Sarcos’ snake robot could be coming to a small space near you – to save lives

Aboard a timber-hauling ship in calm waters, one crew member climbed down into a cargo hold. He collapsed. His crew mate, sensing trouble, dashed down the same ladder for a rescue. He collapsed. Then their chief officer descended to investigate. He collapsed.

All three men died. Their cargo ship, the Suntis, was offloading at a British port on that spring day in 2014. The timber had absorbed air below deck, causing a lethally low oxygen level in the hold and asphyxiating the crew, investigators found.

That tragedy – underscoring the hundreds of worker deaths that occur in confined spaces annually around the world – offers a use case for a new, cloud-connected snake robot built to crawl into perilous places that put people at risk.

The Guardian S, a compact, camera-equipped device that slithers atop its magnetized tracks, can maneuver down a vessel’s hold, roam near haz-mat spills or creep into the line of fire at a police standoff – nearly anywhere its human operators need it to go, say engineers at Sarcos Robotics, a global leader in the development and production of robotic systems.

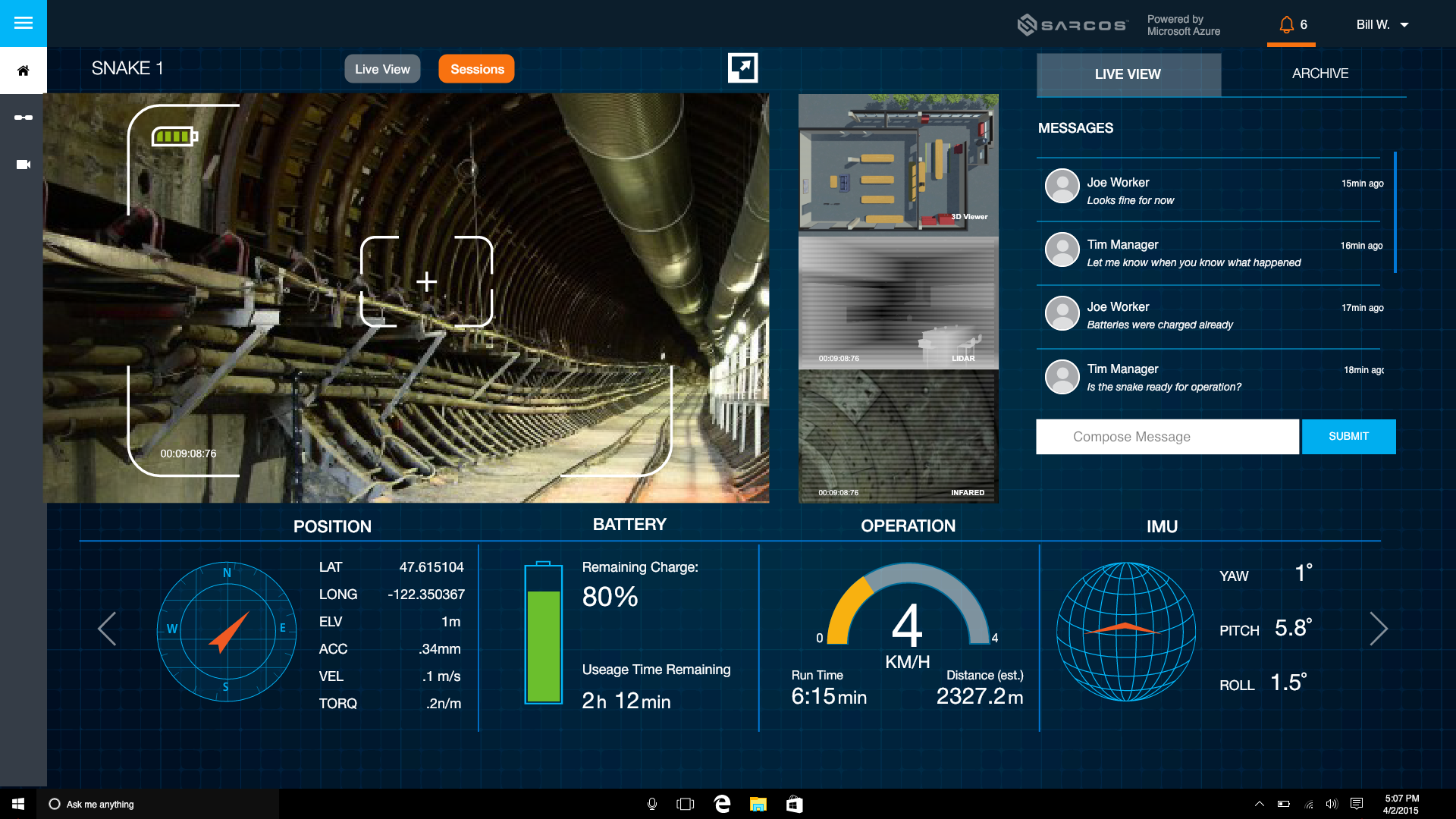

Packed with sensors, the snake bot feeds still images, video and real-time environmental data to Microsoft Azure, offering its operators – or offsite analysts – up-close intel on heat, leaks, structural damage or toxic fumes, says Ben Wolff, co-founder and chairman of Sarcos. The company is based in Salt Lake City.

