Uniting the world in the classroom: How AI breaks barriers in a Belgian school

ANTWERP, Belgium – Under a cold predawn rain, a frenzy of children wrapped in parkas and winter scarves ran, climbed, shrieked and whispered in tight clusters across the courtyard.

If you listened carefully, you could hear some speaking Dutch, but also Pashto, Arabic, Spanish and Ukrainian. At this school known as De Wereldreiziger, or the World Traveler, there are 70 languages spoken by the 425 students, many coming from families fleeing war or economic distress.

Different languages, different levels of education at home and dramatically different lives outside of school – enormous challenges for educators. How to help a kid who lost his home to bombs in Ukraine or Gaza level up with a child from a middle-class Flemish home?

The answer is a combination of openness of spirit – the principal of the school makes a point of saying the diversity here is a “richness and an opportunity for learning” – and a willingness to try new things.

Using a variety of tools from Microsoft, the school is finding ways to let each teacher reach more students individually. Those tools include AI-powered apps to help build reading and speaking skills and Surface laptops for every child beginning in third grade.

Charlie Todts, a teacher and liaison at the school, was in the courtyard observing the chaos calmly, greeting parents and students as the school day began.

A native of Antwerp, she said she believes in the school’s approach. Her oldest daughter, who is 7, was there in the courtyard, too, and her youngest, 3, at the World Traveler preschool just down the street.

“My oldest can say good morning in like eight languages,” said Todts. “I can’t do that. I like that we have the whole world here.”

In her view, the tools provided by Microsoft are indispensable when students come from such different backgrounds. “I know that when I teach without laptops or these new apps, it’s really difficult to reach 20 kids each on his level,” she said. “I can’t do it. I only have two hands, and with these tools, I can reach more kids.”

Recognition for AI excellence

On the second floor of the school in the teacher’s lounge, Principal Jef Groffen arrived from his bike commute in wet rain gear. He has led the embrace of technology at the World Traveler school since his tenure as principal began seven years ago. Groffen’s success in improving reading results at the school earned it the Special Belgian Award for AI in Education as the best project in the country.

Groffen sat down to talk about the school and its philosophy.

Because of the World Traveler school’s location – in the center of Antwerp just a short walk from the main train station – its population is truly global. But to thrive in this part of Belgium, Flanders, one must speak Flemish Dutch. Flemish Dutch is spoken by about 6.5 million people – more than half the population of Belgium. The other two official languages of Belgium are French and German.

He pulled up a PowerPoint presentation on his laptop that showed some key measures: More than 70 percent of the students do not speak Dutch at home. And almost 60 percent of the families have a mother who doesn’t have a high school degree.

That, Groffen said, is a key indicator of how the students will perform. “Children who, for one reason or another, grow up in a more difficult situation are exponentially more likely to leave education unqualified,” he says. “A successful school is a school that successfully combats that fact.”

“We are professionals. We know how to teach them, but we just don’t have enough people to fix this,” he said. “Technology is the only way, I think, to address the difference between children in one classroom here.

“If you work with Microsoft Teams very well, it feels like you have 25 assistants in your class,” he said. “Every child has his own assistant, and it is helping them develop quickly. The possibilities are endless.”

Making the ability to read a priority

In 2019, the school started giving every student their own Surface laptop beginning in the third grade. Students can access lesson plans and homework through Teams; teachers and administrators use Teams and Sharepoint to organize their work, conduct meetings and share evaluations.

The ability to read technically is necessary before being able to read comprehensively, Groffen said. He explained that technical reading involves the ability to decode and convert letters and words into their corresponding sounds, allowing the reader to understand and pronounce the text accurately. And that is key to success in everything else that follows in school, he said.

The two tools that have been key in helping non-Dutch-speaking students catch up with their peers are Microsoft Reading Progress and Microsoft Immersive Reader. They both operate on the Teams platform.

Reading Progress makes a video of the child reading; AI analyzes the exercise in real-time, gathering data on reading speed, mistakes and pronunciation. Then it gives the student feedback so that the student can see and hear where they had difficulties, and practice to improve.

