Bridging the STEM divide: AI hackathon helps young women excel in computer science

Computer science? That’s boy stuff. Or so 15-year-old Hesme believed when she switched schools in 10th grade. “I thought I’d be terrible at it,” she says. Her former school in Durban, on the coast of South Africa, didn’t offer comprehensive science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) classes.

But when she moved to Curro Heritage House High School in Morningside, Durban, STEM classes were going to be a regular part of the curriculum. She was nervous about that —but when her brother dared her to take a computer science elective, she accepted the challenge to prove him wrong.

To her amazement, she loved it. “It became my passion,” she says now, in her final year of high school. As the only girl in the class, at first she felt intimidated but ended up thriving. And when the call came out to try out for an all-girls artificial intelligence (AI) hackathon, she immediately began writing the required motivational letter to apply.

“I was just sitting in class, writing, and all my passion came out,” she says. When chosen to be on a five-girl team representing South Africa, she was ecstatic.

Today, Hesme is developing her own AI-based app to help people like herself — diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum — to better cope when interacting with the world. She plans to get a higher-level certificate in AI next year before going on to study computer science at university.

And she was thrilled when her team won second place in the first all-girls edition of Microsoft’s Imagine Cup Junior virtual AI hackathon held in cooperation with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), in celebration of International Women’s Day.

“AI captured my heart over that weekend,” says Hesme, whose team competed against 16 others from 11 countries across Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

Business as usual doesn’t give equal opportunities to girls

The gender gap in education is serious. More than 130 million girls were already being denied education before COVID-19 hit. And as schools around the world closed, UNESCO estimated that 11 million additional girls are at risk of never going back to school.

This could mean a big step back after years of slow-but-steady progress towards gender equality. It also puts young girls at risk of adolescent pregnancy, early and forced marriages and gender-based violence. Even before COVID-19, the rate of change wasn’t fast enough, according to Justine Sass, chief of the Section of Education for Inclusion and Gender Equality at UNESCO. UNESCO partnered with Microsoft on the hackathon under UNESCO’s Global Education Coalition’s Gender Flagship which unites more than 70 institutions from the United Nations, civil society, academia and the private sector to help minimize the effects of COVID-19 on education and gender equality.

UNESCO believes curtailing girls’ education ultimately impacts the entire world. In an era when jobs increasingly require digital skills, educating girls can boost local and regional economies and fight poverty. But it’s not happening fast enough.

“Last year was the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration,“ says Sass, referring to the U.N. declaration of ensuring equality for women around the world. “If we continue at this rate, we won’t get every girl into primary school until 2050.”

And still, two-thirds of the illiterate adults in the world are women, she says.

“It’s been the same proportion since 2000, so we’re not making progress in that area,” says Sass.

If the point of education is to open up equal opportunities for children and young people, regardless of their gender, it’s not working.

You can’t be what you don’t see

A critical first step is to expose girls to positive female role models in STEM fields. Girls who know a woman in a STEM profession are significantly more likely to feel confident when doing STEM coursework (61%) than those who don’t know a woman in a STEM profession (44%).

Unfortunately, most girls simply don’t have those kinds of role models in their lives. When asked to describe a typical scientist, engineer, mathematician or programmer, 30% of girls sketch out male personas. Even adult women do the same (40%) — including 43% of the women who work in STEM themselves.

“At UNESCO, we’re often looking to address gender stereotypes — for example, in textbooks — and offer more equal visions of a world,” says Sass. “We need to start small. Who’s represented as a politician and who’s represented in the kitchen in the books students see in school?”

Perhaps even more importantly, recent Microsoft research shows that girls don’t see how a STEM career can be creative and have a positive impact on the world. But staging “interventions” in the form of giving girls role models and exposure to real-world STEM applications, educators have the power to dramatically change their minds.

One study found that participating in a proactive “role-model intervention” increased girls’ STEM interest by between 20% and 30%. This is precisely why UNESCO seeks to engage female role models, including teachers, to close digital and STEM gaps in the classroom through initiatives such as YouthMobile, which was mobilized to support this first All-Girls Edition of the Microsoft’s Imagine Cup Junior Virtual AI Hackathon.

