“We are redefining the meaning of beauty to help kids grow up being comfortable in their own skin.”

Johannesburg doll maker Khulile Vilakazi-Ofosu takes on the lack of representation in children’s toys by creating dolls that reflect, affirm, and engender pride in being African.

“Mommy, please make my hair flowy.”

Khulile Vilakazi-Ofosu had just picked up her daughter from preschool in Johannesburg, South Africa. When Isha made the request, Khulile put down her keys and the child’s backpack and squatted down to make eye contact.

“What do you mean, love-love?” Khulile asked.

Isha, who was only 3 years old at the time, explained. Her friends at school could flick their hair; it was fine, flowy, and long.

Isha’s hair was not like that. “It was the thick, tightly curled, beautiful Afro hair that didn’t do all the things her friends’ hair could do,” Khulile said.

Mommy, please make my hair flowy.

Khulile felt her heart sink.

“I thought, my goodness, she’s so young, and she’s already wishing for something that she is not.”

Painful memories from her own childhood pricked Khulile as they surfaced. She couldn’t recall a time when she was celebrated, hugged, or told she was beautiful. She also remembered her old nickname, “Sdudla” which means “fatty,” a term of endearment in Zulu, Khulile’s native language. This nickname never sat right with her. She grew up thinking she was ugly because wherever she looked—in magazines, on TV, and in movies in the 1980s—there was almost no one who looked like she did; she saw only blue-eyed, blonde, fair-skinned, super thin women. No one assured her otherwise.

Years later, when she decided to have a child of her own, Khulile devoted herself to celebrating her daughter’s victories and being there for her challenges. And here it was—the moment where that resolve was put to the test.

That fateful conversation kickstarted Sibahle Collection, a line of dolls crafted to better represent the diversity of children in South Africa and all over the world.

*****

Inside the gleaming white storefront, Khulile picked up a doll to show a customer who wandered in off the street in Ferndale, a suburb of Johannesburg, where the shop is located.

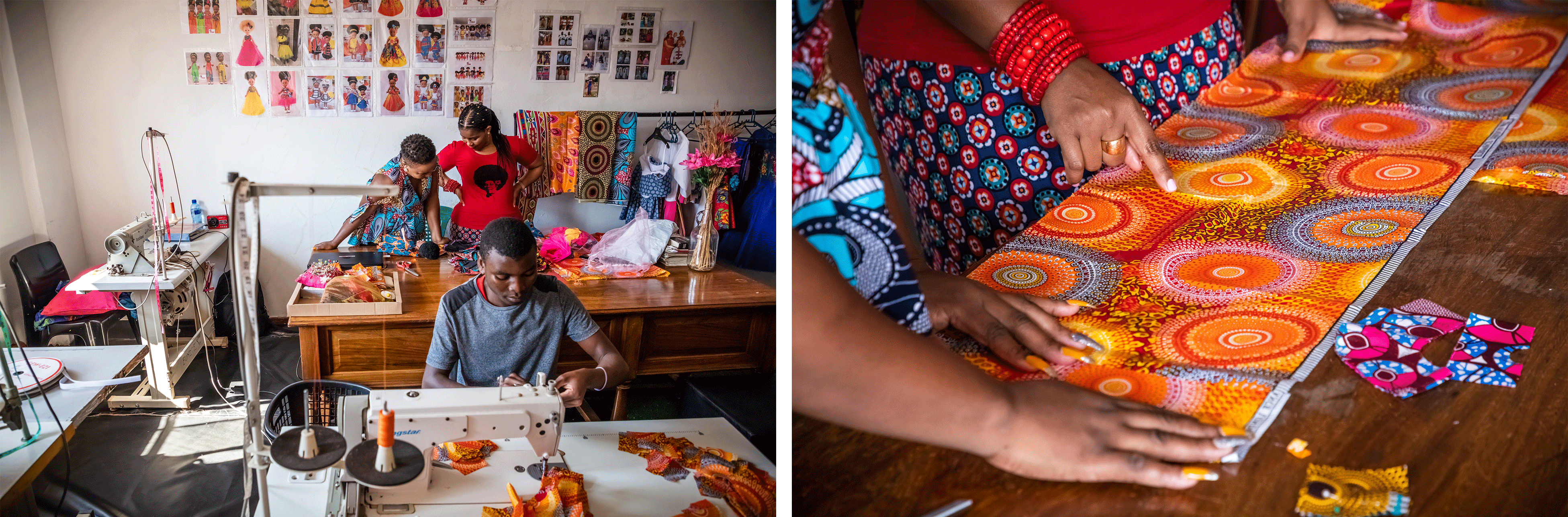

Sibahle Collection, which started in Khulile’s garage in 2017, quickly grew into this shop, where she transferred the business in 2018.

The doll, dressed in a bright orange and yellow print with small black polka dots, had vitiligo, a long-term condition in which skin loses its pigment cells. The woman touched the doll with fascination, looking up at Khulile with soft, sad eyes.

“Do you know what this would have done for my self-esteem, if I had grown up with a doll that looked like me?” she said to Khulile.

*****

Though the mission of Sibahle Collection is for every child to grow up aware of the beautiful and rich diversity that the world has to offer, the beginning of Khulile’s story didn’t start with every child. It didn’t even start entirely with her own child.

It started when Khulile herself was a child.

Every morning in the township of Newcastle, several miles south of Johannesburg, Khulile would wake at dawn. She’d stoke the coal fire to warm up the house and place a concrete brick into the fire. Then, she’d wrap the brick in newspaper and hold it close to her body to keep her warm in the bitterly cold Newcastle winter, while she walked to school.