“Reading Progress is the most sophisticated tool we use,” Groffen said. “It started with two or three teachers who tested it on with a few children. We booked lots of success. For some students it was taking three weeks to make the same progress that before took six months. We can prove it, because we are a school that measures everything we do.”

Groffen said he and the other teachers at the school believe that it’s better to use the same texts for all students regardless of their level in Dutch, using instant translation so that non-Dutch speakers can participate fully in real time.

In the past, assigning easier work to non-Dutch-speaking students or holding them back a grade have proven to be losing strategies, he said. “We now try to offer all students the same complex, rich texts and keep everyone on the same high level,” he said. “And one of these ways is the Immersive Reader. It is magic.”

With the Immersive Reader, students can read a text in their own language and then in Dutch. They can click on key words and see illustrations that show their meanings. It’s even able to translate spoken language in real time, meaning students can, in effect, have instant subtitles of a teacher’s instructions in their own language. It also has tools to help dyslexic students, for example.

Using this tool, “many more children increase their insight into texts and can follow the standard reading comprehension lesson in Dutch for their age,” Groffen said.

Making equal access to education a global priority

Kris Vande Moortel is a Microsoft education advisor in Belgium who worked closely with Jef Groffen and the World Traveler School to test the efficacy of reading apps, which are provided to schools in Belgium and elsewhere for free.

Vande Moortel said that about 600 teachers and almost 4,000 students are using reading apps in Flanders now. Beginning next year, the use of the apps will be greatly expanded through a project with one of the government school networks of primary schools, he said.

Matt Jubelirer, Senior Director for Microsoft Education Marketing, said the example of the World Traveler School is emblematic of Microsoft’s commitment to education.

“The school’s mission is to prepare the next generation,” he said. “Our approach at Microsoft is really to focus on how we can help enable equitable education across the world.”

He said Microsoft had programs to assist in K-12 and higher education in most, if not all, of the countries where it operates.

In Belgium, Vande Moortel said setting high standards is one key to the World Traveler School’s record of success. He was a teacher himself for more than 20 years, and said he admires the philosophy espoused by Groffen.

“Even with the challenges in that school, with 70 different languages and half the kids having a refugee background, he says my students have the highest potential, that they are the future, and I think that’s quite powerful.”

