Since farmers began digging up ancient bone fragments in the fields around the Yellow River in eastern China over 100 years ago, researchers have been poring over the mysterious script found on them.

The script on the “oracle bones,” so called because they were used to try to divine the future, is the earliest known form of Chinese writing, dating back 3,000 years. But their study has been challenging: the bones are fragile and fragmented, copies of the script made by ink rubbings can be blurry or incomplete and collections are scattered in national museums and private collections in China and around the world.

Now researchers in Beijing are using AI to fast-track the basic but necessary work of comparing each script sample with thousands of others in databases. This work paves the way for researchers to decipher them and shed light on everything from the daily concerns of people in ancient times to how Chinese writing first developed.

“This is a great example of human-machine collaboration,” said Bofeng Mo, a professor from the Center for Oracle Bone Studies at Capital Normal University, who worked on the project with Zhirong Wu, a senior researcher at Microsoft Research Asia.

Oracle bone inscriptions have been recognized by UNESCO’s International Memory of the World Register as a valuable record of the Shang people from 1400 B.C. to 1100 B.C., in addition to being the earliest evidence of a Chinese writing system. In China, every kid learns about the oracle bones in school.

Most of the bones were excavated around Anyang City in Henan Province, about 500 kilometers (about 310 miles) southwest of Beijing. They were usually the scapula, or shoulder blades, of oxen or the belly shells of turtles – both of which offer a flat surface for the script. During the Shang Dynasty, a bronze-age civilization, someone would heat the bones until they cracked. The pattern of the cracks would offer guidance on matters around praying, royal and military affairs, the weather, harvests and so on.

Since 1899, about 150,000 pieces have been unearthed and are now housed in more than 100 institutes around the world, according to experts behind the UNESCO nomination. The biggest collections are in the National Library of China, the Palace Museum and other Chinese institutions though oracle bones collections are found as far away as the Royal Scottish Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada.

The markings have both pictograph and text elements. With no equivalent of a Rosetta Stone as a guide, scientists have only deciphered about 1,000 of the approximately 4,000 characters identified.

Up until now script study has been painstakingly laborious. The earliest copies of oracle bone script were made by Chinese ink rubbings and, more recently, photographs and 3D imaging technology. Researchers had to manually compare each image to find duplicates or overlaps, with the goal of stitching together fragments – like a jigsaw puzzle – into a more complete whole for study.

“Since a piece of oracle bone may have been recorded several times with different levels of clarity and integrity, a lot of work is need to relate, compare and interpret them,” Yubin Jiang, a researcher at the Research Center for Unearthed Documents and Ancient Characters at Fudan University, told Microsoft. “In the past, this burden fell solely on the shoulders of scholars with rich experience and sharp memory, but their research only led to random findings.”

“Diviner has managed to complete wide-ranging duplication detection in a highly efficient, fruitful and exciting way,” he added.

Wu, the researcher at Microsoft, focuses on the nascent field of self-supervised learning, a type of machine learning that does not rely on people to do manual labeling of data. He approached Mo about a year ago after hearing that the professor was experimenting with AI to study script. At the time, Mo was using off-the-shelf image recognition software, which only allowed a few images to be uploaded each time and required a user to pick one as a reference image.

“We developed the technology to train the Diviner model from scratch,” said Wu.

Wu said he and one other team member took eight to nine months to build the model. In November 2022, in the space of one week, the Diviner Project compared 181,134 pieces of inscription rubbings across 100 databases. It not only reproduced tens of thousands of previously identified duplicates found by people but also found more than 300 new pairs.

After Wu and Mo shared the results on the website of the Pre-Qin Research Office at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, which has its own substantial collection of oracle bones, researchers at other institutions have reached out to them for help, said Wu. The project was also featured in a special oracle bones episode on national broadcaster CCTV on January 2, 2023.

This is just the first step.

“The current project is to clean the data and recover the data to the original form by joining small fragments to the original big one,” said Wu. “With this, we hope we can move on to the final challenge – deciphering the meaning of these characters.”

Those findings could have implications for different fields.

