plugged in

The new Xbox Adaptive Controller will make gaming accessible to people with a broad range of disabilities.

Dan Bertholomey awoke in a hospital in June of 2010, four days after a hit-and-run driver almost killed him while he was riding his motorcycle, to the sinking knowledge that he'd lost the use of his right arm and hand.

As he lay in his hospital bed, Bertholomey pondered his future. He thought about his daily life and the things he loved to do. How am I going to game again, he wondered? He'd been an avid gamer since age 10, when an original Pong console from Sears magically transformed his family's television set into an electronic playground that he could control. Bertholomey was instantly hooked. He loved the competitiveness of gaming, loved the places it took his imagination.

Bertholomey continued gaming into adulthood, playing often with his son and daughter. In 2005, when he was 40, Bertholomey placed sixth on “Madden Nation,” a televised competition of the U.S.'s best “Madden NFL 06” football video game players. For him, gaming wasn't just a hobby, something he did in his spare time. It was a lifestyle.

You can't fathom losing something that you love so much,

said Bertholomey, 52, who lives in Mesa, Arizona. It's incredibly devastating.

Bertholomey began looking for ways to play with one hand. He found someone to hack him a foot pedal that connected to his Xbox, but it didn't work well for him. He eventually taught himself to play with his left hand, but it was awkward and he couldn't play at anywhere near his previous capacity.

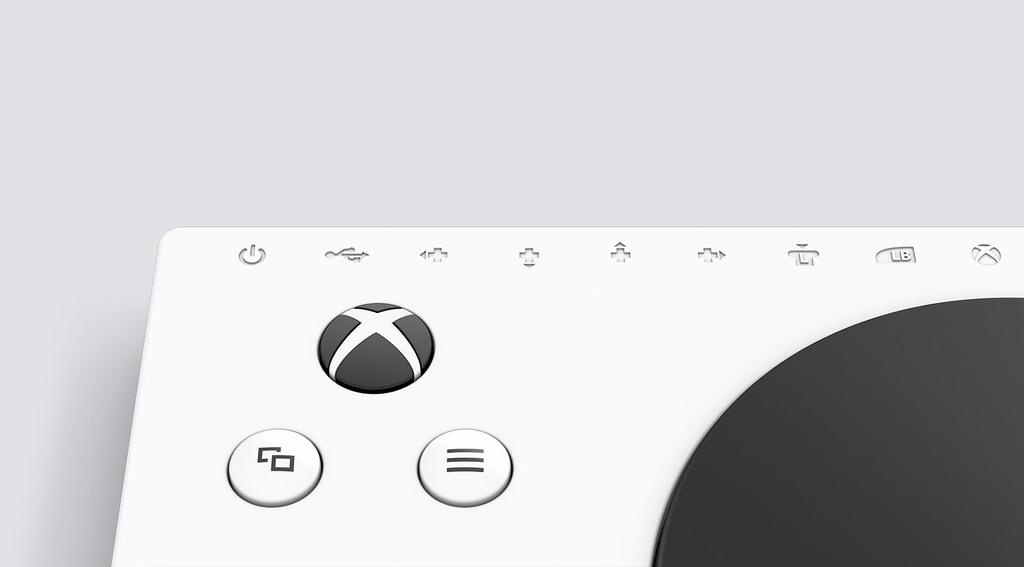

The solution Bertholomey needed is now a reality — and it has the potential to make gaming accessible to players with disabilities worldwide. The new Xbox Adaptive Controller can be connected to external buttons, switches, joysticks and mounts, giving gamers with a wide range of physical disabilities the ability to customize their setups. The most flexible adaptive controller made by a major gaming company, the device can be used to play Xbox One and Windows 10 PC games and supports Xbox Wireless Controller features such as button remapping.

Bertholomey, who is among a select group of gamers who tested the device, said the controller makes it easy to create different setups for various types of games and seamlessly switch between them. Gamers can set up three different gaming profiles on the controller and don't need to reset the device every time they change games, as they sometimes do with modified controllers.

The possibilities are endless,

he said. There's so much you can do with it. I've been searching for a one-handed controller for years. I'm so grateful to have a product like this. Microsoft is my hero now more than ever.

With the new controller, Bertholomey is reviving a dream he'd long shelved, but never quite let go of.

I want to compete again in eSports,

he said. The future is bright. The future is exciting.

