Spend an evening on the steps of one of Beirut’s iconic public staircases. What do you hear? The footfalls and delighted shrieks of children chasing one another. Their parents chattering about the day’s dramas over clinking glasses, forks scraping up the last bits of hummus from a dozen mezze platters at a nearby restaurant. Shop doors sliding down and locking with a clank.

You hear street life, the vitality of the city, in all its noisy glory.

Perched on a hillside overlooking the shores of the glittering Mediterranean, Beirut is peppered with iconic staircases that connect the city’s neighborhoods, but they’re more than a way to get from here to there. They’re vital meeting places, the lifeblood of a community.

On an idyllic summer day in 2020 these sounds of life were silenced by a blast so large it was almost incomprehensible. Doors blown out. Windows shattered. Cars crushed like soda cans. Streets blanketed in a thick gray ash. Devastation for 20 kilometers.

The stairs themselves weren‘t that damaged, but they were once one of the most socially active areas in Beirut. After the blast, everyone left, and that‘s not something you see any more.

The city’s port had been rocked by a massive blast – the largest non-nuclear explosion in recorded history—caused by the accidental detonation of 2,700 tons of improperly stored ammonium nitrate. 217 deaths. 7,000 injured. 300,000 displaced.

Residents staggered out of their homes to find their city in ruins. Ever since, the staircases, once hubs for strolling lovers, picnickers, tea sippers and life livers were now just…steps.

How do you coax life back into a public space? How do you make it safe and inviting again for families and businesses? You give people the tools to tell you what the space needs, and then you build it, block by block.

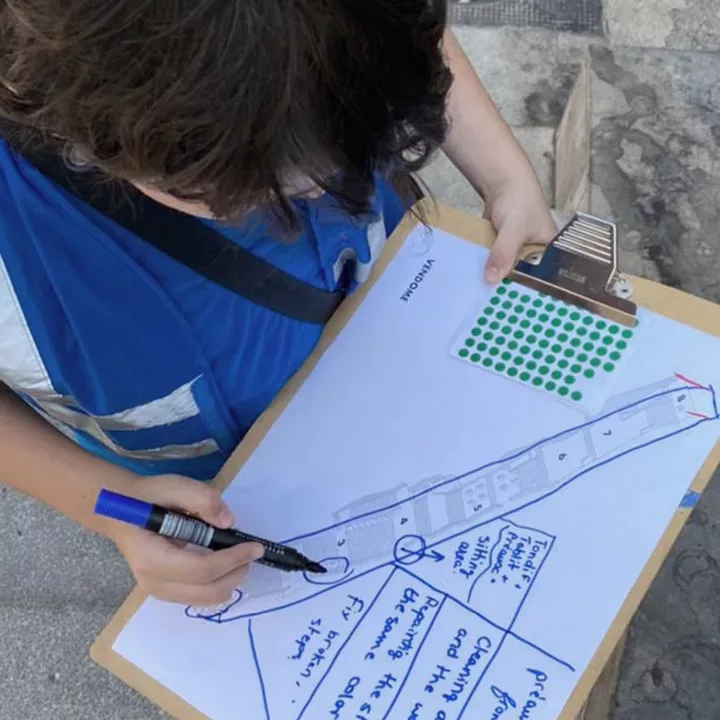

But what tools, exactly? How can you give the people—even kids—a seat at the drafting table? The answer, the world’s most popular video game: Minecraft.

This is the story of how game developers partnered with urban planners to build a radical new approach to urban development—one that would span 48 countries and change how the UN itself thinks about designing public spaces.

Building blocks

In 2011, the city of Stockholm began updating some of its crumbling public affordable housing. The dour concrete tower blocks had excellent floor plans but were designed with minimal outdoor space and amenities. They were unappealing to everyone but people who couldn‘t afford to live anywhere else.

The city wanted to renovate this housing, but there was just one problem: the residents had an intimate understanding about what would be needed to improve the spaces, but there was no easy way for them to articulate it in a way that architects could then translate into blueprints. This was especially true for younger residents, who are the least likely to attend community planning meetings.

You could teach people to use more refined architecture tools, but it would be much harder. This gave us a way to hear how people wanted to use the space, without them also having to choose where the doorknobs go.

