Here are some operational guidelines that we at Microsoft Stories have found to be most efficient and productive:

We hold regular editorial meetings, both for the team and with communicators across the company so everyone is aware of storytelling efforts on different channels. This helps reduce redundancy and promote cross-company amplification of newly published stories on various sites, blogs and social media channels.

We establish a clear editorial timeline and story scope from the beginning of every story. Requests for the newsroom to cover stories should go to an editor who determines the news value and whether a proposed story fits with the newsroom and company’s mission. Bringing the news team in early helps stakeholders plan and scope their project.

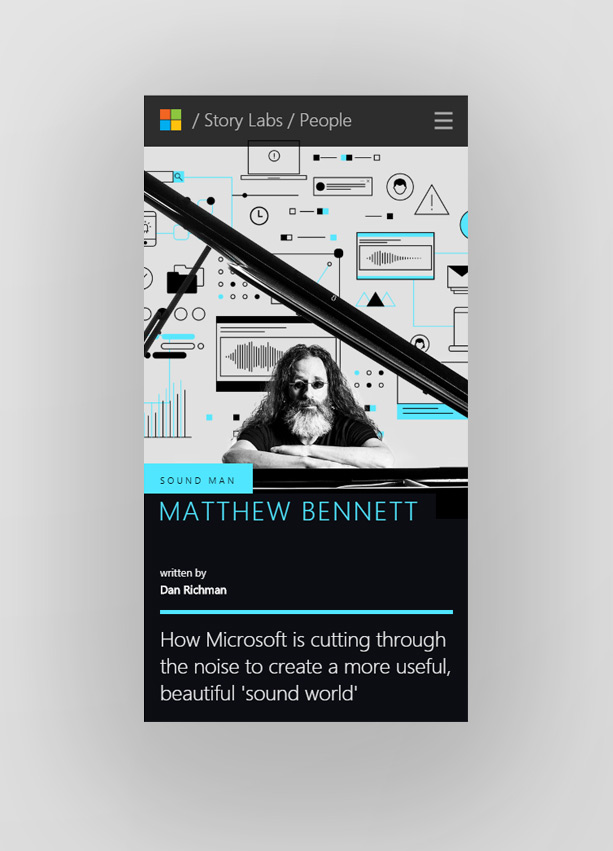

Editors and stakeholders decide early on whether the story will be short, mid-length or long. They consider whether it would do well with interactive features such as a quiz or poll, and with video, photos or sound samples.

Editors assign stories to writers, with guidance on the story’s goals and which stakeholders are overseeing it. Understanding precisely who will be reviewing the story as it comes together can help prevent problems down the line, such as inadvertently leaving someone out of the process.

This is a good point to have a conference call with a project’s program manager and the PR or communications person driving the story. It’s a chance to familiarize those stakeholders with the news team’s processes and voice, which will be different than a press release or marketing materials. Writers can also send links to, or examples of, the team’s writing to show what kind of content the newsroom produces.

This is also the time for the news team and communications leads to determine who should be interviewed and to zero in on the most important voices.

