Access granted: Helping people with disabilities explore the places they love

Life is more interesting for Jean Marc Feghali after 9pm.

The rest of the day is relatively uneventful; it’s the final few hours as the sun sets that are a challenge, especially if he isn’t at his London home.

The 23-year old has Leber’s Congenital Amaurosi, a hereditary condition that causes pigmentation of his retina – the cells in the thin layers of tissue at the back of his eyes have been dying since he was born.

Every day, the “tunnel” of vision he sees through deteriorates further in step with the sun’s fading light, turning even the simplest journey at night into trek fraught with potential obstacles.

The UK’s long summer days are a tool for Feghali to do what he wants to do – stay at home or go out with friends, for example.

Accessibility in the UK can be a big problem. Many towns and cities are hundreds of years old, so updating public buildings can be difficult, and repairing pavements and roads is not a straightforward decision for cash-strapped councils.

Microsoft for Startups is helping many young companies develop technology that can help people with disabilities safely navigate the areas they live in. There are 11 businesses in the current AI for Good cohort and all of them are graduating on June 4.

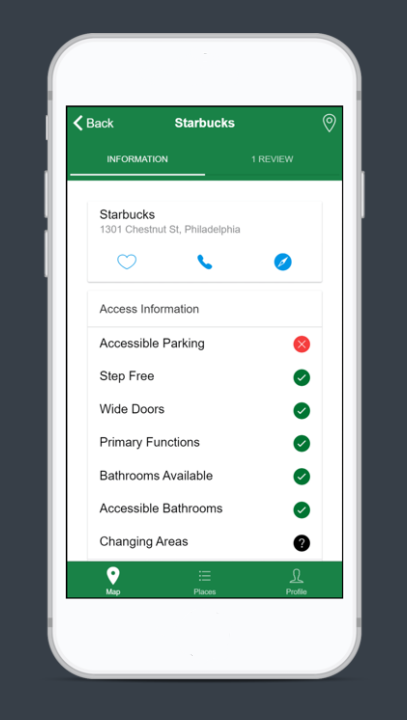

Access Earth, which lets people find and rate places based on their accessibility needs, is one of those benefitting from the US company’s advice, support and products.

Another is WeWalk, which has created a product that fits onto any cane and uses ultrasound sensors to warn visually impaired people of high obstacles such as tree branches. The device can also be paired with a mobile phone for navigation and other digital features. Feghali, a PHD researcher at Imperial College London, is advising the company.

“I see very little at night, and I often miss things in front of me,” he says during a meeting at a Microsoft office. “It’s like wearing very dark, tinted sunglasses. I have an idea of where sources of light are but never obstacles that can hit me, like trees for instance. The issue with things like trees and signs is their bases are so small that you can wave your cane and it’ll probably miss those obstacles. However, with the ultrasound sensor, the WeWalk device will vibrate when something is a certain distance away. You can manually set that distance, too.

“My WeWalk will ring when a set of trees is over there, but when it vibrates, I know something is going to be just over here. I swipe the cane once, OK I know there’s no tree over here, so I can walk forward now. It’s given me confidence. I can now swipe the cane left and right, know that something is there, which I wouldn’t have found before, and move past it.”

As WeWalk can be screwed on to the top of any cane, Feghali now exclusively uses it when he goes outside. Before leaving his house, he links WeWalk to his phone via Bluetooth, enabling a host of other features that can be used solely by interacting with WeWalk’s buttons, touchpad or by turning the cane or striking the end on the ground – audio navigation cues that guide him to destinations, bus timetables that are read aloud (in Turkey it uses Bluetooth technology to tell you when your bus is approaching and instruct the driver to stop), or asking his phone to make a sound if he’s misplaced it, are some examples.

WeWalk also contains an accelerometer, gyroscope and compass, allowing more possibilities when it comes to creating apps and programs for WeWalk. That will also create vast amounts of data that will help Gokhan Mericliler, an entrepreneur specialising in social innovation who is leading the WeWalk project on behalf of Turkey’s YGA, understand how partially-sighted people are using the device, so it can be developed further.

That information, like the WeWalk platform itself, is hosted on Microsoft’s secure cloud, Azure. Meanwhile, the four-month Microsoft for Startups programme offers the company a curriculum designed by the ScaleUp team, Social Tech Trust team and the Microsoft UK AI team. They get access to workshops that will help develop their product and take them to the market. They will also hear from inspiring speakers and take part in Q&As.

Mericliler, 34, believes using Azure alongside Microsoft’s artificial intelligence technology can take the device to the next level, helping more visually impaired people leave their phones in their pockets, rather than carry them in their hands in order to hear navigation and message alerts. That’s not very safe or practical, if you’re holding a cane at the same time.

“Voice capability is the one of the crucial things that we want to develop using Microsoft technology because it enables us to develop WeWalk in a more custom way,” he says. “We want our product to be a daily companion for visually impaired people and for them to be able to use it in every aspect of their lives. It will be a unique device for them.

