Assisted by AI, a workforce of bees tracks pollution and boosts biodiversity

When Karl Wenner looks at his farm on Upper Klamath Lake in the mountains of southern Oregon, he sees a landscape in transition.

He and his partners converted part of their fields of barley into wetlands along the shore of the lake to filter runoff and protect the quality of the water that eventually flows back into the Klamath River, which empties into the Pacific on California’s coast. The project is part of a larger effort to clean up the river, remove dams and bring back salmon.

At Lakeside Farms, that transformation is being guided by a surprising source of information: the pollen collected by tens of thousands of honeybees. A Belgian start-up called BeeOdiversity enlisted Wenner, who is also a beekeeper, to help in a survey in the Klamath River Basin. Each colony, with 50,000 bees, harvests pollen over an area of more than two square miles, collecting as many as 4 billion tiny samples in a year. The resulting data creates a clear, accurate picture of the plant life and pollution present in the environment.

“I didn’t know anything about what they were going to do,” Wenner says. “I thought well, that sounds cool, what the heck, I’ll try it. And then they started sending me the data, and it was like ‘Holy cow! This is powerful stuff.’”

The bees’ data revealed rare native plants that Wenner didn’t know were there, as well as invasive species that needed to be removed to create balance.

Farmers are among a growing number of beneficiaries of BeeOdiversity’s unique system of data collection. The company now has clients in 20 countries. In Europe, public water utilities and water bottling companies like Nestlé are using the system to monitor and protect sources of mineral water. Industrial clients use the bees to check compliance with regulations and monitor the environment to preserve soils and biodiversity.

With expertise and tools shared by Microsoft and Accenture, the company has developed what it calls BeeOimpact, a system that is using machine learning to extrapolate data over much larger areas. This assesses the impact of an activity on local biodiversity. BeeOdiversity now has its first clients for this platform. In the Azure cloud, it uses machine learning in Azure Data Factory to identify areas where pesticides may be in high concentrations. This brings the benefits of bee-gathered data to much broader areas at a much lower cost.

Innovative technology and the genius of nature are working together to create a data set found nowhere else.

Saving the bees

BeeOdiversity cofounder Bach Kim Nguyen wrote his Ph.D. dissertation on the reasons behind bee colony collapses, a global problem. The causes include the use of pesticides, habitat loss and increased vulnerability to pests and diseases. When he finished his studies, Nguyen made saving bees his mission in life.

He says he’s always been passionate about these social insects and describes a bee colony as a super organism. Each of the 50,000 bees in a colony has a role, and all work together to support the hive. “They’re a good model for us,” he says.

Bees are also essential to us. Of the 100 crop species that provide 90% of food worldwide, 71 are pollinated by bees, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

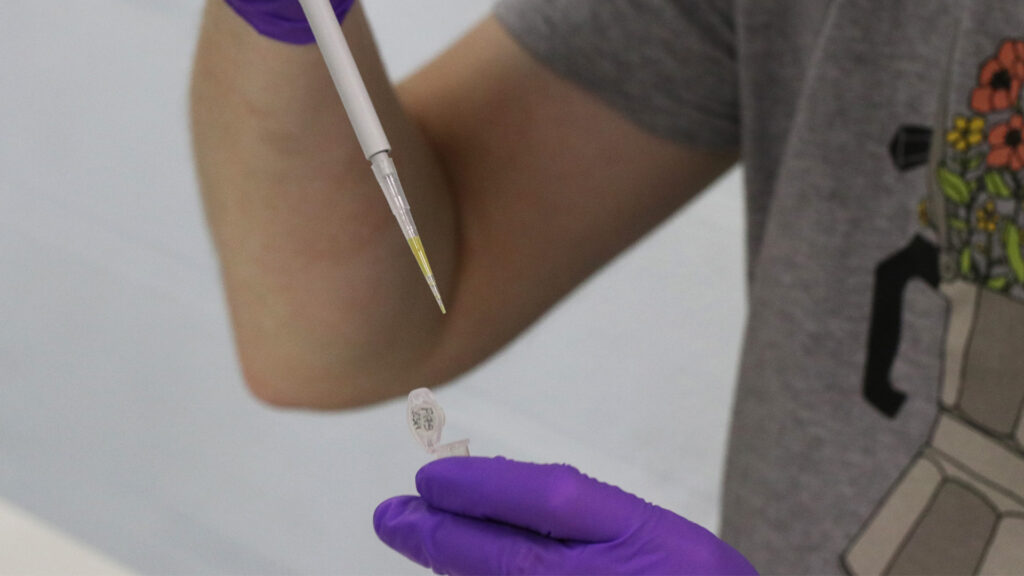

Nguyen invented a system that knocks a tiny bit of pollen off the worker bees as they return to the hive – enough for research, but not so much as to rob the bees of nutrition. Using laboratory analysis and AI models to establish some correlations between results, BeeOdiversity can identify more than 500 pesticides and heavy metals, as well as the plants in the area.

Once the data is analyzed, BeeOdiversity scientists make recommendations to clients and stakeholders to reduce pesticide use and improve the overall environment. “In that way we are working on factors like biodiversity and pollution,” Nguyen says. “And in the end, we save the bees.”

Since its founding in 2012, BeeOdiversity has won numerous awards, including an Ashoka fellowship, research funding from the European Union and being included in Microsoft’s Share AI and Entrepreneurship for Positive Impact Accelerator programs. BeeOdiversity was also selected for the AB InBev 100+ Accelerator program.

