By Michael Hainsworth

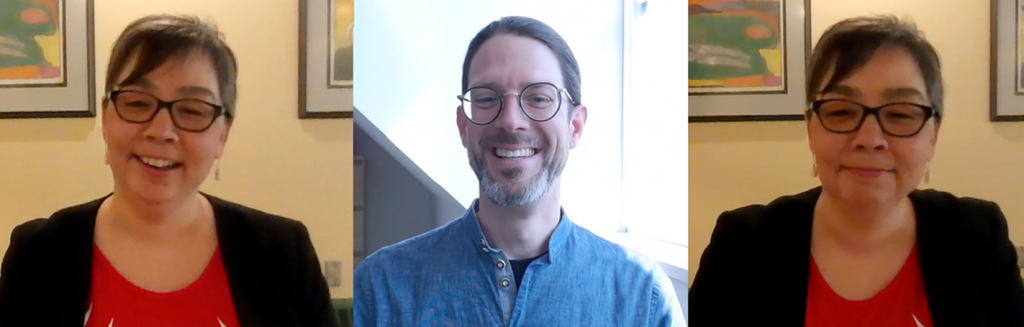

The days of science fiction’s “universal translator” are closer than we think, thanks to a huge shift from rules-based programming to the art and science of artificial intelligence. “I’d say by the end of the decade,” says Microsoft Principal Data Scientist Christian Federmann, “and if that doesn’t happen, you can come back and grill me about it.” Getting back to Federmann comes via an unusual route: The far-North. It’s in Nunavut where Microsoft Translator is getting it’s latest workout with the addition of Inuktitut, in an effort to preserve Indigenous culture. Inuktitut is the primary dialect of Inuktut, the language spoken by the country’s Inuit indigenous peoples.

2 out of 3 Inuit speak Inuktitut today, down 10% from 15 years ago, and falling. “Our language is beautiful. I would encourage everyone and anyone to learn it,” says Nunavut’s Inuit Language commissioner Karliin Aariak. Aariak is tasked with ensuring both government and the private sector comply with the territory’s law while encouraging its peoples to learn the language. “I’ve always said if a language does not change or evolve, it’s a dead language. So our language needs to evolve.” It has. Aariak points out Inuktut didn’t have a word for “Internet”, and the community’s elders arrived at “Ikiaqqijjut”, the term used to describe the other worldly journey a Shaman spirit takes during their practice. There still isn’t a term yet for “artificial intelligence”, but Aariak says it’s coming.

What does the territory’s language commissioner think about the potential of Microsoft Translator for Inuktitut? “The longer we’re using this, the more rich it will be, the more usable it will be.” That’s the secret to machine learning algorithms: the more they’re trained, the better they get. Artificial Intelligence, and machine translation in particular, is based on vast amounts of parallel data. If data scientists have only a handful of sentences or a handful of hours of conversation, then it is highly unlikely that they can build great translational models right out of the gate. It’s equally unlikely that they can build great speech recognition models. “It’s an art,” cautions Federmann.

The technology behind Microsoft Translator has practical applications beyond converting advertising and road signs. For example, a conference phone can identify who is speaking and transcribe the meeting without the need to take notes. Federmann enthusiastically forecasts, “you just ask the system, okay, give me the meeting notes and a super nice by-product here is that once you have a transcript, which is coming in on a rolling basis, it’s really easy to send that to the translation service and get it translated into whatever language.” Microsoft Translator is available for any developer to incorporate into their technology today.

And if there was just one word Aariak had to describe the future of her language?

“Unity.”

And what would that be in Microsoft Translator for Inuktitut?

ᐊᑕᐅᓯᐅᖃᑎᒌᖕᓂᖅ.