Solomon Romney, a Microsoft Stores retail learning specialist in Salt Lake City, Utah, has been gaming with the new controller for a few months. Romney, who was born without fingers on his left hand, moved some controls that were difficult to navigate to the Xbox Adaptive Controller through a mix of software remapping and adding switches that he changes depending on the game. Using the device in combination with his Xbox Elite Wireless Controller allows him to play in ways he previously couldn't.

I can customize how I interface with the Xbox Adaptive Controller to whatever I want,

he said. “If I want to play a game entirely with my feet, I can. I can make the controls fit my body, my desires, and I can change them anytime I want. You plug in whatever you want and go. It takes virtually no time to set it up and use it. It could not be simpler.

I get to redesign my controller every day and get to choose how I want to play,

Romney said. For me, that's the greatest thing ever.

The device also represents something less tangible to Romney — inclusion. Growing up, he was always the other, the person on the outside, the one who's different.

Even as an adult, he struggles with being around children, whose blunt observations can sting. A sense of belonging was something he craved but never had. Talking about what it means to have a device created for gamers like him, Romney becomes emotional, his eyes welling.

It goes to the core of everything I am, everything I've grown up with, everything I've experienced,

he said. “It's nice when a person considers you. It's unbelievable when a company does it, when a company thinks about you, designs something for you.

All of a sudden, I'm not the person on the outside.

The genesis of the Xbox Adaptive Controller goes back to 2014, when a Microsoft engineer was scrolling through Twitter and noticed a photo of a custom gaming controller made by Warfighter Engaged, a nonprofit organization that provides gaming devices to wounded vets.

The employee reached out to the organization's founder, Ken Jones, and learned how difficult it was for injured veterans — triple amputees, quadriplegics, vets with traumatic brain injuries — to access the world of gaming, and how time-consuming it was for Jones, a mechanical engineer who started the organization in 2012, to modify equipment for them.

There was a hackathon coming up at Microsoft's 2015 Ability Summit, so a group of employees decided to put together a team with the goal of developing a solution for Warfighter Engaged. Working in consultation with Jones, the team developed a gaming device that used Kinect motion-sensing technology to track a gamer's movements and translate them as if they were inputs from a traditional Xbox Wireless Controller.

The project won the hackathon's top prize and led a different employee team to create another device for Microsoft's company-wide hackathon later that year, a unit that attached to an Xbox controller and allowed users who had difficulty navigating a traditional controller to plug in additional buttons and switches.

“I get to redesign my controller every day and get to choose how I want to play. For me, that's the greatest thing ever.”

The lab is the evolution of everything coming together,

Hunter said. It's an embassy for gamers with disabilities, where we bring them in, we listen to their feedback, we see how they play. They're interested in helping us build better products.

The space has a wall with photos and personal stories about gamers with disabilities, and a living room-style area with a sofa and large screen set up for gaming. Every detail is carefully thought out, from the desks that can be raised to accommodate wheelchairs to the braille signage and dimmable lighting.

One wall features a row of computers and Xboxes with demos aimed at providing a sense of what gaming is like for players with disabilities. There's a desk with two switches attached to the bottom that let a player steer a car in a driving game and propel it forward with a foot pedal. Another station has a Quadstick, a mouth-operated joystick that works by blowing air into or sipping air from it. Simulation goggles emulate what it's like to look at a screen for someone with tunnel vision or partial blindness, and an eyes free

station has a covered screen and an Xbox that reads aloud to players so they can navigate the system without a visual interface.

Education is a very important aspect of this lab,

said Evelyn Thomas, a program manager driving accessibility strategy and development for Xbox. It's a space where employees can come and understand what it's like for gamers who are marginalized by ability and how they play games.

Jenny Lay-Flurrie, Microsoft's chief accessibility officer, said the lab and the new Xbox controller are integral parts of the company's efforts to make gaming more accessible.

Gaming should be fun for everyone, whether you're a person with or without a disability,

she said. “The Inclusive Tech Lab explores how technology can empower gamers with disabilities. Folks are getting together to think through how to make a game not just accessible, but totally awesome for someone with a disability.

There is nothing but potential to make gaming more inclusive for everyone,

Lay-Flurrie said. We absolutely take on that challenge and encourage more gamers to get involved, especially if you have a disability.

In 2017, Microsoft released a new feature for Xbox One called Copilot that links two controllers as if they were one, enabling people to play together without transferring the controller back and forth. That's helpful if a player has trouble operating all of the buttons on a single controller — so two players can team up on a game, for example, with one driving and the other firing. Copilot also allows players to create custom gaming setups that work for them. If a gamer is playing with one hand, a second controller can be linked with Copilot and operated with a head or foot.

