Empowering Kenya and the world with high-speed, low-cost Internet

Before affordable Internet access came to Nanyuki, a town of 30,000 nestled near Mount Kenya 125 miles north of Nairobi, Red Cross representative Anthony Kuria had to close the office and walk hours to the nearest hot spot to send an email. He’d often return to a line of waiting people who needed his help.

Worse, when the inevitable fire or flood came and families became separated, snail mail and bulletin boards were the best tools Kuria had to help people find their loved ones.

Today, thanks to the dream of two rose farmers, a Scottish-born visionary and a partnership with innovators and the local government, Kuria and the Red Cross, along with Nanyuki’s schools and its young entrepreneurs ― many of whom don’t have electricity ― have reliable, affordable Internet access.

And it’s changing their lives.

“The Internet is the great leveler. Particularly as you connect people who thought they’d never get it,” says Malcom Brew, founder and chief technology officer of Mawingu Networks, which provides the town’s Internet access. “The Internet changes how you can run yourself as a community. If you’re not connected, you’re on the wrong side of the digital divide.”

In fact, for every 10 percent growth in Internet access, the GDP growth in that country is likely to increase by 1.38 percent. “That’s phenomenal,” explains University of South Hampton economist Richard Thanki. “With this kind of growth, poverty, school enrollment, stunted nourishment are all changed for the better. If anything, that impact is likely to increase as time goes on.”

In the shadow of Mount Kenya, where the weather can change at a moment’s notice, Nanyuki is dominated by rugged desert scruff and dotted by trees that appear windswept even when the air is still. It’s also inhabited by colorful, friendly and proud people. Children chase each other and boda boda motorbikes down dusty streets. Donkeys carry the afternoon’s crop home.

The downtown is a series of pastel-colored, low-slung cinderblock buildings, topped with tin roofs and advertising services and goods for sale on brightly colored placards. It’s the kind of place where it’s not uncommon to hear music playing and people singing.

Beyond Nanyuki, Laikipia County stretches through the valley, a patchwork of farms, ranches, homes and a collection of villages.

Mawingu, which means “cloud” in Swahili, transmits its wireless signal using underutilized broadcast bandwidth, known as “TV white spaces,” and solar power. It’s fast, affordable and reliable, says Haiyun Tang, chief executive of Adaptrum, a Silicon Valley-based startup that was one of the early pioneers of TV white space technology, who with Brew, and Microsoft, helped launch the effort in rural Kenya.

Brew calls it “nomadic” Internet.

The Mawingu pilot project in Nanyuki, which began three years ago, now connects eight customer locations, five schools, the Laikipia County government office, Laikipia Public Library, Red Cross and the Burguret Dispensary healthcare clinic.

And it’s having an impact.

Gakawa Principal Beatrice Ndorongo Beatrice reports that in the two-and-a-half years since the connection was established, students at Gakawa Secondary School have improved their scores in every single subject on the Kenya National Exam.

Mawingu is part of Microsoft’s 4Afrika initiative to improve global competitiveness in Africa. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella visited Kenya, and Nanyuki, to celebrate the launch of Windows 10, and to and see firsthand how technology can transform people and organizations.

“When I think about the true opportunity of technology in years to come, it’s true empowerment that spreads more evenly,” Nadella says. “And that is the opportunity here.”

Inspired by the promise of Mawingu’s initial pilot operations, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (the U.S. government’s development arm) last week signed an agreement indicating an interest in loaning the network $4 million.

