Cigarette butts are poisoning shoreline animals. This beach rover may help clean all that up

Edwin Bos savored the idyllic scene: blue sea, brilliant sun and his two small children frolicking on Scheveningen Beach. Popular with tourists and locals, the 4.5-kilometer stretch of Dutch coast is filled with aquatic wildlife and grassy dunes.

But for Bos, all that beauty quickly faded amid one tiny discovery. It happened as his son, then 4, dug into the sand and raised his hand to show his father a fresh find.

“What do I do with it?” the boy asked. In his fingers, he held a cigarette butt.

“Not good,” the father thought.

Turned out, cigarette butts littered the landscape. Bos instantly realized some things. First, beach visitors needed to change their ways if they thought stuffing used filters in the sand meant the nasty scraps were now harmless. Second, he would find a way to help solve the problem.

Two years later, Bos and fellow entrepreneur Martijn Lukaart have built a mobile, beach-cleaning machine that can spot cigarette butts, pluck them out and dispose of them in a safe bin. Bos and Lukaart are the co-founders of TechTics, a consultancy based in The Hague that works to resolve social issues with technology.

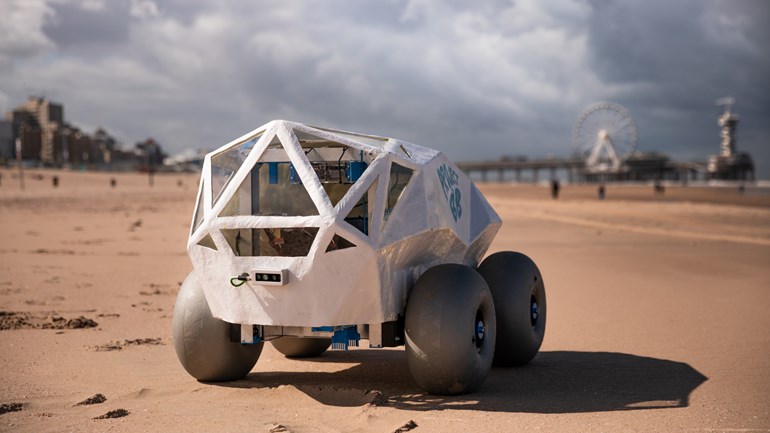

Their prototype, called “BeachBot” (“BB” for short), uses artificial intelligence (AI) to learn how to better find the strewn filters, even if they’re partially buried in sand. BeachBot has completed one demo – at Scheveningen Beach during World Cleanup Day last September. Another demo is scheduled for this summer.

“It’s such a beautiful place,” says Bos, who lives near Scheveningen Beach. He enjoys strolling the less-crowded stretches on rainy, breezy days when it feels like he has the sand to himself. “It really amazes me that all these things are just lying around.

“The filters of cigarettes are full of microplastics,” he adds. “It’s bad that these end up in nature.”

How bad? When water touches discarded cigarette butts, the filters leach more than 30 chemicals that are “very toxic” to aquatic organisms and pose “a major … hazardous waste problem,” according to a February study by U.S. government scientists. Some of those chemicals also are linked to cancers, asthma, obesity, autism and lower IQ in humans.

Every year, 4.5 trillion cigarette butts end up in the environment. The fibrous fragments, which can take 14 years to disintegrate, have become “the most frequent form of personal item found on beaches,” according to a 2019 study by Brazilian scientists. Along coastlines, they slowly poison sea turtles, birds, fish, snails and other creatures.

Many visitors to Scheveningen Beach are unfortunately familiar with an array of scattered junk along the shore – plastic caps, glass bottles, candy wrappers and all those cottony cigarette filters.

“I want my kids to be able to sit barefoot in the sand without any glass or cigarette butts lying around,” says Oscar de Grave, a financial education instructor who lives near Scheveningen Beach. “A clean beach is very important to me.”