“To archaeologists, they are the cultural remains of humans. To historians, they are the historical material of the Shang Dynasty. To linguists, they are the earliest systemic Chinese characters,” said Mo. Moreover, “records of solar eclipses, lunar eclipses and meteor showers found in oracle bone inscriptions can be merged with astronomy.”

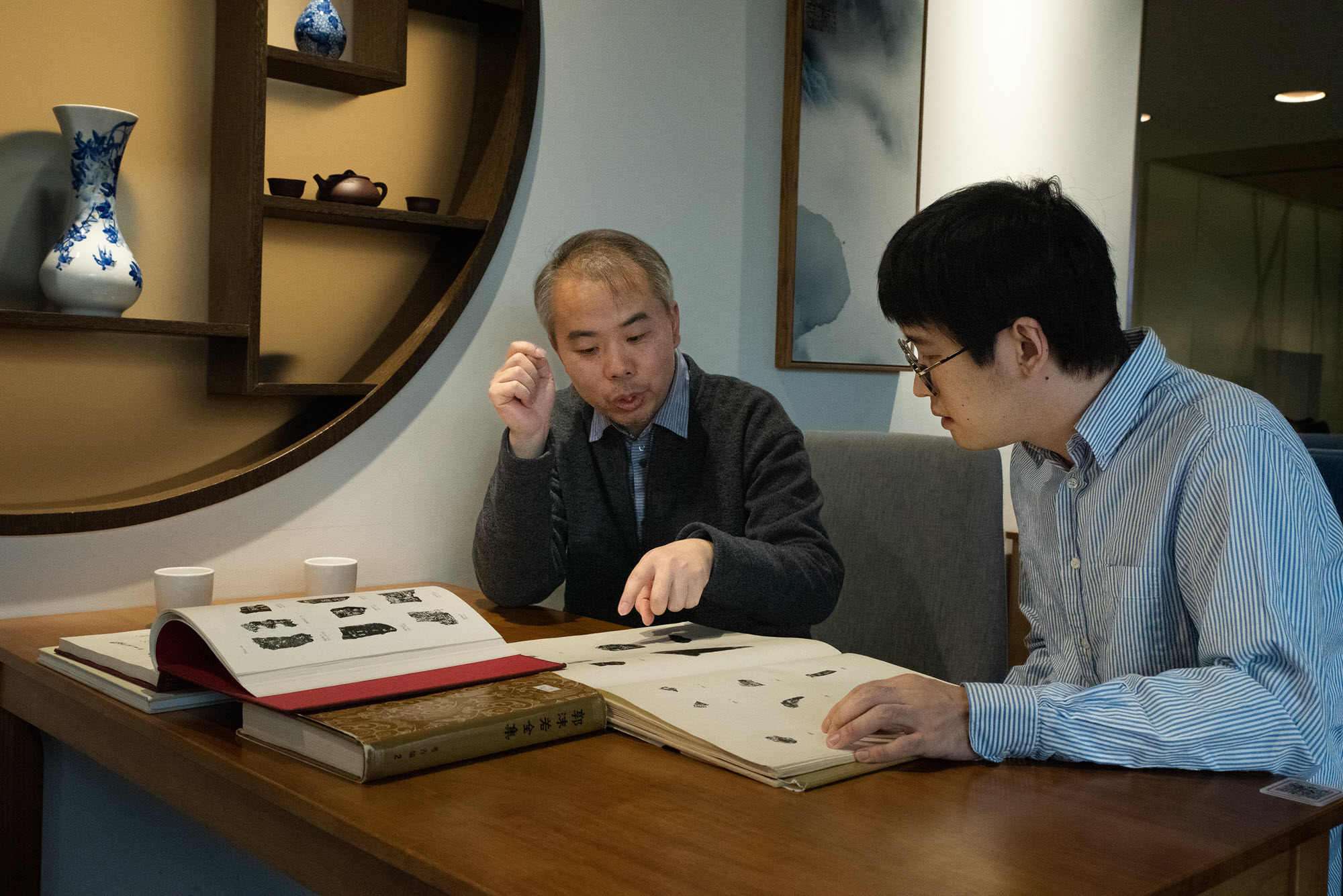

Top image: Zhirong Wu of Microsoft Research Asia uses AI to study ancient Chinese script on oracle bones. Photo by Gilles Sabrie for Microsoft.