Chasing peak sugar: India’s sugar cane farmers use AI to predict weather, fight pests and optimize harvests

Read this story in Hindi & Marathi

Nimbut, Maharashtra, INDIA – “Ready?” Suresh Jagtap asks, then turns and disappears into a field of tall sugar canes.

Inside is a world of dappled green. The 65-year-old farmer bats rustling leaves aside, clearing a swift path to a thin metal structure rising above.

His family has been farming in the area for generations – vegetables, fruit and, more recently, sugar cane. Over the years, climate change has made the weather more unpredictable and extreme, and raised the risk of pests and disease.

Recently, Jagtap turned to AI for help, aided by scientists at the nearby Agricultural Development Trust (ADT) of Baramati and using Microsoft AI technology.

The tall metal structure is a weather station. At the top are wind, rain, solar, temperature and humidity gauges. At the bottom, sensors in the soil measure moisture, pH and electrical conductivity as well as nutrients like potassium and nitrogen. The data is combined with satellite and drone imagery as well as historical data and analyzed to generate simple daily alerts via a mobile app: Water more. Spray fertilizer. Scout for pests. A satellite map pinpoints exactly where each action is needed.

The goal is to do just the right thing at the right time to optimize growing conditions and claim the ultimate prize: a harvest when sucrose content in the cane is at its peak.

Since planting this one-acre test plot on his four-acre farm six months ago, Jagtap and his family have been following the guidance religiously. Harvest won’t be till November 2025, but already they see the difference.

“The growth is good,” Jagtap said. “The leaves are greener and the height is more uniform.”

“Seeing is believing”

India is the world’s biggest producer of sugar cane but much of it comes from small farms like Jagtap’s in Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh in the north. For small farmers, drought, floods, pests and disease can wipe out entire harvests and push farmers into debt and even to suicide.

ADT Baramati was set up in the 1970s to help farmers in the drought-prone region adopt modern farming methods. Today, it has an active outreach field force and its researchers collaborate with institutions around the world. Its field agronomists have introduced local farmers to – among many other things – drip irrigation, which uses far less water than the traditional flooding of fields, soil-less farming, modern grafting methods and artificial insemination with foreign bulls and local cows to raise milk yields.

Some 1.6 million local farmers are beneficiaries of ADT Baramati. The Trust hosts an annual farmers’ festival called Krushik at its 150-acre campus where new techniques are introduced, attended by more than 200,000 farmers from around India.

“Seeing is believing is the philosophy of farmers,” said Pratap Pawar, a trustee at ADT Baramati.

It was at the January 2024 farmers’ festival that ADT Baramati unveiled its AI project – about a dozen crops from sugar cane to tomato to okra, all grown with insights harnessed by AI. They called it the “Farm of the Future.”

The sugar cane test plot had yielded stalks that were taller and thicker – weighing 30 to 40 percent more at harvest – and yielding 20 percent more sucrose. The plot required less water and fertilizer, and the entire crop cycle was shorter – 12 instead of 18 months.

“We showed water-related data, weather data, nutrients, pH of the soil,” said Dr. Yogesh Phatake, a microbiologist working on the project. “We got a very exciting response.”

Some 20,000 farmers signed up. From those, 1,000 were chosen for the first trial, focused on sugar cane. An initial cohort of 200 began planting in mid-2024.

The sugar cane test plot yielded stalks that were taller and thicker – weighing 30 to 40 percent more at harvest – with 20 percent more sucrose.

Averting an AI divide

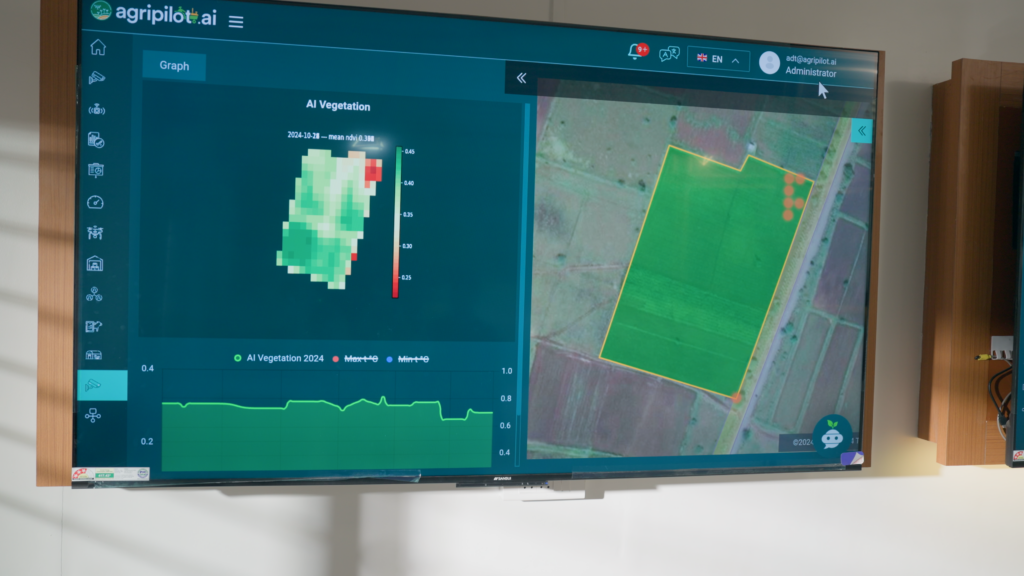

The technology brings in weather, soil and other data from satellites as well as farm sensors onto a Microsoft data platform called Azure Data Manager for Agriculture (previously called FarmBeats), so farmers can see precisely what’s happening at their farm with a few clicks.

Project FarmVibes.ai, an open-source research project from Microsoft Research, builds on FarmBeats to analyze the data, along with historical crop data, to provide insights – covering everything from whether crops are getting enough water to whether a farm has a pest infestation, what kind and how to get rid of it.

Generative AI takes it a step further. Microsoft Azure OpenAI Service turns technical details into simple daily actions for the farmer – fertilize in areas pinpointed by satellite data, for example, or scout for pests, all delivered through a mobile app in English, Hindi and the local Marathi languages. It also creates a crop lifecycle plan for farmers in simple language, so they know exactly what to do next, taking the guesswork out of farming.

The mobile app is called Agripilot.ai, customized for ADT Baramati by Microsoft partner Click2Cloud.