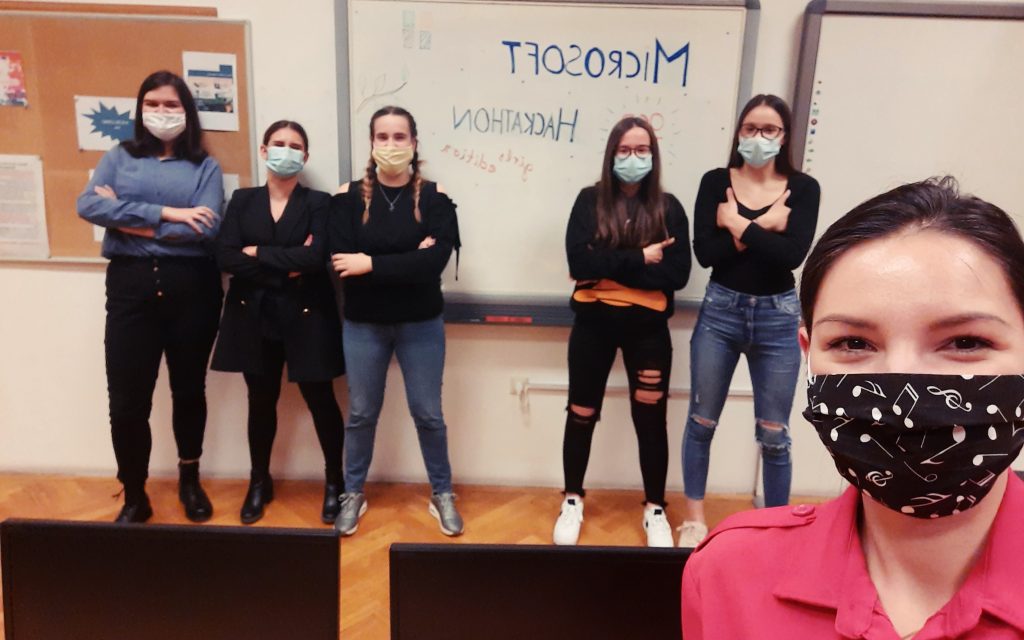

“We don’t have older girls showing that they are capable,” says Karla, a senior from the High School of Math and Natural Sciences, in Osijek, Croatia, a small town on the Drava River. Her team placed third in the hackathon. Perhaps they exist, she says, but “they’re not speaking up about it, and showing the rest of us what they are doing.”

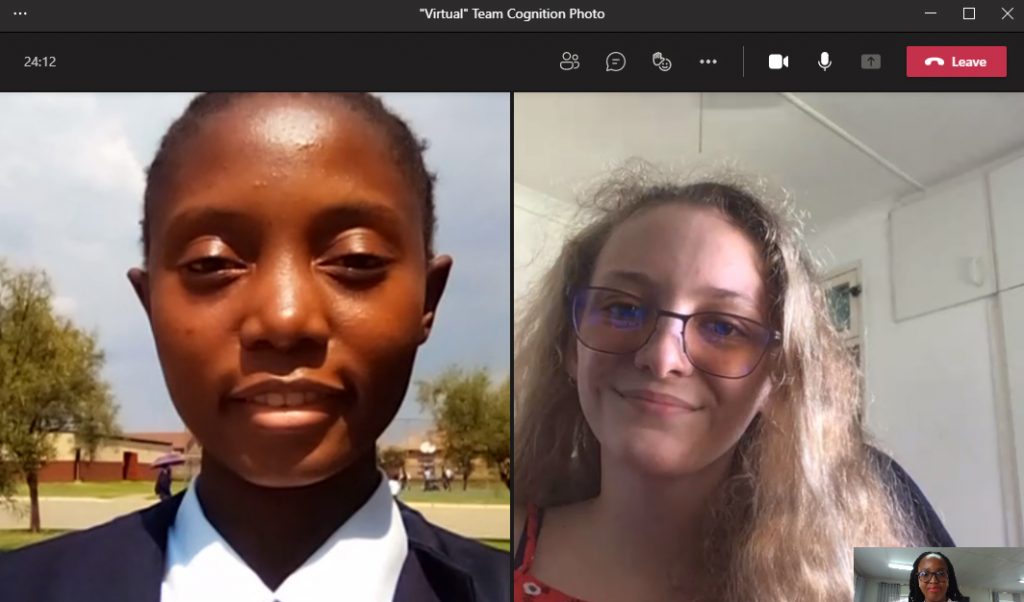

Precisely because of this lack of visibility of women in STEM, it was empowering to participate in the hackathon alongside more than 80 girls from countries throughout Europe, Africa and the Middle East and receive advice from other women in the field, says Anamika, a third-year student at the Corro Waterfall High School in southern South Africa, and a member of the South African team.

It was honestly inspiring to see all these women, so high up in male-dominated fields, who have achieved so much and gone so far.

