bedevil our understanding of the environment, while we know the urgency to act has never been greater.”

Microsoft’s own Journey to Net Zero research, which interviewed around 800 New Zealand businesses, found that lack of accurate measurement of emissions and impacts was the key barrier to our collective decarbonisation efforts. If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it. Collaboration was one of the main recommendations to address this.

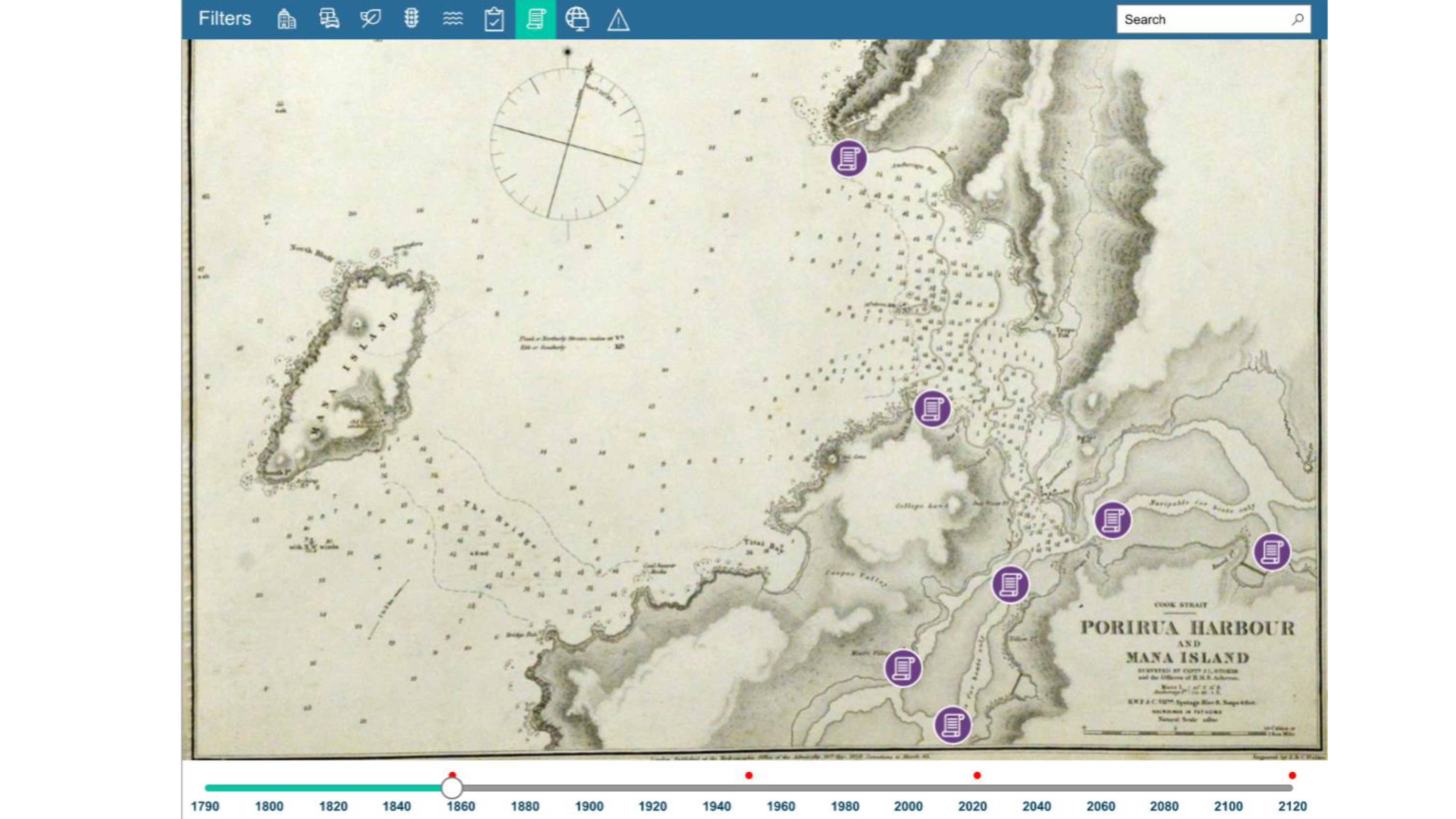

Microsoft partnered with the Ministry for the Environment (MfE), mana whenua, three local councils, the Open Data Institute and tech partner Aware Group to build a proof-of-concept digital visualisation of Te Awarua-o-Porirua (Porirua Harbour catchment) and the Kenepuru stream. Combining historic records and oral histories from Ngāti Toa with recent data and Microsoft machine learning tools, it shows what the waterways used to look like, how they’ve changed over time through human influences – and how they may change in the future.

As Natasha Lewis, Deputy Secretary, Strategy and Stewardship at MfE explains: “We wanted to create a digital visualisation and explore how combining the knowledge of mana whenua and data from a range of existing sources could be shared to enable holistic decision-making about the environment, what we take from it, and how we give back and protect it.”

While most Kiwis are aware of the need for environmental action, it’s often difficult to communicate the urgency of the problem in ways that resonate. Better tools are needed to enable and encourage faster action, to integrate different sources of knowledge and help people make informed decisions in areas like infrastructure development and environmental management.

Like Wellington City Council’s global award-winning Digital Twin initiative, the project marks the start of a unique ‘data collaborative’, showing how, by bringing together experts from various sectors, we can generate new insights and innovations and better harness data for the public good. It’s also an example of how data can be transformed into educational visual tools that inspire and empower decisionmakers to take action, capturing imaginations in a way graphs and tables can’t.

According to Suze Keith, Climate Change Advisor for Greater Wellington Regional Council: “It’s about taking what we know and squeezing the most value from it. This means that instead of talking about, for example, five more 25 degree-plus hot days in 2025, we have richer conversations saying, there will be more hot days, and for you this could mean increased distress for your livestock, building occupants, elderly parents or customers, so you might want to think about installing heat pumps, changing land use, planting trees or installing better ventilation.”

Another essential part of the project has been reflecting stories of mana whenua and their connection with Kenepuru Stream, which are often overlooked by data scientists, as Ngāti Toa rangatira, Robert McClean has observed:

“The voice of mana whenua needs to clearly shine under any light, and the history and experience of Ngāti Toa must be given prominence. This requires more information than existing online sources, as today’s mapping systems were developed and dominated by colonial government survey regimes.”

The visual demonstrator is just the start of what could be possible with collaborative efforts like this. We hope the project will inspire other organisations to collaborate on opportunities to make data more open and accessible for the benefit of society, akin to the Microsoft Planetary Computer. This is a global initiative compiling data from environmental researchers and citizen scientists to build a living picture of our world’s health. Data from the Planetary Computer was used to help create the Wellington visualisation.

Imagine if all our environmental ecosystems were supported by a shared data ecosystem that enabled more New Zealanders to take direct action to improve our environment, from protecting native species to rethinking our approach to where and how we build new developments. With limitless, hyperscale cloud now on our doorstep, there’s no longer any limit to how much data we can share and analyse here in Aotearoa. The best innovation doesn’t happen in isolation. So let’s take the opportunity to pool our knowledge more often.