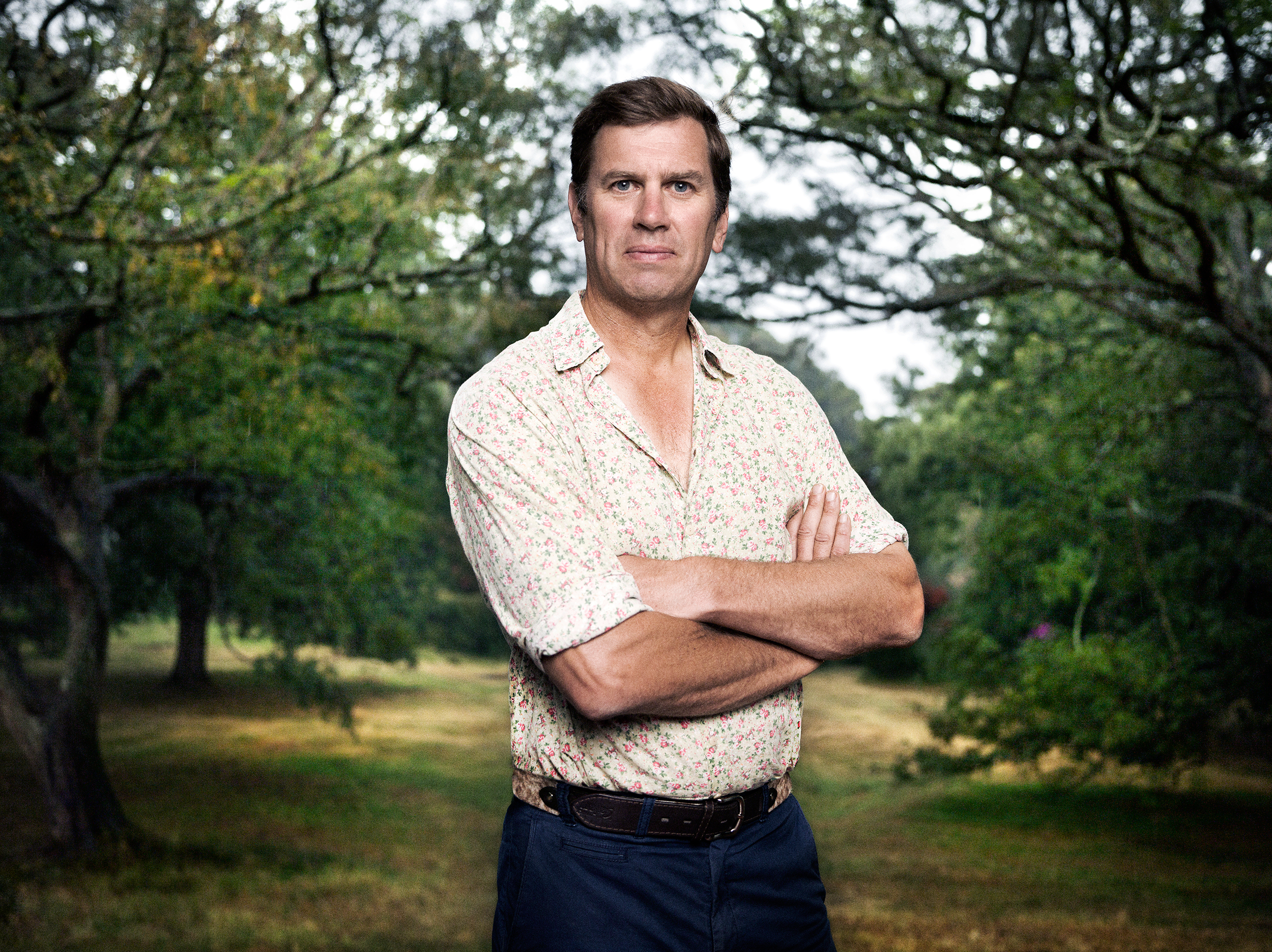

Tim and Maggie Hobbs moved to Kenya from the United Kingdom 20 years ago, purchased a derelict former dairy farm just miles from the equator, and set out to grow the perfect flower.

Set amidst arid plains and lush rolling hills, the combination of just the right year-round temperature, and just enough rain, makes the region near Nanyuki one of the only places in the world ideal for cultivating high-quality, long-stemmed scented roses. The Hobbs’ company, Tambuzi, sells 50 varieties of garden-scented roses to florists around the world; 5 million stems a year. They employ 500 people from nearby Nanyuki.

Three years ago, a chance meeting between the Hobbs’ and Brew, an old friend, planted the seed that’s grown into Mawingu in Nanyuki today. Maggie Hobbs remembers hearing about what Brew had been doing with TV white spaces off the coast of Scotland.

“He was explaining about this project he was working on. I said, ‘If you’re looking to try this in rural Kenya, I’ve been working with the schools in Nanyuki for 15 years. And by the way, I’d quite like it to come here. It would be amazing for our community.’”

Maggie Hobbs affectionately calls their farm “the center of the world.” But until recently that nexus, though central due to its equatorial location, and essential as an economic engine to the surrounding community, was disconnected from the world at large.

“For us to be running a business selling globally, communication has always been a critical part of that,” says Tim Hobbs. “Malcom said he had some radios that could deliver broadband Internet. We said, ‘Let’s give this a try.’ We were the incubator point because we have an infrastructure here. And we’ve seen it grow over the past couple years.”

Maggie Hobbs still remembers having to drive eight miles to retrieve a single email. That’s changing with Mawingu — and it’s powerful, she says. “You can sit here, on the edge of Kenya, and have the same information presented to you as anywhere else.”

She adds that the effort is about more than just connecting the farm. “The Internet is important to everyone in the world. Kenya is no different. They may not have electricity, but the Internet is just as important.”

But Maggie emphasizes that connecting rural Kenyans is not a benevolent effort.

“We don’t look at Africa as a place that needs assistance; it’s about getting Africans up to speed in terms of tools. The word I would use is one of agency. You want to give the young people the idea that there is a hopeful future. And control over their own destination.”