Hackathon as an intervention to interest girls in AI

The theme of the hackathon focused on AI for Earth and sustainability. The only prerequisites were that the girls be between 14 and 18 years old and have an interest in STEM.

Prior to the hackathon, the participants were assigned homework and “leveling up” activities that introduced them to coding. During the two-day virtual event on Microsoft Teams, they were invited to attend talks from women in STEM fields and participate in hands-on workshops where they worked together on practical exercises designed to teach them how AI could be used to solve real-world problems using AI prediction modelling and techniques, such as decision trees and random decision forests.

The ultimate challenge presented to the teams: use the AI tools they’d learned to come up with a way to save a species.

Team Clustering from Spain won first prize with their AI solution meant to preserve the Mediterranean Sea. The team first predicted the future evolution of sea temperatures using linear regression in Python, a programming language. Then, they used image classification to identify the most polluted areas. Bringing these two sets of data together, the team created a machine learning model to reduce pollution, while preserving the area’s marine species.

Team Cognition from South Africa placed second with an AI solution for saving African wild dogs. The species is endangered because of habitat loss, disease, predators, and human behavior. Leveraging image classification and anomaly detection, the team first located the areas populated by wild dogs, and gathered data regarding any human activities or otherwise dangerous conditions for the dogs in those areas. Then, through satellite images and image recognition, the team tracked the wild dogs’ behaviors. Using anomaly detection, they could decide when to intervene to save the at-risk wild dogs population.

Team OCR from Croatia won third place with their plan to save griffon vultures, which play an important role in the natural cleaning cycle in their country. Using neural networks, a series of algorithms that recognizes underlying relationships in data, the team first identified which areas are habitable for the birds. Then they identified the griffon vultures using image classification. Finally, the team used regression to predict possible increases or decreases in griffon vulture population, to help authorities make intervention decisions.

Most of the girls went into the hackathon feeling nervous and unsure of themselves, according to Nokuthula Mnguni, an information technology teacher who was a mentor for the South African team.

“They really didn’t know whether or not they had the correct skills that were needed,” she says. “But given the opportunity, they ended up finding strengths they didn’t even know they had.”

In a way, the problem they were assigned distracted them from their fear of the technology, says Inmaculada Morena Lara, a computer science teacher who was the mentor for the Spanish team, from the Santo Tomás de Aquino-La Milagrosa High School in the small Spanish town of Tomelloso.

“They were focused on solving a real-world problem,” she says. “They weren’t thinking about AI concepts or subjects. They didn’t realize all the things that they were learning. They were not studying a subject; they were solving a problem.”

Leapfrogging technology for its own sake to achieve bigger dreams

In 2018, Microsoft commissioned research to investigate girls’ attitudes toward STEM, expecting negative results. “But surprisingly, we found that actually they were quite positive about STEM and technology,” says Alexa Joyce, Microsoft’s Future-Ready Skills Director, who answered questions and shared advice during the hackathon for young women looking to change the world through AI.

“Typically, you hear, ‘Oh, girls think technology is hard or boring.’ But our research didn’t bear that out,” she says. Instead, girls were clearly interested in using technology to be creative and address issues that would impact the world. It was the application of the technology — not the technology itself — that fascinated them.

Third-year Spanish student Andrea Rodríguez Limón agrees. There’s currently a big push in Spain to try and interest girls in STEM. But Rodriguez has always dismissed the posters and public service messages posted in school hallways and on buses that attempt to convince her to go into a tech career.

Because they are focused on building and programming machines, and full of technical jargon, “They don’t appeal to girls. They don’t know how to talk to girls. If they want to interest us they have to try another way,” says Rodriguez.

“Tell them that it’s something they can use to save the world, and they are with you 100%,” says Joyce.

This generation is very aspirational. They want to be engaged with something bigger than themselves.

Sass says we cannot afford to live in a world where scientific and technological solutions are desperately needed and yet exclude half of the world’s talent needed to help create them. “There’s still a huge amount of bias in AI. A lot of that is because men are still driving the agenda and we don’t have enough women contributing.”

COVID-19 also remains a huge concern, with huge numbers of countries moving towards remote learning or hybrid learning, raising serious concerns that girls aren’t learning in those contexts because of the existing gender digital divide, says Sass.

“Our initial data coming in is that all of those inequalities are likely to be exacerbated because of COVID-19,” she says. “There is actually a huge opportunity right now for us to close some of those gaps and to really use technology to its advantage. It’s an opportunity to open more pathways for girls to develop digital skills and drive more equal futures for themselves.”