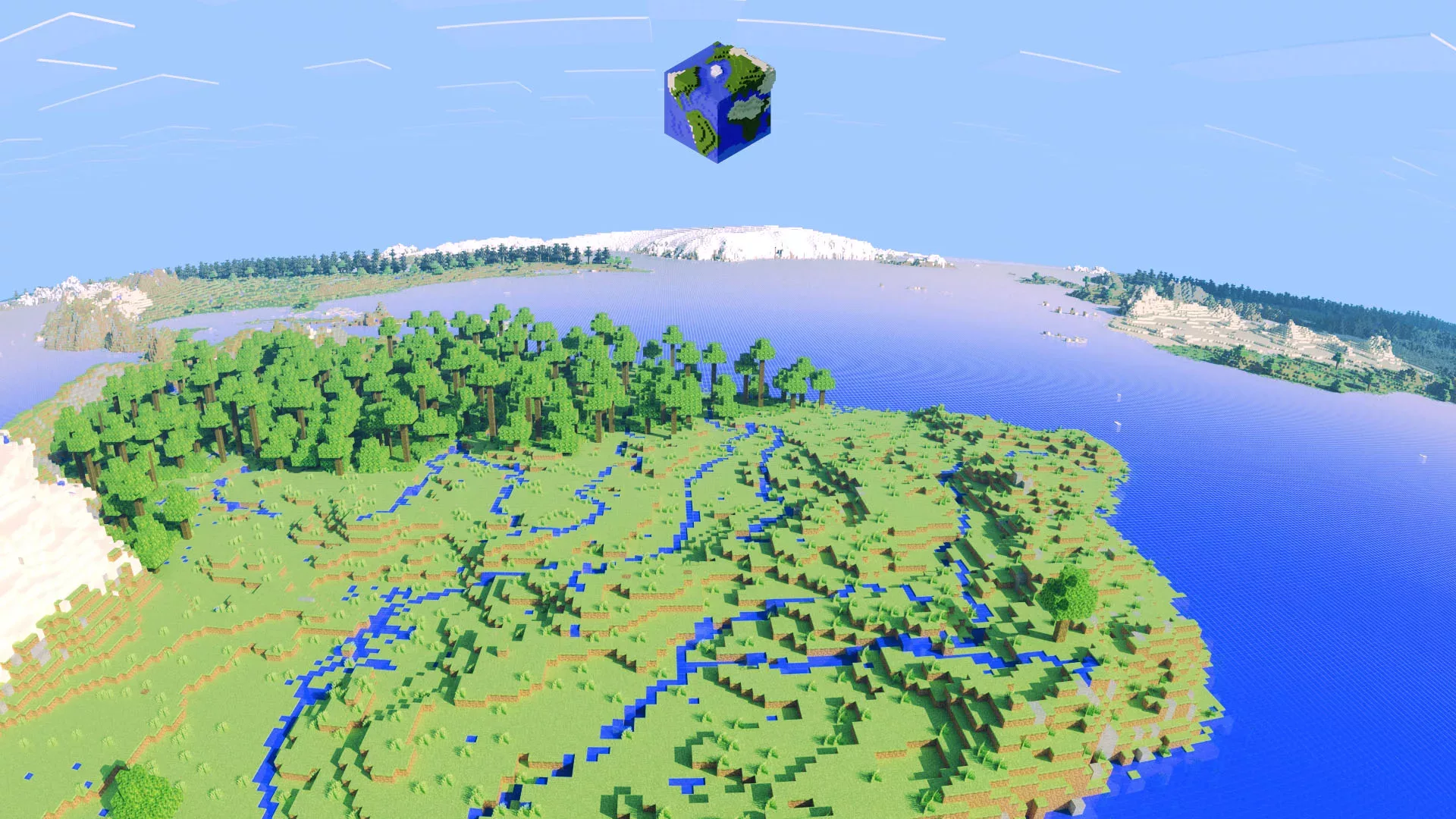

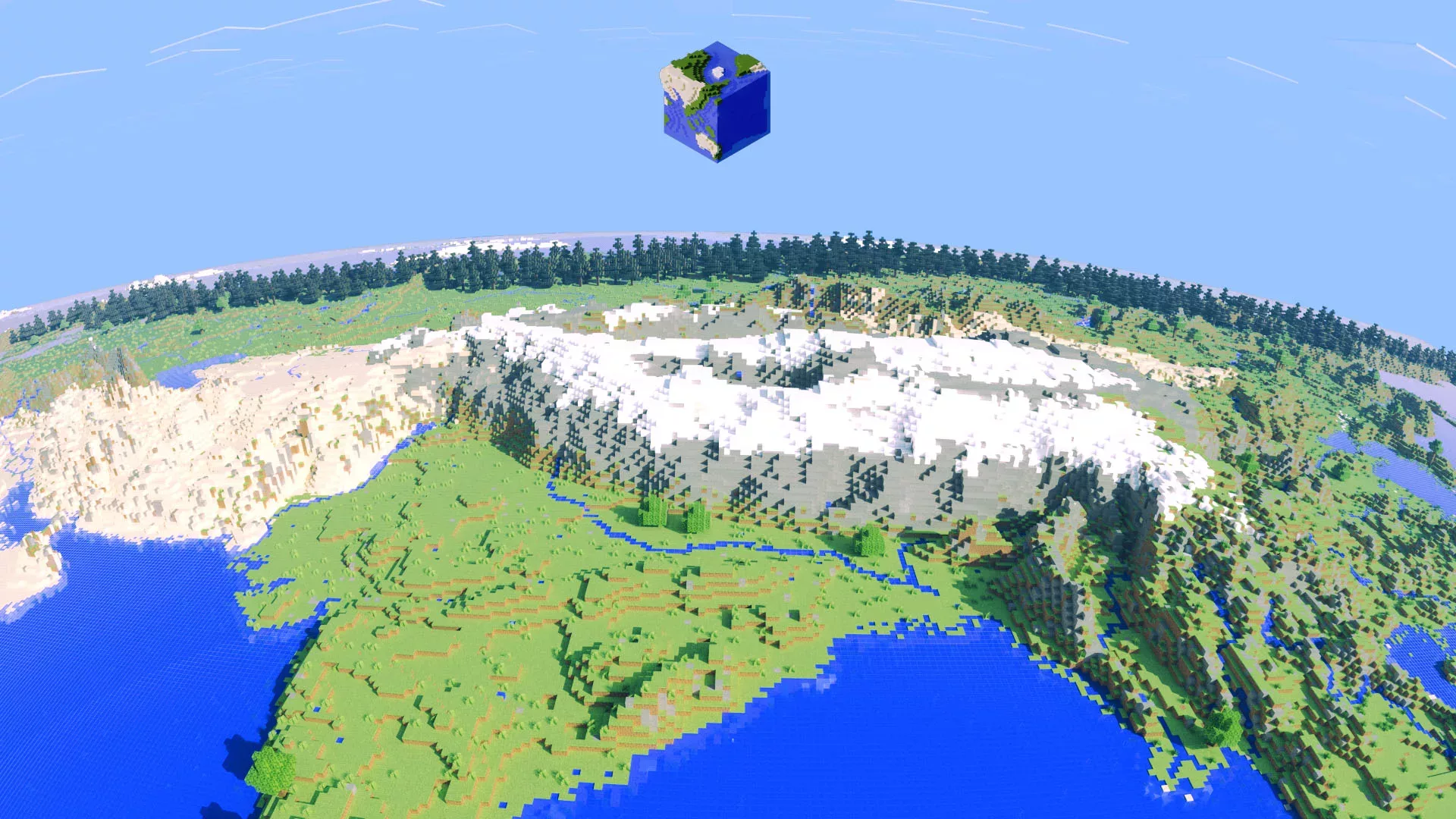

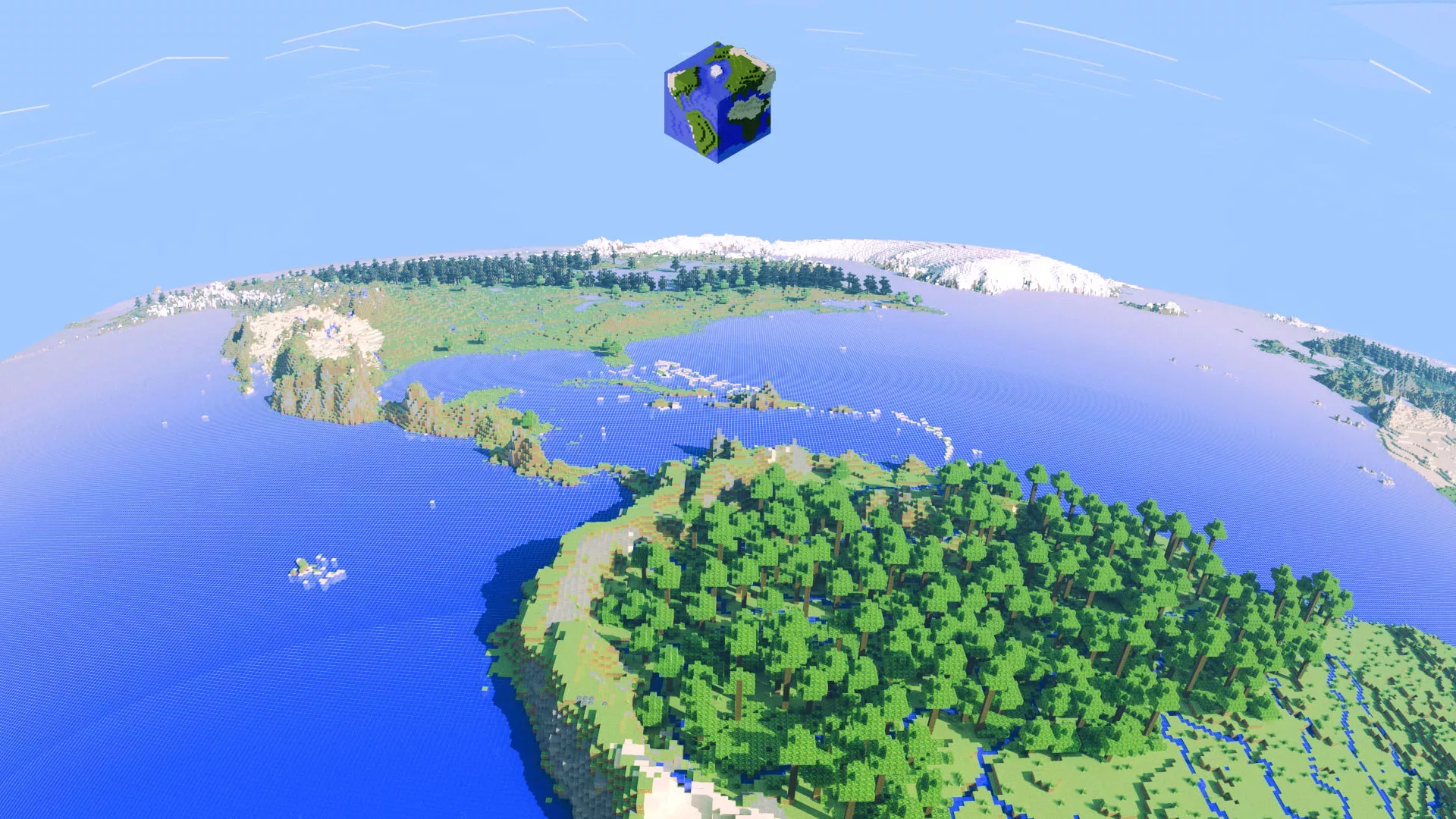

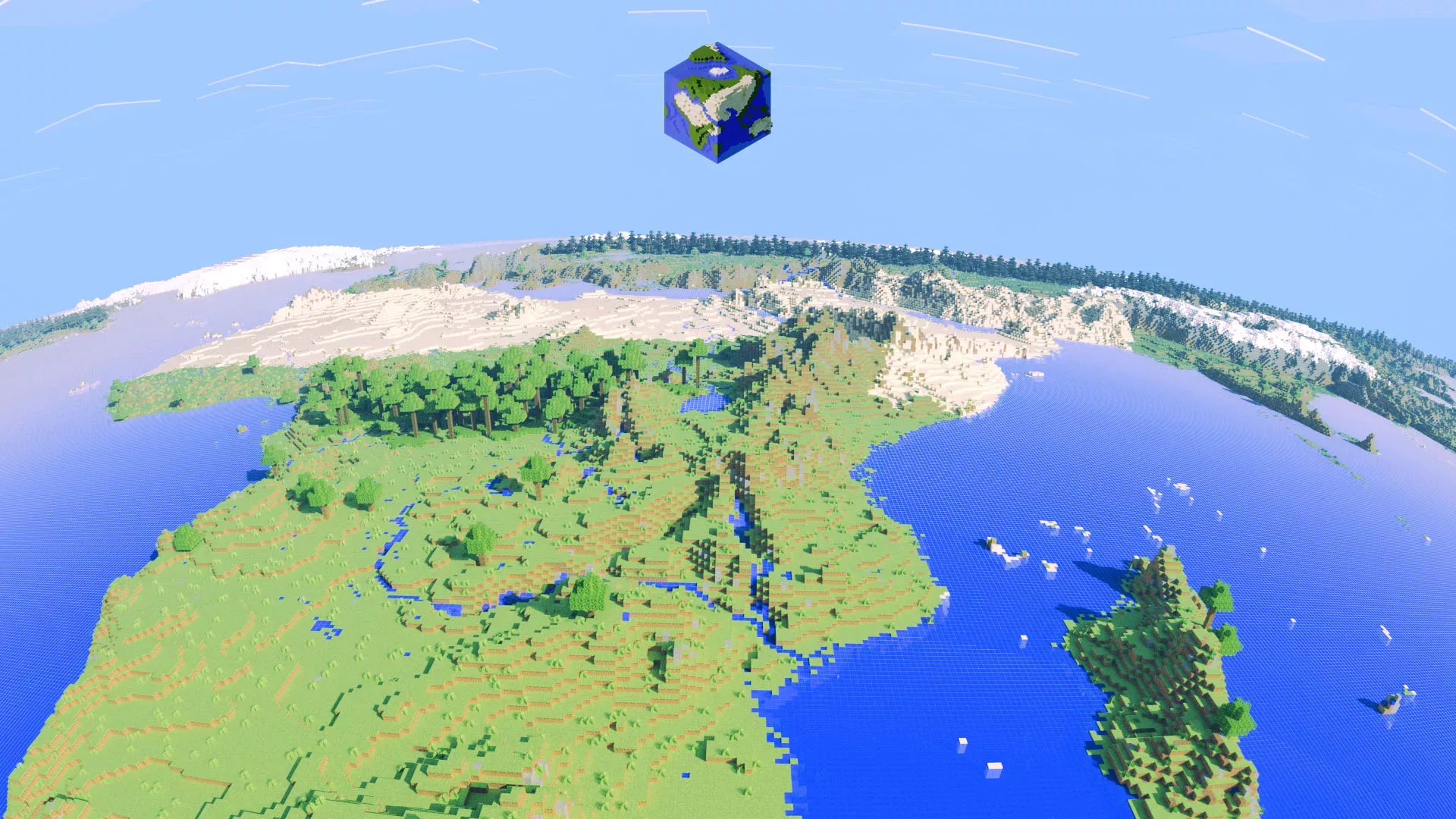

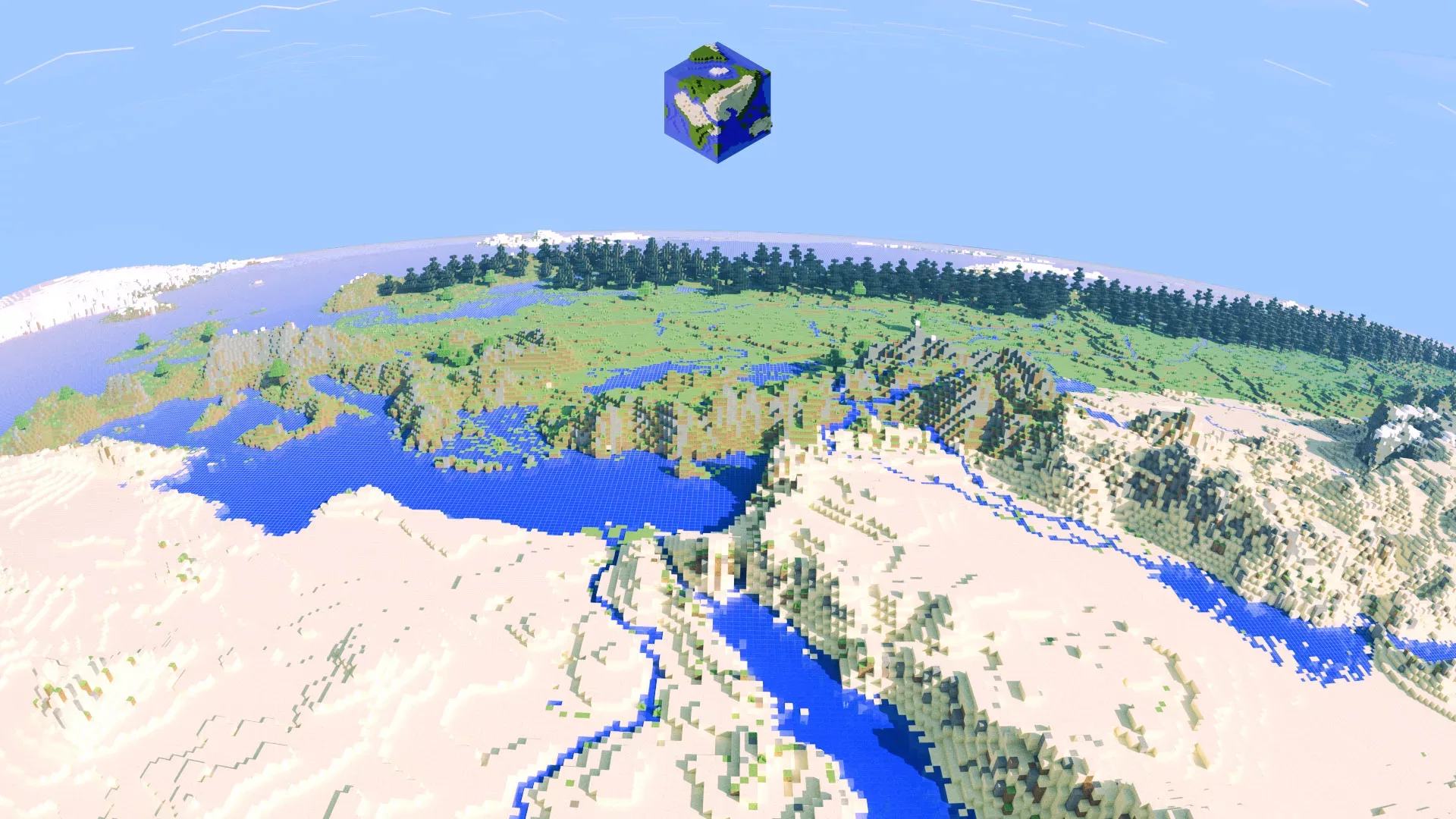