“We can enhance it using Microsoft technology. Voice commands, for example, will be one of the core functionalities of WeWalk because visually impaired people use voice technology much more than others. We currently support English and Turkish, but Microsoft’s platform supports more than 60 languages, so we can easily make WeWalk available in 60 different languages, too.”

WeWalk emerged out of a hackathon two years ago and has recently completed an initial production run, with roughly 1,500 units now being used across the world. Plans to increase that number are already under way, amid talks with visual impairment organisations and charities in Germany and Scandinavia, as well as the Swiss National Association of and for the Blind (SNAB) and the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) – the largest cane distributor in the UK. The pair are also looking at integrating Transport For London’s open real-time information system to help people move around the capital, and there is also a partnership with Wayfindr, a UK non-profit organisation that’s empowering people with visual impairments through audio-based navigation.

Feghali and Mericliler are keen to point out that this is only the first iteration of WeWalk. They would like to use Microsoft’s world-class AI and machine learning algorithms to develop new features, understand how their product is being held and used, and how people move in social situations.

Mericliler suggests that WeWalk could one day “talk” to traffic lights to help users cross roads without needing to locate and push a button, or help firefighters identify where people with sight loss are located in a building.

Those are concepts at this stage but even so, the demand from the public is still likely to be huge. According to the RNIB, 250 people in the UK start to lose their sight every day, and as of 2015 more than two million individuals are living with sight loss that is severe enough to have a significant impact on their daily lives, such as not being able to drive. Almost half of those say they would like to leave their home more often.

One-in-five people aged 75 and over is living with sight loss, rising to one-in-two for those aged 90 and over. As humans live longer, the number of people living with sight loss is estimated to rise to 2.7 million by 2030. By 2050, it will be more than four million.

There is a significant economic cost, too. Only 27 per cent of blind and partially sighted people of working age are in employment. The RNIB estimates the cost to the UK economy of sight loss in the adult population of the UK totalled £28.1 billion in 2013. This figure comprises both direct and indirect costs, as well as costs associated with reduced health and wellbeing due to sight loss.

“Disability technology should fit into your day as easily as getting on a bus,” Feghali adds. “When you get on a bus, you don’t think, ‘Oh, I’m on a bus right now, I love this bus’, you just sit down and wait because it’s a necessity to get to where you need to go. That’s how disability technology should be; it shouldn’t be something that calls attention to itself, but something that integrates into the way you behave.

“That’s why the potential [of WeWalk] is huge. It’s really revolutionising what a cane can do but only evolving the things you have to do to be able to use it, which I don’t think happens enough in the technology industry. WeWalk has certainly evolved the way I walk and the way I interact with a cane. It’s positioning itself to be an all-in-one, perfect companion for those with a visual impairment.”

That’s a big ambition for a start-up. Feghali admits that creating technology for people with partial sight loss is much harder than for those who are completely blind. The black and white scenario of sight and darkness now becomes a cornucopia of shades of grey, because only the individual knows how much they can see and therefore do on their own. Suddenly, a product that works for one person doesn’t work for another.

That applies to navigating towns and cities more generally, too. Last week, Microsoft announced it was partnering with Moovit to provide its multi-modal transit data to developers who use Azure Maps, and a set of mobility-as-a-service solutions to cities, governments and organisations. The partnership will enable the creation of more inclusive, smart cities and more accessible transit apps.

These tie-ups are important for creating a world where accessibility for all is the norm. Currently, visiting a coffee shop in a small village in Cumbria might be easy for someone who is completely blind, but a couple of steps could make it impossible for someone using a wheelchair. Going somewhere new can create a number of challenges.

Disability technology shouldn’t be something that calls attention to itself, but something that integrates into the way you behave

That’s where Access Earth is trying to help. The free app lets users find places that suit their own accessibility needs, based on the reviews of people who have already been there. So, if you were visiting a city or town for the weekend, you could use your phone to easily find out if the hotels, restaurants and venues you wanted to visit had step-free access, wide doors for wheelchairs, and accessible parking and bathrooms, among other things.

Those who are “mapping” locations via the app simply click “yes” or “no” for each feature.

It was created by Matt McCann, Chief Executive, while he was studying Computer Science at Maynooth University, just outside Dublin. A terrible trip to London convinced him there was a gap in the market for a publicly supported app for people with disabilities.

“I had booked a hotel in London around the time of the Paralympic Games in 2012,” the 29-year-old says. “The hotel told me they were wheelchair accessible but when I arrived there were three steps up to the entrance and I couldn’t fit my Rollator inside the hotel room. If it wasn’t accessible to me, it’s definitely not accessible to someone in a wheelchair. I thought there had to be a way to easily communicate that information, to put the power of information back into the hands of the user. That’s what sparked Access Earth.”

