Technology helps farmers weather the storm (or drought) via crop insurance

Farmers around the globe may cultivate different crops and apply distinct growing techniques, but they all have a keen knowledge of weather and how it can lead to a boom or bust harvest.

Moussa Moukoro is no different. A farmer in Mali, Moukoro’s crops include millet grain and Guinea corn. But droughts have wreaked havoc with his crops – and other Malian farmers – for several years. In 2021, Mali experienced its worst drought in five years, with searing heat and low rainfall putting millions of people at risk due to food insecurity.

“If the rain doesn’t come in abundance, the crops are not working,” Moukoro said via a translator.

Farmers are among the hardest hit by weather woes – not only are they lacking the literal fruits and grains of their labor, but in some cases they are also unable to put food on their own tables. If the harvest season was unsuccessful, it meant many were back to square one, with no source of income until the next season. Nearly 400 million farms are dependent on rainfall to succeed, but only 15 million, or 3 percent, are protected by insurance.

Simon Schwall began his career in the telecom industry and saw how rural customers in Africa without bank accounts eagerly adopted mobile payment options. After a drought in 2015 left many of those customers struggling to make ends meet, Schwall thought the phone model could work with crop insurance.

He founded Oko in 2020 to provide low-cost crop insurance for small farmers, with a mission to help overcome income distribution insufficiencies for those who feed the world. The name is fitting: In ancient tribal beliefs, Oko is the name of the deity protective of good harvests. The Israeli-based start-up partnered with local phone operators and mobile payment processors in Mali and Uganda to set up the service. But to make Oko effective and impactful, there needed to be on-the-ground advocacy.

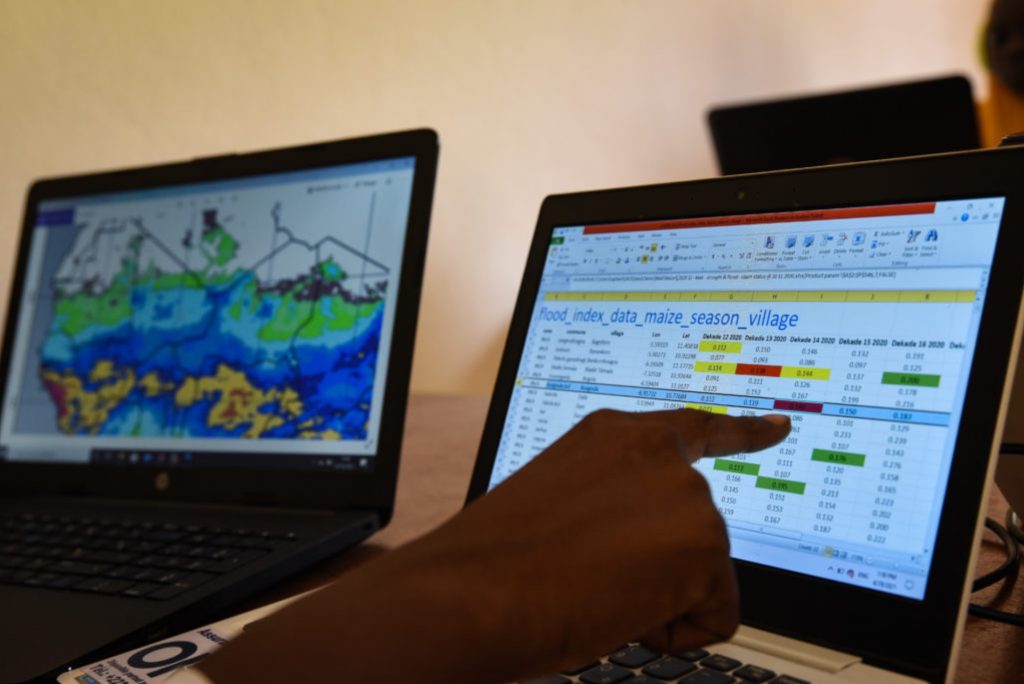

Oko uses the concept of index insurance to reduce costs. Many insurance policies have administrative costs pre-built to account for claim verification, assessments and other cost uncertainties. Index insurance utilizes data analysis and risk calculation rather than onsite inspections to build a cheaper, more accessible policy for rural customers. Remote weather monitoring takes guesswork and the human element out of the policy, allowing Oko to quickly act in the case of drought or flooding.