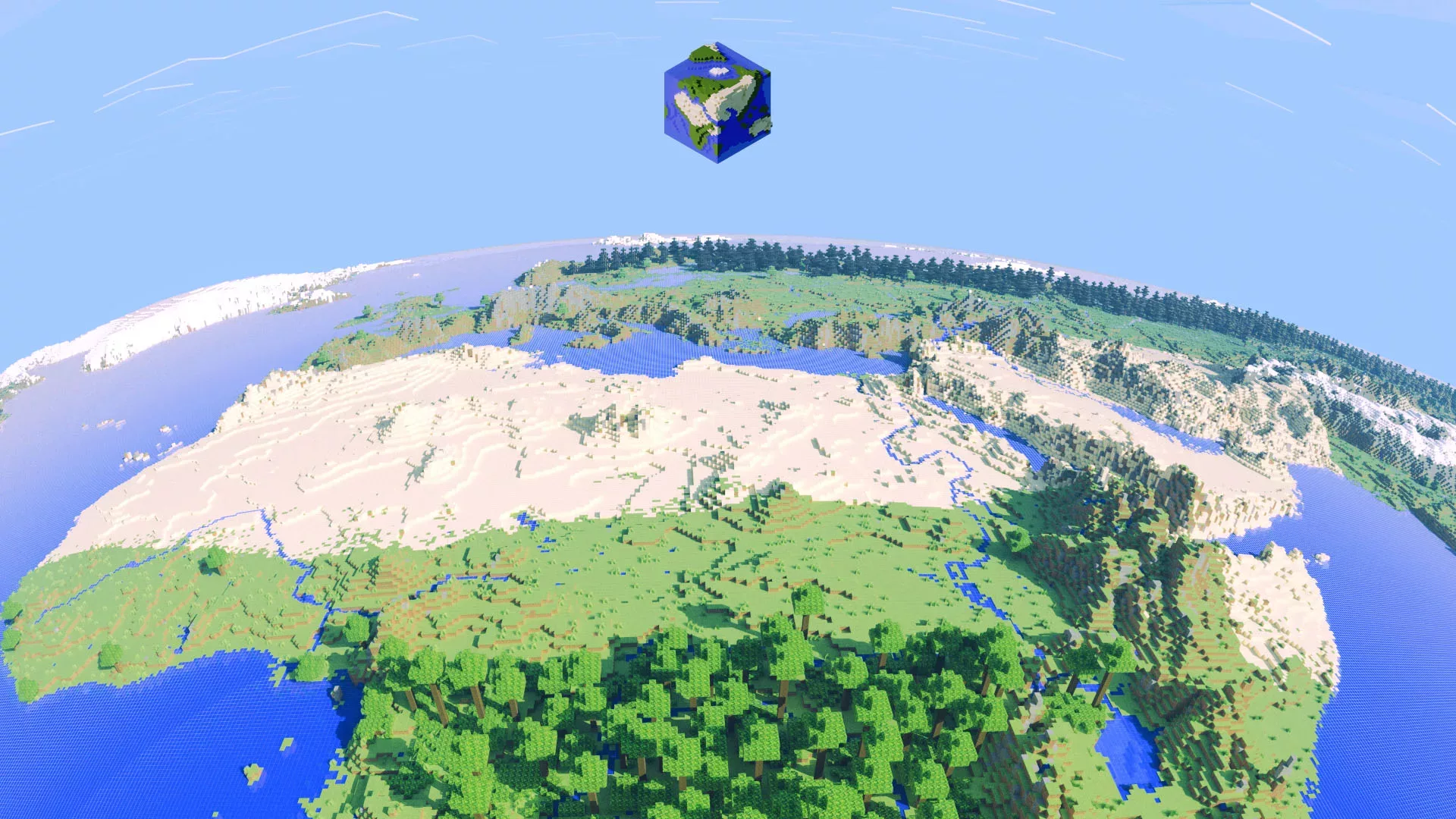

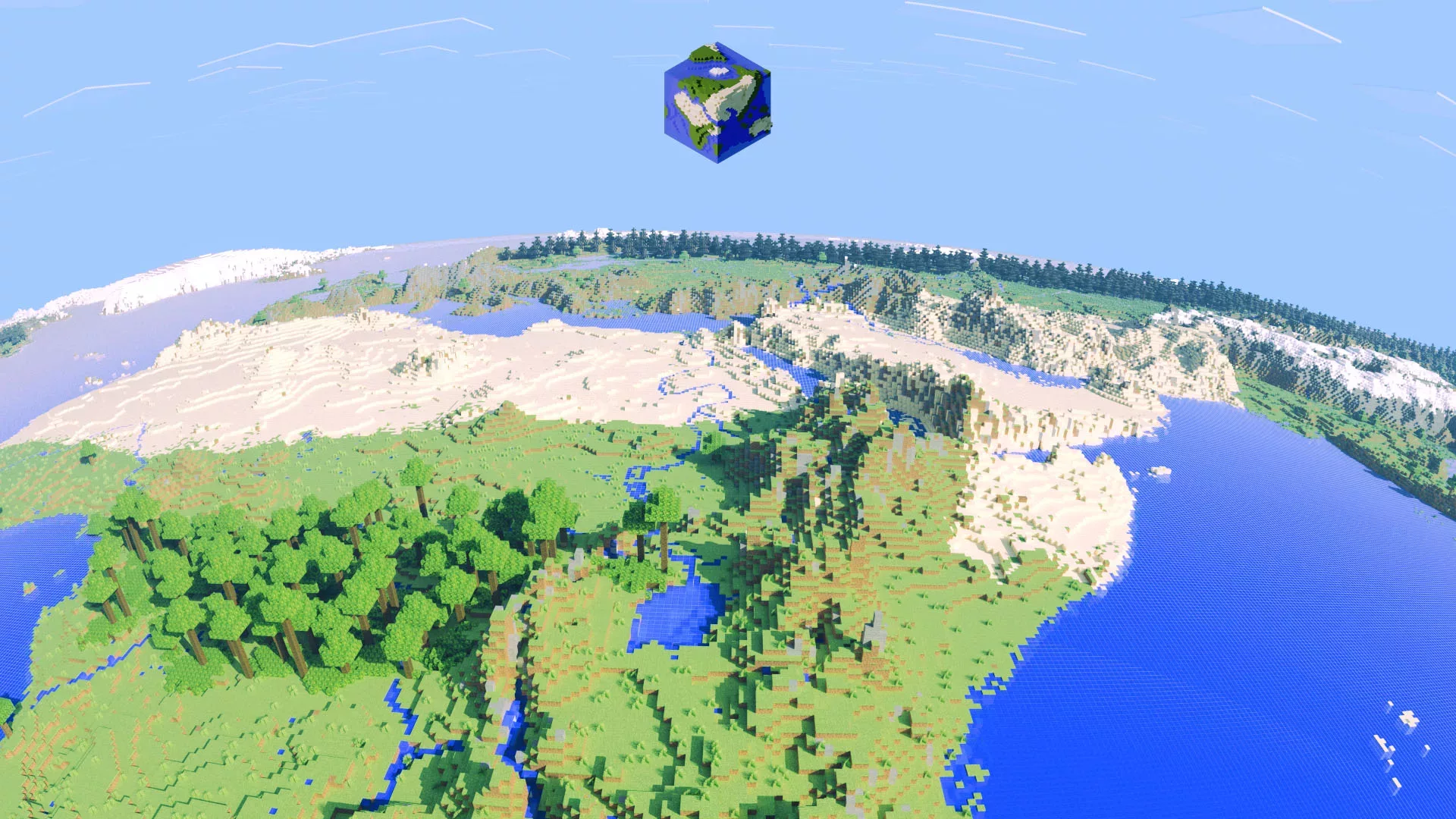

Image carousel

Minecraft is simple. Players mine resources to build structures with one-meter blocks. Users