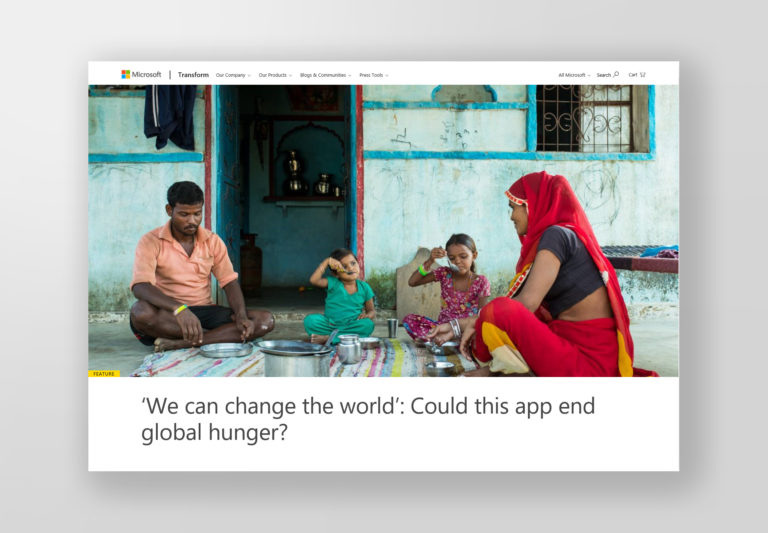

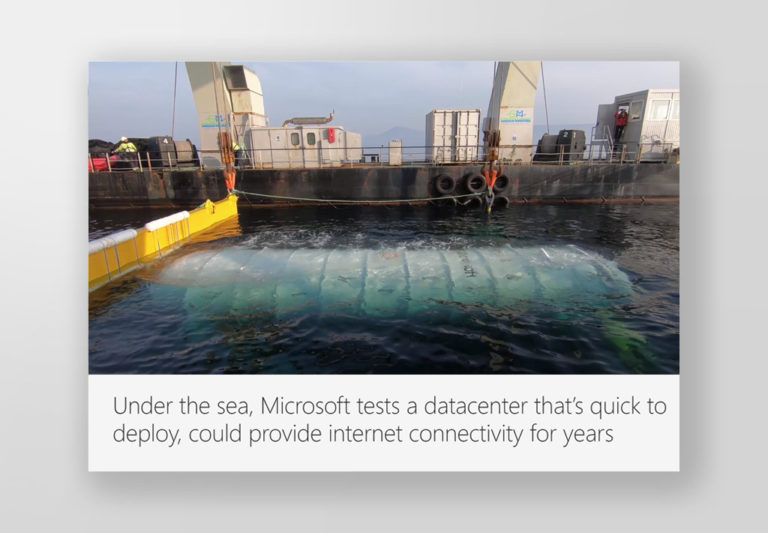

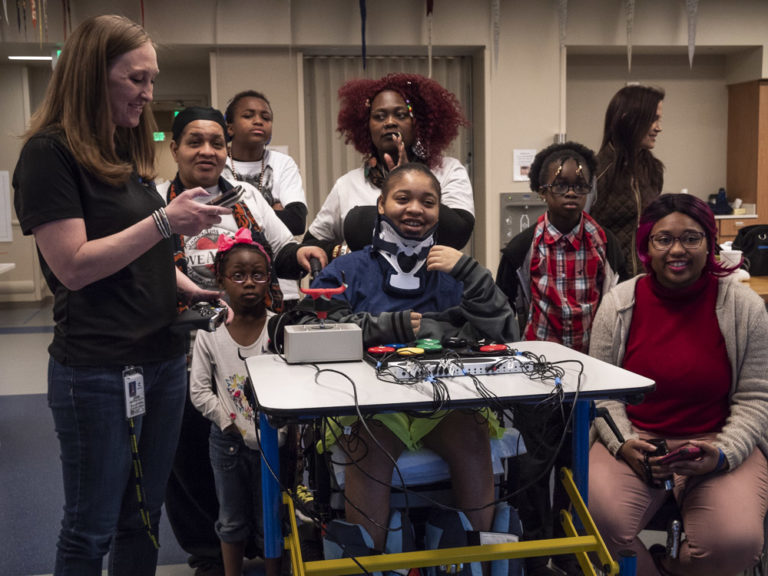

During this call, or as early on as possible, it’s important to convey how vital it is to have strong photography, preferably from a professional photojournalist. If there are any internal politics or sensitivities around the story, those should be confidentially shared with the writer so she can proceed accordingly.

As the reporting process begins, writers ensure that interviewees know that this is an external story (meant for public consumption) but that they will get to review it before it is published. After the initial interviews, it can be helpful for the writer to send the editor, key stakeholders and the communications lead a brief outline of the story.

Once a story is written, an editor carefully reviews and edits it before it is sent to stakeholders for review. This is an opportunity to flag any issues the writer may not be aware of and to ensure that stories are in the best possible shape when stakeholders see them.

The writer, editor or the director determines what process works best for story reviews and asks stakeholders to follow it. It’s most efficient to limit the review to people who are directly knowledgeable about the story and who understand its context and goals; otherwise you risk winding up with uninformed or cursory reviewers working at cross purposes.

To keep the review process moving, writers set specific deadlines for comments and let stakeholders know what level of feedback they are seeking. Typically, this includes spotting factual inaccuracies and ensuring that products and programs are clearly described or articulated.

To eliminate errors or surprises, Microsoft Stories allows anyone who was interviewed to review a story before publication. If there are internal and external stakeholders, a story should typically first be sent to internal stakeholders to lock it down before sending to external stakeholders or sources. Everyone should be on the same page inside the company before it’s shown outside the company.

To avoid churn and confusion, we emphasize that a final version of a story should be final. Edits after a final document has been sent creates confusion, version-control issues and needless extra work. Avoiding that vexation is a good reason to have everyone work from the same document.