As part of that program, the beverage giant AB InBev and BeeOdiversity are collaborating on a pilot project in and near the AB InBev hops-production area near George, on South Africa’s southern coast.

Alyssa Jooste, Africa sustainability manager for AB InBev, says it’s the only place on the continent where hops for beer can be grown. Invasive plants, like pine trees, black wattle and eucalyptus, use as much as 60% more water than native species in an area where it is scarce, she says. For more than 10 years, AB InBev has been working with the World Wildlife Fund South Africa to clear areas of those species to protect precious water sources and restore native species.

As part of its pilot project with AB InBev, BeeOdiversity is using data gathered by six bee colonies to gauge the impact of the removal of invasive species as well as the presence of pesticides in the environment. The bees collect pollen at farms and nature reserves nearby. BeeOdiversity is also using DNA analysis to evaluate the soil in the area.

“The information from the soil sampling as well as the pollen and biodiversity analysis will infer how successful our clearing initiatives have been in restoring biodiversity and soil health,” Jooste says. “It will form a baseline on which we can make decisions going forward.”

AI expands data’s value

Michaël van Cutsem, the CEO and the other cofounder of BeeOdiversity, says the company has begun using a beta version of its BeeOimpact software. The system uses AI to extrapolate data to much broader areas to assess the environment at a much lower cost.

BeeOdiversity has gathered data over hundreds of thousands of acres across Europe. With the new software, it can use satellite imagery and other mapping technology to see what crops and industries are present in an area and estimate the pesticides and plants that are likely to be present. Initial testing of the software shows about 80% accuracy, van Cutsem says.

“Through this platform, we provide them with results within a second,” he says. “It enables them to screen very quickly and at a very low cost multiple sites. Then they can focus on high-risk areas, and if they want, use the BeeOmonitoring system for more precision.”

One of BeeOdiversity’s first clients was De Watergroep, the largest water utility in Flanders, the northern, Flemish-speaking part of Belgium. It has been using bee colonies to analyze the areas around its groundwater extraction points for about eight years.

The organization is trying out the BeeOimpact AI-powered platform this year. De Watergroep has 86 groundwater extraction plants scattered across the country, as well as five surface water plants. The utility serves more than 3 million customers.

“The tool they’re developing with Microsoft is interesting for us,” says Simon Six, team manager at Water Resources. “We can prioritize our fields and say OK, the risk will probably be very high in that area where we don’t have hives, and then we can move hives there and plan more detailed water analysis to identify the specific risks.”

Six says that the data is only one important aspect of the value that BeeOdiversity delivers.

“The approach of BeeOdiversity is very useful, because they do monitoring, they do analysis of the pesticides and they also check the properties of the products they find – is it a risk for groundwater or not? And the third step is stakeholder management.”

In this last step, an agronomy expert from BeeOdiversity will present the data to farmers and citizens from nearby villages and towns.

“We see that that people are really interested if you say ‘Hey, we monitor the environment with bees,’” he says, “and what do the bees tell us? The objective data starts the conversation, and, well, bees don’t lie.”

Nguyen says that BeeOdiversity’s approach is to help farmers adopt sustainable techniques without spending more money.

“A conventional farming operation cannot change in one year,” he says. “So the first thing we say is, apply the pesticide late in the evening. That way, the people nearby are not outside doing barbecue. The pollinators are not flying. And the impact is less than it was before.

“Then, most of the time, they’ll say, what’s the next step?” he says. “The idea for us is to give them alternatives. Sometimes it’s still chemicals, but with less impact and toxicity than before. After that we go into integrated pest management, and after, if they want, to organic.

“The idea is to not only work on the environment but also on the business model and create value for them,” Nguyen says.

For Karl Wenner in Klamath Falls, the data gathered by bees is already having an impact. The restoration work at Lakeside Farms is part of a bigger project to restore salmon to the Klamath River – the world’s largest dam-removal project is underway there. Salmon need clean, free-flowing water to thrive.

Because they were so impressed with the results of the larger two-year study that started in 2020, Wenner and his partners applied for another grant for BeeOdiversity to analyze data more specifically at Lakeside Farms, which consists of about 400 acres, to determine how the wetlands they created were faring.

The Weeden Foundation, which funded the first BeeOdiversity survey in the area, agreed to support a second grant. The project is also supported by the Clif Family Foundation. Since the beginning of the year, bees have been gathering data that will help guide Lakeside Farms’ efforts to be sustainable and environmentally responsible.

The restored wetland has already delivered results, Wenner says. There was an “incredible” drop in phosphorus flowing into the lake, and that is thanks to the plants in the wetland, he says. Lakeside Farms will also convert to growing organic barley over the next three years; Wenner says that can result in as much as a 50% increase in the value of the crop. So the changes make economic sense as well as contributing to the larger restoration of the Klamath River Basin.

“It was pretty much a monoculture of barley,” he says. “Now we have all kinds of stuff growing out there, and we’ll be able to monitor that with the bees. I also want bees out there because many of the plants that are most important as feed for waterfowl are insect pollinated. We are also interested in contaminants and pesticides.

“The bees will help us determine objectively what is there, and then we can take action,” he says. “There’s a lot of useful information we can gather from them.”

Top image: Morgane Dron tends the bees at the BeeOdiversity office and lab near Nivelles, Belgium. Photo by Chris Welsch for Microsoft.