have built everything from a life-size replica of the Starship Enterprise to an 8-bit computer that can run its own games.

Minecraft‘s controls were already familiar to kids around the world. By late 2011, the user base had ballooned to 16 million, cementing the game’s place as a global cultural phenomenon.

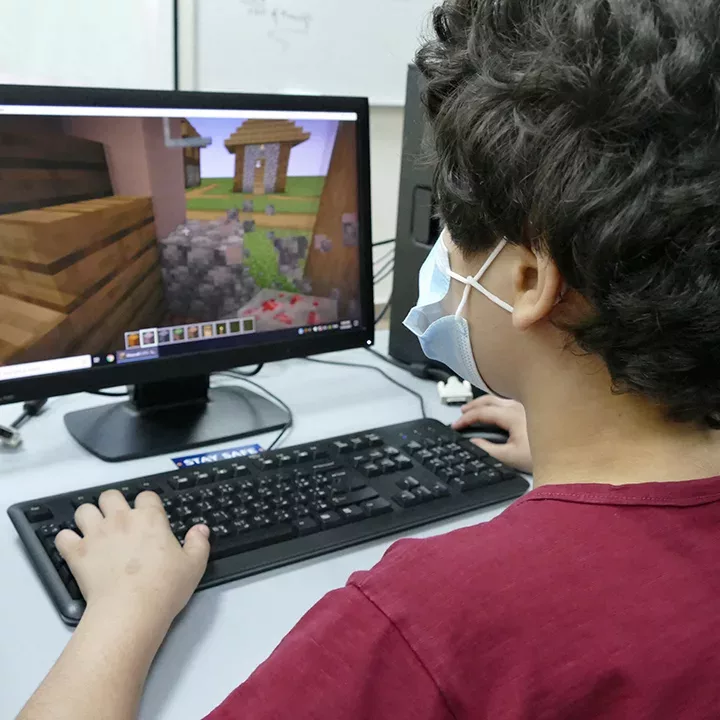

A Swedish consultancy group asked Mojang to deploy a customized version of the game in a series of community workshops across Stockholm County, and invited young people to sketch up proposals for features they wanted to see. Minecraft‘s minimalist interface allowed the group to collect submissions in days rather than months. They called the new project Mina Kvarter, which is Swedish for “my neighborhood” but also translates to “my block.”