“We’re going to keep people out of harm’s way,” Wolff says. “In each of those cases, we are not eliminating humans because humans still have to operate the robot. But we are creating that degree of separation from the dangerous location.”

In 2015, 136 U.S. workers were killed during incidents in confined spaces, according to a recent report by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The government lists tunnels, pipelines and ship holds as prime examples. That death rate exceeded those of the previous decade when the average was 96.

In January, three Florida construction workers died after inhaling toxic gases while inspecting a pipeline below a street. Their deaths were eerily similar to what happened aboard the Suntis – the first man never came out, prompting the second and third men to conduct fatal searches.

“If we had sent our snake robot into that manhole with a suite of gas sensors, that could have sent back real-time information – as well as catalog information for the future about what it was discovering down there,” Wolff says. “We could have potentially saved those three lives.”

Across the maritime industry, where cramped spaces are designed to boost efficiency and save weight, nooks and crannies are common at job sites like shipyards and oil platforms over water. But those tight spots are ideal quarters for the Sarcos snake bot to deploy then scope out cracks in vessel holds, corrosion in pipelines or weak seams in refinery tanks, Wolff says.

To assess and detect deterioration or anomalies, the Guardian S can be hand-carried to the precise place an operator needs to inspect. Weighing 13.5 pounds, the robot and its components are packed in a small plastic case, suitable for a trunk or backpack and about the size of a traveler’s carry-on.

Once removed from the case, an operator can turn it on, allowing the Guardian S to wirelessly synch with a Windows-based tablet that’s fitted with joysticks for steering the device and touch-sensitive screens that show the snake’s movements.

“We’ve tried to keep consistent with the perception that the younger generation is inseparable from game controllers,” says Dr. Fraser Smith, Sarcos president.

The waterproof robot is lowered, hand placed or driven down a wall or through an opening to reach a structure, traverse uneven terrain or head underwater, and the mission begins. The smart machine’s suite of onboard tools extends the operator’s human senses for a deeper look into a dangerous space.

Four cameras, which swivel in all directions, feed a steady picture and offer a chance to record video or snap high-res stills, marking the coordinates of any concerning spots. LED lights illuminate dark corners.

“On your screen, you see what the snake sees,” Smith says. The tablet also shows motor temperature and battery life. The snake bots can observe for 18 hours minimum.

Two-way audio allows operators to listen to an environment (or offer calming words, in the case of police situations). Sensors, configured to a customer’s specific needs, can report the temperature and humidity. Probes can be placed directly on a structure’s surface to hunt for cracks or weaknesses, and sonar can ping sound off the surface to similarly check for soft spots in welds or seams.

Its design enables the snake to move forward, backward or side-to-side, and to roll back over if it flips during its journey. A degree-of-freedom design that’s built into its center helps the robot twist into many configurations, including a “Z” shape, to increase its stability and squeeze through tricky topography.

But what makes the robot truly unique is the cloud-connected sensors on board that link the device with the Internet of Things (IoT), Wolff says. As the snake collects and streams live environmental data, company operators working far away can document, analyze and better understand the cramped spaces they’re safely inspecting.

“This has the potential to enhance precision because it’s not just what one person may see when they are in a tank or the hold of a ship. The images can now be captured and shared with multiple people around the world and analyzed later by others,” Wolff says.

In April, Sarcos made the Guardian S commercially available, offering it primarily through robot-as-a-service agreements. To date, six pre-production models are with customers, Wolff says.

He recently spent time at the Microsoft AI & IoT Insider Lab in Redmond, Washington to evolve the Guardian S from an Android-based robot to a device that’s embedded with Windows 10 and integrated with the Azure IoT Suite.

“When you can collect meaningful sensor data and then allow people around the world to make use of that sensor data, it fundamentally changes the robot,” Wolff says.

Eventually, Wolff says the snake bot will be capable of machine learning, meaning it will examine large amounts of data to sniff out patterns and predict structural problems.

“The machine will be able to identify anomalies with its cameras and then be able to learn – through interaction with the cloud and with humans – what types of anomalies and what types of corrosion are more important to pay attention to,” he says. “That’s part of our future roadmap.”

Top image: Guardian S on display at the Digital Difference conference in New York, April 26, 2017. (Photo by Brian Smale)