The feature quickly became one of Xbox's most popular and is being used in ways its creators hadn't imagined, Johnson said. He mentioned a man who is blind and loved playing video games with his wife before he lost his sight, and rekindled that shared experience through Copilot.

With Copilot, he now has the opportunity to play with her again,

Johnson said. It's opened up such a wide variety of capabilities.

The feature was instrumental in driving the evolution of the Xbox Adaptive Controller. As Copilot moved toward release, Microsoft realized that instead of creating an adaptive device that attached to an Xbox, like the hackathon-generated invention, it could instead develop a stand-alone unit that could connect with another controller via Copilot and accommodate more ports than would easily fit on the initial prototype device. Disabled gamers would get greater flexibility, and the controller would be a more elegant solution than an unwieldy add-on with wires hanging off in various directions.

But taking a product, particularly one designed for a specific market, from concept to completion isn't a straightforward proposition. As plans for the controller moved forward, Microsoft was also launching Xbox One X, the world's most powerful console, leaving deadline-focused Xbox employees with little bandwidth for other work.

And like any other area of the company, Xbox was expected to operate within financial constraints. An adaptive controller wouldn't necessarily generate a significant return on investment. But it was important to Microsoft's goal of making gaming more accessible to people with disabilities, and it spoke directly to the company's mission, implemented under CEO Satya Nadella, to enable every person and organization on the planet to achieve more.

Trying to develop a business case for an accessible product can be very, very challenging, because the scale of the products don't generally make a positive business case for the investment that has to go in,

said Leo Del Castillo, who was the general manager for Xbox hardware when the controller was being developed.

You have to look at your return on investment in a way that is not just financial.

Castillo and a core group of dedicated employees helped push the project forward. Securing the needed approvals wasn't always easy, and it meant convincing the right people that an accessible device was worth the outsized investment. Hunter was among the project's dogged champions.

I had a passion for it and I didn't give up,

she said. I kept saying, 'This product is too important. It's too important to Microsoft, it's too important to Satya's vision. If we really want to be intentional and we really want to walk the walk versus just talk the talk, this is the product that will do it.'

Microsoft has intensified its focus on inclusive design, an approach that involves identifying potential barriers and designing products for people with a wide range of abilities. The philosophy is a priority across the company, from Xbox to Office, and has led to accessibility features being built in to various products and apps. But the Xbox Adaptive Controller is the first piece of hardware launched by Microsoft that was developed through an inclusive design approach that included extensive consultation with gamers who have disabilities.

Creating the controller involved dozens of employees across Microsoft, from engineers to product testers. Since the device is the first of its type from the company, determining what it needed to best serve gamers with disabilities was challenging, project manager Gabi Michel said.

We know how to make a controller, and we know how to make a really great controller,

she said. But we didn't know how to make a really great accessible controller.

So the project team turned to the experts, consulting with gamers, accessibility advocates and nonprofits that work with disabled gamers. Their feedback helped shape many of the controller's features, down to its packaging. The 19 jacks across the back of the device, mimicking the number of inputs on a standard controller, are spread out in a single line rather than being stacked so they're easily accessible for people with dexterity challenges. The controller's rectangular shape is designed to sit comfortably in users' laps without falling between their legs or requiring them to sit in an awkward position.

After discovering that some gamers arrange their gaming setups on a lap board, often securing them with Velcro, the design team added three threaded inserts to the controller so it can be mounted with industry-standard hardware and attached to a wheelchair, lap board or desk.

Giving them the ability to put the controller where they need to have it was a really important aspect of the design,

said Chris Kujawski, the Microsoft senior industrial designer who worked on the project.

Symbols embossed along the rear edge at the top of the controller identify each port on the back so users don't have to lift or turn the device around to find the right one. And grooves above each port provide a physical reference to help guide plugs into them, a feature that Microsoft is now considering adding to other products.

An early prototype of the device had the D-pad and other controls between the two large A and B buttons on its top. But after listening to feedback from gamers, the team moved the controls off to the side and slid the two buttons closer together so gamers can rest a hand between them and easily move between the buttons.

Other changes included rounding the controller's edges to reduce the impact if it's dropped on a foot, and lowering and softening the front edge so users can slide their hands onto the device without having to lift them and also rest them without discomfort. The sloped design provided an unexpected benefit.