Giving the city a voice

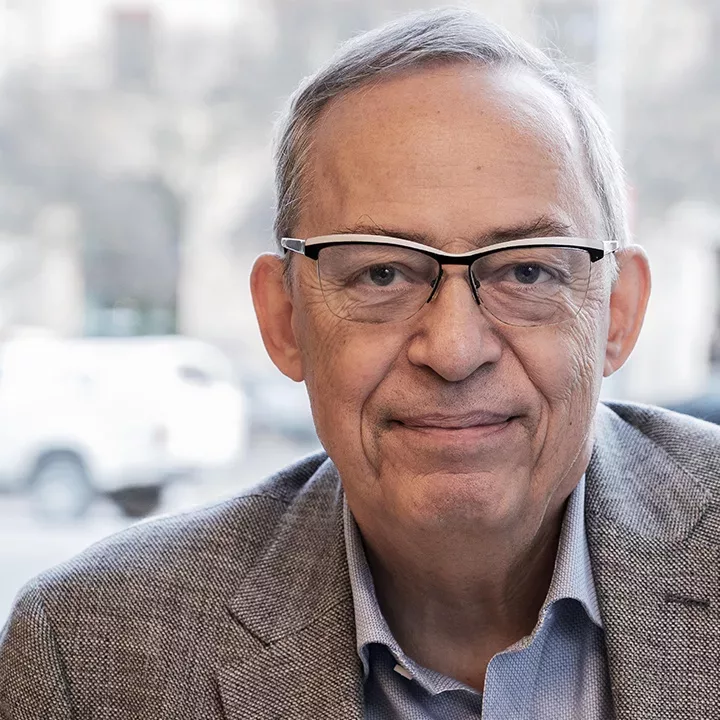

Former architect and urban planner Thomas Melin advises government agencies as a representative of the United Nations. His challenge: How to give residents of the Global South—especially young people—the ability to articulate their needs.

“Traditionally, cities are designed by middle-aged men who drive cars. Who really needs public space the most? It’s not a middle-aged man with a car who is driving out to his golf club every weekend.” –Thomas Melin

“Young people in the Global South are the majority of the population,” Melin continues, “but they are hardly ever included in anything. I saw what Mina Kvarter was doing with Minecraft and I thought, ‘They have a dialogue with the youth of the world. They can help us to talk to the people that we really want to talk to.’”

In 2012, UN-Habitat signed a deal with Mojang at the World Urban Forum in Italy, the United Nations‘ premiere conference on urban issues, creating a new organization called Block by Block.

“Block by Block is a non-profit that gives young people and communities the opportunity to design public spaces within Minecraft. The organization then provides these designs to local governments and architects who in turn draw up plans and eventually bring them to life with funding provided by Block by Block and UN-Habitat.”

To date, more than 30,000 people—mostly women, children, refugees, elderly people, and disabled people—have participated in Block by Block workshops. The organization estimates their projects have impacted more than 2.3 million lives.

Since Minecraft is so simple and intuitive, Block by Block can dramatically reduce the time to plan and implement projects. This speed is particularly useful in disaster recovery efforts.

We were very, very quick, in the flooding in Mozambique. And after the [2015] earthquake in Nepal, [Block by Block] released money in something like 24 or 36 hours, when usually it takes weeks.

In conflict-torn Kosovo, communities need inviting public spaces where people can feel safe to gather and play. A former green market in the city of Pristina had been abandoned. Block by Block invited children to help the city reimagine how the site could be transformed into an appealing, multifunctional public space. What was once an overgrown concrete slab sandwiched between a busy road and a retaining wall is now an outdoor gymnasium, playground, skate park, picnic area and more.

In Beirut, the foundation quickly sprang into action. Block by Block‘s hope is that by adding more greenery, seating and railings—safety and livability features suggested by area youth—they can coax life back to three historically-significant public staircases.

We‘re not just doing this to have a physical improvement, It will have a psychological impact too.

The simple act of giving people the tools to communicate what they want out of their living spaces diverges from the traditional top-down approach to urban development. These projects point to a future where residents can have a louder voice in decisions that will deeply affect their quality of life. With any luck, the staircases in Beirut will reverberate once again with the sounds of city life, and serve as a blueprint for making public spaces more livable around the world.

Block by Block around the World

Block by Block has catalyzed the revitalization of urban neighborhoods in 48 countries, impacting the lives of more than 2.3 million people. Explore a few of them with our interactive map.