One morning, as she stood outside holding her hot brick, she turned around to take in the rows and rows of impoverished homes in the low-income housing where she lived. Smoke poured out of the roofs, each warmed by a coal fire just like hers. Suddenly, Khulile caught the faint whisper of fate on the wind, as sure and silent as the gentle snow falling around her.

“This isn’t your destiny.”

At that moment, she knew it. She wanted something other than what life had handed her. And she would go get it.

*****

Khulile was raised by her great grandmother, and then her grandmother when her great grandmother passed away, because in her culture a child who was born out of wedlock could not go live with her mother’s new family if the mother married.

“My mom was about to marry my stepdad. She had no choice but to leave me behind, as dictated by our culture” Khulile said, shaking her head in disapproval.

She pushed herself hard in school—harder than anyone else she saw. Education became the vehicle she’d use to usher in her bright future.

She went away to boarding school, then on to college, and then into her career in finance. She traveled the world and learned how to speak seven of the eleven South African official languages. Eventually, she met her spouse, a man from Ghana, got married and soon they had their first child. But during her pregnancy, Khulile began to lose her hair.

“I’d always had very thick, beautiful Afro hair. It was my pride. But I began to shed the hair, and six months after I gave birth to my daughter, I lost all my hair. I was bald.”

Khulile had just given birth, and the loss of her hair extended her intense emotions into a miserable 18 months of depression. After work every day when the baby was sleeping, Khulile would search the internet and research desperately, seeking out artificial hair that would look and feel like that of an African woman.

Her search led her to her future business partner, Caroline Hlahla.

Caroline, who lives in London, had started selling natural, Afro-centric looking hair that she sourced from an Indian manufacturer who repurposed it. Khulile found her on Instagram and bought some right away. She loved it; it looked exactly like her own hair. But there was one problem. The clips for attaching the artificial hair to her head required at least a little bit of natural hair. At that point, Khulile had none.

That’s when she taught herself how to make a wig, by watching YouTube tutorials.

She loved the result and reached out to Caroline to tell her. Caroline knew Khulile was on to something, and they decided to launch a wig company together, bringing extensions, clip-ins, and wigs to South Africa.

She loved the result and reached out to Caroline to tell her. Caroline knew Khulile was on to something, and they decided to launch a wig company together, bringing extensions, clip-ins, and wigs to South Africa.

*****

Two years after launching the wig company, after the fateful chat with Isha after school, Khulile decided that she would find a doll for her daughter that celebrates how Isha looks. It wasn’t as easy as she assumed.

“It’s not that there haven’t been Black dolls in the market,” she explained. “But those were white dolls with European features, painted Black. I found no dolls with flatter noses or more pronounced foreheads like my daughter’s.”

Armed with her new-found entrepreneurial confidence, Khulile and her partner Caroline decided to make their own dolls.

We had learned how to bring synthetic hair to life for women, so why not on a doll—a doll that kids could play with and use to learn how to take care of their own hair.

The adventure to find a doll manufacturer began. The search went global.

“First, the manufacturers were not willing to make a Black doll. They told us straight out, ‘Black dolls are ugly. Black dolls don’t sell. But we can give you a Barbie and paint it Black.’”

That wasn’t the vision that Khulile had at all. “I’m not talking badly about any brand; Barbie is what I grew up with. But they are made with these sharp noses, this unrealistic body structure. That’s not typically what Black kids look like.”

Eventually the search lead them to a European manufacturer that understood what Sibahle Collection really stood for—to be a voice for those who have been marginalized, for those kids who have been ignored by the doll manufacturers or the toy industry.

“We are redefining the meaning of beauty. We’re teaching kids that there’s beauty in diversity,” she said, “to help our kids to grow up being comfortable in their own skin, whoever they are.”

The word Sibahle means “we are beautiful” in Zulu, Khulile’s tribe. And in February 2017, the brand released its first doll and sold all 300 almost immediately. Since then, it has sold dolls that have albinism, dolls from South Africa’s various tribes, dolls that have vitiligo, and dolls that represent Indian children. There are plans to design dolls that have cleft palates and alopecia brought on by chemotherapy.

“The bottom line for us is that no child deserves to feel less than. So when a child is getting chemo, she’s got something that she can look at and say, ‘You know what, the fact that I don’t have hair doesn’t make me any less worthy, any less beautiful.’”

The bottom line for us is that no child deserves to feel less than.

The company has also launched merchandise like storybooks, backpacks, puzzles, rainboots, and party packs for kids to celebrate their birthdays. They’ve even been approached about doing a cartoon miniseries.

While it’s all very exciting to Khulile, who juggles family, her professional life at Microsoft, and the Sibahle Collection, her load is no walk in the park.

“I am privileged to work for Microsoft, especially for the team that I work for. It’s a very empowering environment that encourages us to pursue our passions and help us create a positive impact in the communities we live within and still be able to be productive employees at work.”

Despite all the hats she wears—or perhaps, because of it—she is unwavering in the message she has for all children: that every child deserves to see themselves in the toys that they play with and deserves to know that they are beautiful just the way they are.

“Whoever you are, you are special in your own right.”

*****

When Isha first saw the dolls that her mom created, she could hardly believe it. “Mommy! Is this me?” she asked excitedly.

“It’s not you exactly, baby. It’s a doll that looks like you,” Khulile said.

“She’s sooooooooo beautiful,” Isha cooed, squeezing the doll to her chest, running off to play, fidgeting with the dress, and braiding the doll’s curly hair.

Hair that looked just like her own.

*****

Photography by Rodrigo De Medeiros; Videography by Rodrigo De Medeiros and Steven Heller; Additional reporting by Amanda Finney.