“We needed to talk to the end customers,” Schwall recalled. “We spent time in the field with farmers to understand what they needed. And we needed to educate them about how crop insurance works. They’ve all had a bad season or suffered from a drought. So, they could see the benefits of being insured.”

Farmers sign up for Oko using their mobile phones. On average, farmers pay around $20 (USD) to cover a full season and they average covering approximately 1.7 hectares (4.2 acres). Oko then uses historical data and weather data to analyze the insurance risk and determine the policy cost. If the real-time data shows a serious drought or flood, Oko pays farmers immediately, eliminating the need to file a claim and ensuring farmers bounce back from a poor season much faster than before.

“Oko insured both drought and rainfall and that’s why I became a member,” Sékou Coulibaly, a cereal farmer in Mali, said via a translator. “The first year, the crop was very bad for us and Oko, because of the drought, helped compensate for the damage. I have to say that Oko is very good for the farmers in the region.”

Schwall, however, believed Oko could make an even greater impact. He signed up for the Microsoft for Startups AI 4 GOOD acceleration program and Founders Hub, which helps purpose-driven ventures in Israel advance their AI solutions to create positive social transformation. Graduates of the program receive technology, connections and grants to help bring startups’ impactful visions to life.

“We were very impressed with the leadership team and their passion for making a difference in people’s lives,” said Raz Bachar, general manager for Microsoft for Startups Israel. “While reviewing Oko’s application, we started to understand the size of the problem they were addressing and the potential impact they could have on the world. More than that, the excitement was tangible when the team spoke about their solution – we could hear the emotion in their voices and see the sparkle in their eyes. They are truly inspiring.”

For Oko, Microsoft Azure’s robust infrastructure and data tools helped the company improve its customer relationship management (CRM) platform and build machine learning algorithms to better analyze satellite weather data and reduce its costs in calculating its results. Additionally, the Microsoft program provided mentorship and training on how to measure impact, plus research and development funds.

“The benefit of the program really allowed us to scale up,” Schwall said. “We were able to migrate our (self-designed) platform to Azure without really having to change our infrastructure or resources. We’ve been able to go from helping 1,800 farmers to more than 10,000 farmers. And now, we have a program with UN Women in Mali. We realized that we had a limited number of women in our customer base and we want to bridge that gap.”

Each season, Oko uses real-time satellite data and rainfall monitoring to determine how much rain is needed for a healthy harvest. If the rainfall drops below the thresholds, it automatically triggers a payment to the farmers.

“They don’t have to call us,” Schwall said. “Some of the farmers have asked us, ‘How do you know?’ We tell them on the app, ‘You suffered from a drought, click here to receive your money.’ There’s no risk of fraud.”

“It is very easy and I am super happy about their work as they provide us with critical information,” Moukoro said. “Oko is sending us information via text messages about the weather forecast. They tell us when we are going to miss rain and that information is shared with us all the time.”

If there is a drought, Schwall said that farmers use their payments to either buy new seeds for the next harvest or buy other goods they can sell in town, such as fuel. Because farmers are insured, now they can acquire microloans that help them invest further in their crops.

Even though Oko has made strong inroads in Mali and Uganda, there remains a large swath of farmers throughout Africa and other nations that Oko would like to support, as well as ensuring existing customers remain happy and engaged with the product. As climate change continues to become a major factor, Oko’s ability to react quickly and provide insurance for famers could have major impact.

“We still have things to prove,” Schwall said. “We still have the high cost of customer acquisition. We want to keep our farmers insured from season-to-season. We need them to believe it’s a good thing, so we need to validate the impact. We’d also like to grow internationally. We’d love to reach one million farmers by 2025. That’s our North Star. Hopefully we can prove that this operation is a valuable business model.”

For those farmers with their eyes to the sky and hands in the dirt, having some peace of mind that their work won’t result in a total loss if there are weather issues has been a major relief.

“Oko is doing great things for us,” Coulibaly said. “I am even doing some awareness to other farmers. The idea is amazing and they are helping farmers a lot.”

Top photo: Lassina Doumbia, a farmer in Touréla, shows some of his crops. Photo by Nicolas Réméné.