Although that wasn't the intent, we found that angling that surface made it easier to use the controller with your feet, because it presented the buttons to your feet in a more natural way,

Kujawski said.

The controller is the first piece of Microsoft hardware developed through an inclusive design approach.

In the early days of video games, input was simpler. Controllers just had a single digital joystick, or a rotating wheel, and maybe a button or two. But as the industry evolved in the 1980s and ‘90s, controllers, systems and games themselves became increasingly sophisticated and challenging to navigate. The simplicity of the dot-eating Pac-Man gave way to characters who had to jump, shoot, run, battle enemies and navigate their way through dizzyingly fast, multilayered scenarios.

Those complexities have meant that gamers with disabilities are often limited in what they can play — or even shut out of gaming altogether. With 65 percent of American households playing video games in 2017, according to the Entertainment Software Association, that's a significant cultural segment to miss out on.

Part of why gaming is important to people with disabilities is because gaming is important, full stop, across the board,

said Ian Hamilton, a game accessibility specialist and consultant who lives in England. It is a really deeply entrenched part of our culture now, which makes it a really big deal to be excluded from.

April Dickerson understands that as well as anyone. As a child growing up in rural Tennessee, Dickerson would try to play basketball or football with the neighborhood kids, but it was hard to keep up. She was born with spinal muscular atrophy, a progressive disorder that impacts muscle movement. Video games offered an escape to a world with few limitations.

In real life, if you have any kind of different abilities, you're constantly trying to adjust to what you're doing,

said Dickerson, now 39 and an avid gamer. But in video games, everybody can have the same experience.

Dickerson switched to PC-based games about eight years ago, after she was no longer able to navigate a traditional controller. How to accommodate players like her is a question the gaming industry, including Microsoft, has been grappling with for years. Given the highly personalized nature of disabilities, a one-size-fits-all solution has been elusive. One gamer might be able to play a particular game, while another with the same disability can't. A gamer who is blind has different challenges than, say, a gamer who plays without hands.

Gaming has long been a culture of hackers, players who are constantly looking for tricks or workarounds to gain an advantage over opponents or play games in different ways. Disabled gamers emerged over the decades as a subset of hackers, modifying equipment themselves out of necessity, while nonprofit organizations sprung up to help meet their growing demand for assistive gaming technology.

Steve Spohn was among those early DIYers. He began gaming at around age 5, when his mom bought him an Atari. But as his spinal muscular atrophy progressed, Spohn had trouble operating a controller. He switched to PC-based gaming, but that became problematic too. At one point, struggling to use a keyboard, Spohn used a dental hygienist tool as an extender, resting his hand by the space bar and using the tool to reach the upper keys.

I had been doing stuff like that for years,

he said. “My mom taught me that you take an everyday object and repurpose it for something you need it for, and that's how you continue surviving in the world. So I would get a faster mouse or a keyboard with the buttons spread out differently. But eventually, the off-the-shelf solutions stopped working.

When I was at the point where I was just no longer able to use the keyboard, I started panicking, because gaming was a large part of my life,

said Spohn, who now plays with a Quadstick. That's when I needed to turn to a place for help.

That place was The AbleGamers Charity, a West Virginia-based nonprofit launched in 2004, where Spohn is now the chief operating officer. Like Warfighter Engaged, the organization provides disabled gamers with custom setups like modified controllers and devices that allow them to play with their eyes. Spohn is among the experts Microsoft consulted with in developing the Xbox Adaptive Controller, and he believes the device has the potential to help many gamers.

It's going to be a great controller for those who need it,

he said. This has been such a long time coming.

Plug

and

Play

Drag or use arrows

to rotate 360°

Drag or use arrows

to rotate 360°

Drag or use arrows

to rotate 360°

Drag or use arrows

to rotate 360°

Bill Donegan works for the U.K.-based nonprofit SpecialEffect, which also provides assistive technology to disabled gamers. He said the Xbox Adaptive Controller will ease the organization's workload and provide the flexibility its clients need.

We're often cobbling together all sorts of things to get a similar effect. We use accessibility switches for almost everyone we work with, so in terms of the flexibility, this is going to be amazing for us,

he said. It makes our job far simpler, because we can concentrate on positioning switches and joysticks for the user rather than trying to cobble things together.

“Part of why gaming is important to people with disabilities is because gaming is important, full stop, across the board.”

It was a big surprise, and it still is,

he said. We can't quite believe it's happening.