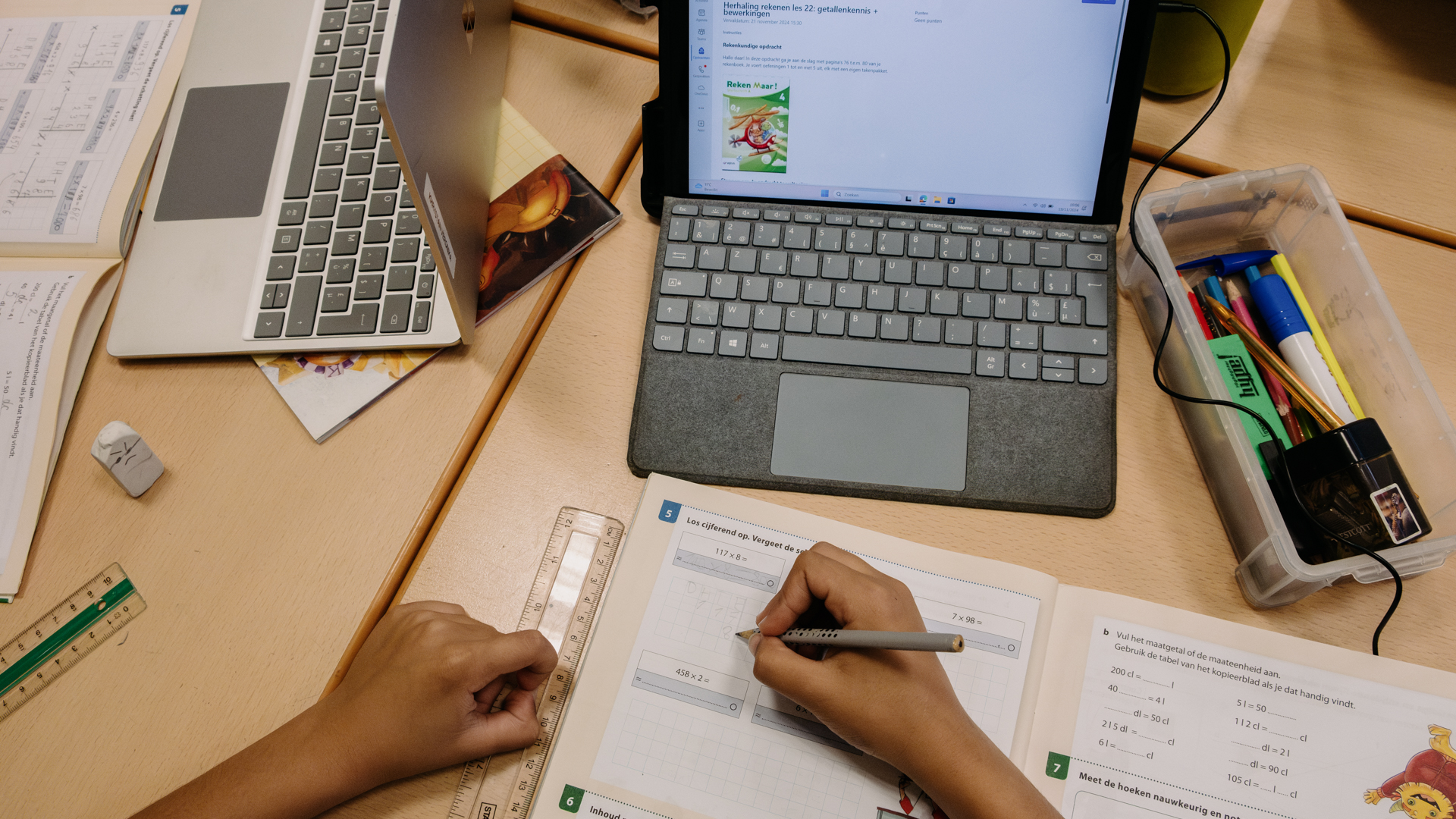

Dieter Eyzermans is a fourth-grade teacher (ages 8-9), one of the school’s Microsoft Innovative Education Experts (“MIEEs”), who has taken extra training in the technology in use and who helps other teachers learn how to use it was monitoring his class of 25 pupils as they worked on assignments during class. Some were practicing exercises about how to tell time and others were working on math or reading.

At his desk at the front of the class, he demonstrated how it was possible to follow students’ progress in solving math problems as well as seeing which tasks they had completed, and which tasks they were still struggling with. He said the benefits of the technology were twofold; it has “massively” reduced his workload, while at the same time allowed him to focus more individual attention on students.

“I can easily see which children are done or which are still working,” he said. “I can put tasks for the children at their level, individually. Now I just can select tasks: this one is for you, this one is for you. Secondly, I can check more easily. I can give feedback individually to the children.”

While he is an advocate for technology in the classroom and has seen its benefits firsthand, he knows the human touch is essential. “I use AI to help me write comments in my report cards, for example, but I always use my own mind. I check to make sure it’s something I would say, that it’s accurate.”

“There are a lot of teachers who are scared of technology. They think it’s not for me, I can’t work with it, but I encourage them to just try it,” he said. “Don’t be scared of it, but embrace it with a clear mind. Don’t trust it for 100%, you’re still a human being, but let technology support you in your daily life and daily work.”

Todts said that she and her husband, who is also a native of Antwerp, had the choice of where to send their children to school. They decided on the World Traveler school and haven’t regretted it.

She said they had some concern that their children might find it harder to find friends, because for most of the kids, Dutch is the second, third or even fourth spoken language they’ve learned. But Dutch is also the shared language on the playground.

“Fortunately, this was no longer a concern after a few days,” she said. “Children can communicate with each other on so many different levels that adults sometimes have no idea about. It’s fantastic!”

Their daughters have friends from all over the world, they’re exposed to different foods, different styles of dress and different cultures every day.

“When we go on a holiday or we are away, then she knows the world, because the world is in our school.”

Header image: Two fourth-grade students are working on a PowerPoint presentation about animals at the World Traveler School in Antwerp. Photo by Chris Welsch for Microsoft.