McCann teamed up with Donal McClean, now Chief Operating Officer, and the pair developed the idea by entering Microsoft’s Imagine Cup – a global competition that sees computer science students create applications that shape how we live, work and play.

With staff numbers growing to five, the ambitions for Access Earth are now also global. The app is available in almost every country, and is proving very popular in cities such as Philadelphia, in the US, and Sofia, in Bulgaria, where the team work with local care centres and other non-governmental organisations (NGOs). There are now more than 2,000 places rated across Philly, for example.

“We find that local engagement is very effective,” says Ciara Moran, Chief Product Officer. “We say ‘OK, you are a community of people who are actually going to use this in your area, you are going to map your town, looking at hundreds of places and rating them’. Once that’s done, we usually see engagement grow, because you’ve already met your users.”

McCann adds: “There are a couple of veterans organisations we work with in the US and we found that once we work with some of their chapters, they’re more than happy to help because it gets their members out and about, and into areas of cities they haven’t gone to before. The biggest feedback we’ve had is that Access Earth has helped people to experience places they didn’t think were accessible.”

Like WeWalk, Access Earth is also hosted on Azure, helping the company’s expansion and spikes in demand. It, too, is embedding Microsoft’s AI and machine learning services into its technology, which will allow the app to automatically recognise accessibility barriers, such as steps, when a photo is uploaded. Being able to control the app using your voice is another feature McCann and Moran are looking at.

The free Azure credits that are handed to every company in the Microsoft for Startups programme have been a huge help in developing those new ideas, as has the hands-on help that the team receives.

“There’s a lot of support there,” Moran, 25, says. “The workshops and the mentoring that we’re getting in different areas of business is fantastic. I’ve been able to say things like ‘social media is not my thing’, and they will set aside time for me.

“Microsoft also has a great network of people. The speakers that have come in haven’t said: ‘we’re here to do a two-hour talk and then it’s goodbye’, they want you to add them on LinkedIn and ask them questions. That follow-up help has been great.

“We’ve had lovely offers from Microsoft to put us in contact with people they know, such as local governments and football clubs. All the resources are just there for us.”

Councils, event organisers and football clubs are the biggest focuses for Access Earth at the moment, and they are finding it’s an open goal – organisations are desperate to make themselves accessibility-friendly, they just don’t know where to start.

McCann adds: “It’s about education. We visited an old manor house in Ireland that’s open to the public, and they told us the only reason they don’t let people go up to the second floor is that they don’t know what to do if there is a fire. The reality is you can get products that go on wheelchairs and stairs to allow for safe evacuation.

“Once they know about those kinds of things, we find that organisations are more than willing to make those accommodations, but right now they’re taking the default stance of ‘we don’t know’.”

According to Scope, there are 13.9 million people with disabilities in the UK, with a combined spending power of £249 billion a year.

Moran agrees, but also points out that 65% of people with disabilities are reluctant to spend money on leisure and travel, partly because of the hassle involved.

“There’s a massive, untapped market there for accessible tourism and opening up your community and your area for an influx of people who’ve seen it as a place for accessibility,” she says.

McCann offers one example of a grocery shop in his local town.

“The store had one or two steps up to the front door, but they didn’t see that as a big issue,” he says. “We pointed out to the owners that I would struggle to get up there and that someone in a wheelchair definitely wouldn’t, and that would make those people go down the street to another shop. The owners took that on board, because we came back three months later to find they had put in a ramp, paid for with a grant from the local council. They said were now serving people using crutches and canes, and also parents with pushchairs. Once we pointed it out, they realised how large a market they were unintentionally excluding, just because they thought it was only one small step.”

Moran adds: “What it really ties into is this mindset of universal design, which is, if you make it accessible for everyone, it benefits everyone.”

The Access Earth team may suggest a few small changes that councils and businesses could make so they would appeal to more visitors, and there are often grants available to help, but the app is not about finding accessibility issues and demanding change. McCann and Moran want to put the power of information in the hands of those who really need it, so they can make their own decision on whether they could visit that location. As Moran puts it: “We are trying to relieve that fear of the unknown.”

Through their work, McCann and Moran are creating “people power” around the issue of accessibility. Individuals of all abilities often tell the pair they are now noticing steps and narrow doors that they would have otherwise simply not thought about.

By encouraging people to map their own areas, the hope is that Access Earth becomes the “go-to” app for hundreds of millions of people who have a disability and their families and friends.

Moran says: “Our primary goal is to map the world with accessibility information so that no matter where you go, whether it’s your local coffee shop or to Japan for a holiday, you’re seeing this information in the same way for each place.”

This week their focus, like the founders of WeWalk, will be on London. Their cohort’s graduation will take place on Tuesday, June 4, at the Microsoft Reactor, and all the businesses will hear from Microsoft UK Chief Operating Officer Clare Barclay.

Feghali, Mericliler, McCann and Moran hope it is the first step (or roll of the wheels) towards creating a truly accessible world.