Hamilton said the controller is a significant advancement in the gaming industry's efforts to increase accessibility.

The progress across the industry is being felt through all kinds of initiatives, but going to the extent of manufacturing commercial hardware is really a different kind of level,

he said. “The kind of commitments and process involved in that make it a really powerful statement of intent. You don't commit to an endeavor like this unless it is something that you really passionately care about.

There have been great people within Microsoft pushing for game accessibility for a long time,

Hamilton said. But for those efforts to translate into lasting cultural change, you also need top-down support, people at higher levels who understand and care and want to empower their staff to be able to push on forwards — people like Phil Spencer and Satya Nadella.

Spencer, executive vice president of gaming at Microsoft, said the new controller advances the company's commitment to enable all gamers to play.

Gaming can be one of the great equalizers and great unifiers for society, but we need to do more to broaden that audience,

he said. “The Xbox Adaptive Controller represents the positive impact technology can have, when that technology is designed to include as many people as possible.

Whether someone lost the ability to play or they've never been able to try gaming in the first place, this controller will hopefully make having fun in the gaming community a possibility.

That morning, as Snead evaded enemies and completed her mission, her pain momentarily melted away.

I went to my happy place for the first time since the accident. It made me feel comfortable, like life was back to how it was before everything happened,

she said, smiling. I felt at home for the first time, like I was really at home.

The hospital, which specializes in rehabilitation for patients with spinal cord and brain injuries, tested the new Xbox controller as part of its Adaptive Gaming Program. The program started three years ago, after a new patient who was a passionate gamer arrived at the hospital. The young man was depressed and unwilling to take part in his therapy sessions. If he couldn't game, he told his primary therapist, he didn't see the point in doing anything.

The therapist reached out to Erin Muston-Firsch, an assistive technology specialist at the hospital, and asked if she could help. Working with the hospital's rehabilitation engineer, Muston-Firsch put together a crude customized gaming setup for the young man. It looked like Frankenstein,

she said, but it worked.

Other patients noticed and wanted in on the action, and their interest led Muston-Firsch to set up the gaming program. She built up a stock of assistive gaming devices and taught her coworkers how to use them. But the setups were kludgy and complicated to set up. Sometimes they crashed, as the patients sat waiting. Their disappointment pained Muston-Firsch.

It's terrible if you set somebody up on something you think is going to work and get their hopes up, and then watch them struggle and get discouraged,

she said. And in the past, if one controller didn't work, it may have taken you 10 or 15 minutes to get that all set up for them, and now you have to take it all apart and start over.

We can build and switch as they're playing and not have to ask them to be patient, when they're in a whole world of having to be patient,

Scroggs said. They'll say, ‘I used to be a gamer,' and we'll say, ‘No, no, you are a gamer and we're going to figure this out.' I think that's one of the biggest things it's done for us.

And the controller's $99.99 price puts it within reach of gamers who might not be able to afford other typically pricey adaptive technologies, Muston-Firsch said.

Price point was a big deal when Microsoft was talking to us about this controller. Having something affordable is huge,

she said.

On a Thursday evening last spring, half a dozen patients at Craig Hospital gathered in the hospital’s therapy gym for its weekly gaming night. As his mom, Wendy, looked on, 22-year-old Hamilton Coke played “Madden NFL 16.” A gamer since getting his first Xbox at age 6, Coke played regularly until February, when he injured his spine in a ski accident.

When I got hurt, I was literally laying in the snow thinking about all the things that I wouldn't be able to do,

he said. At one point in ICU I was thinking, I probably won't be able to ski or surf again, but I really hope I can get my fingers back so I can still play video games.

Coke has been playing with the Xbox Adaptive Controller and appreciates how easy it is to hit the buttons. It's very helpful,

he said. It's pretty cool.

Nearby, Snead was taking down enemies in Call of Duty,

with Muston-Firsch providing scoping assistance using Copilot, while her family members cheered her on.

We just got done saving the president!

she announced, chuckling.

One of Snead's brothers, Exzavier Harris, who frequently plays with her at home, was impressed by the new Xbox controller. He liked its lightness and shape. He liked how it sat easily on a lap. Most of all, he liked what he saw it doing for the gamers.

With that controller, they're having fun,

he said, watching the patients play. I see how it's making my sister happy, and I like that.

Originally published on May 16, 2018. Updated on September 4, 2018. Original photography by Andrew Kist, Brian Smale, Daniel Victor & Swanson Studio.