That goal is embraced by scores of locals. To reach it, Bos and the TechTics team created the first AI-based detection algorithm that specifically sees cigarette butts. They worked with students from Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands to produce BeachBot, which relies on AI to do its job.

But teaching the bot how to find its prey requires a lot of people. TechTics must show the beach rover (and, specifically, the AI system) thousands of photos of cigarette butts, all lying about in various states, such as partially hidden, so it can recognize and remember them.

To help amass those photos, Bos and team turned to Microsoft Trove, an app that connects AI developers with photo takers through a transparent data marketplace. Trove establishes a direct photo exchange for fair market value. In this case, people can submit their photos, and TechTics directly pays contributors 25 cents per accepted image.

TechTics is seeking to eventually collect 2,000 photos via Trove. To date, it has obtained about 200 useful images.

“The system learns how to see pictures like a child recognizing an object for the first time,” says Christian Liensberger, lead principal program manager of Trove, a Microsoft Garage project.

Trove is built on that idea that people should be paid for their data – like their posted photos – rather than just giving it away on social media or communication platforms, Liensberger says. And there should be control and transparency within that process, allowing people to view how their data gets used.

“With this transparency, a lot of (Trove contributors) feel like they’re part of a team, that they’re doing it together, that they’re actually helping,” Liensberger says. “It’s important for people to contribute to something lasting.”

Trove users can choose when to participate. Trove can collect all kinds of data and is currently helping support a wide array of AI projects.

Trove’s mission also is deeply rooted in Microsoft’s commitment to Responsible AI, which seeks to ethically advance AI by putting people first.

“This BeachBot is powered by the people,” Liensberger says.

“The bot does all the legwork. It goes to the beach, and it is the hero of cleaning,” he adds. “But to clean, it needs all these people to give it consistent data input. Without that, the bot will run into new situations it doesn’t understand. Machines like this only work because of people.”

On Scheveningen Beach, the quickest way to a cleaner shoreline is via teamwork between people and mobile bots, Bos agrees.

“That’s the most interesting part of our concept – we have a human-robot interaction where the public can help make the robots smarter,” Bos says.

And along the way, as people take and share thousands of photos of cigarette butts fouling the planet, they’re also raising awareness about the waste and perhaps convincing others to stop dropping their debris in the first place.

“We believe that our robotic solution, in the end, may not be the final solution for this problem because the bigger problem with littering is still human behavior,” Bos says. “We have to make sure together we are keeping our beaches clean.”

BeachBot, which is about 80-centimeters wide, has shown it can handle part of that work. During its first demo, it scooped up 10 cigarette butts in 30 minutes. Rolling atop the sand on four puffy-looking wheels, the machine uses two onboard cameras to look ahead (to avoid people and objects) and to look down.

Once it spots a filter, it lowers two gripper arms that push the sand together and grab the filter, which is pulled up and into an internal bin. Later, people empty that bin into a trash container. The prototype is battery powered and can currently operate for about an hour.

TechTics is now creating two smaller, companion bots – “the two little helpers” – that focus only on detection. They will eventually work as a trio. The smaller bots will map the beach. When they locate cigarette butts, they can message BeachBot (or other beach-cleaning vehicles, like tractors) to request removal.

The mapping bots also will rely on photos contributed via Trove.

“We start with cigarette butts. That’s the world’s most littered item,” Bos says. “In the future, we want the robots to detect a range of other litter.” He envisions the bots working autonomously, powered by solar energy.

These are some of the fresh hopes Bos now takes to the beach. On some visits, he also carries his own set of grippers.

In his spare time, Bos takes his children through the Scheveningen dunes where they use the grippers to gather every shred of garbage they find. In a one-hour hike, they can fill an entire trash bag.

While wandering, he sometimes pictures the people who left those bits behind, who apparently think someone else will clean up their mess. And he dreams of a team of sand-roaming robots that someday may teach those same folks to take better care of their planet.

Top photo: BeachBot on the boardwalk at Scheveningen Beach. (Courtesy of TechTics.)