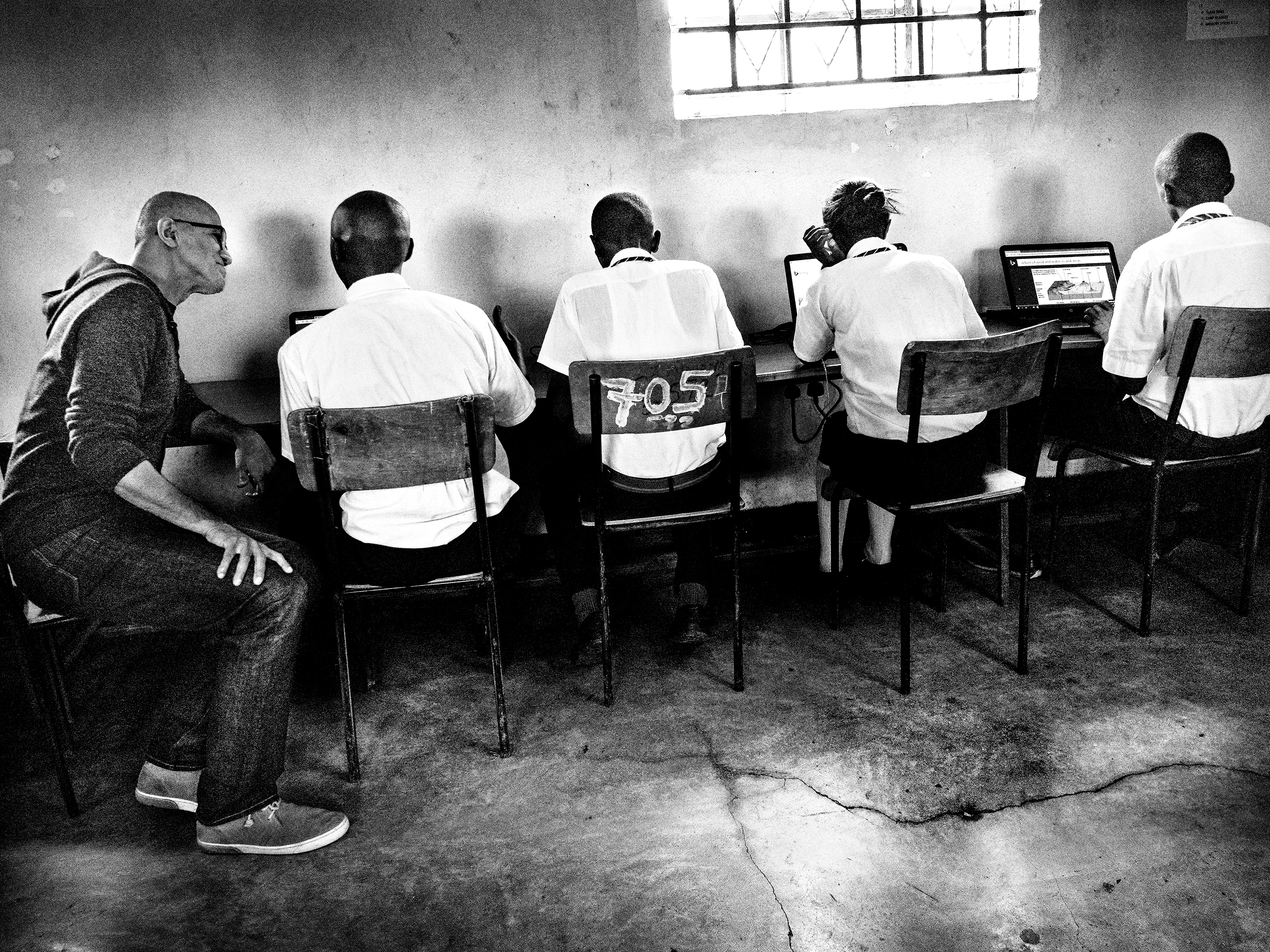

Benson Maina is one of those people. He runs Nanyuki’s Internet café, a 20-foot shipping container that boasts a half-dozen computers and a couple of laptops powered by solar panels, located on the outskirts of town.

Maina, who grew up in Nanyuki, says affordable access to the Internet is changing the community. “Mawingu brings information to society. It’s improved the lives of many,” he explains. “Without the Internet, it’s like living in darkness.”

On any given day, the café will be packed with everyone from children seeking education, to farmers looking for information, to entrepreneurs trying to earn a living online.

Chris Baraka rented a house near Maina’s Internet café and has spent the last year there, daily, doing online transcription, freelance writing and posting for social sites, where he gets paid based on the amount of readership.

Baraka, 23, is a former student in technology studies at Kenya’s University of Meru. Today, he earns enough online to make a living. But it’s more than just a job, he says. Mawingu, and the affordable Internet access in Nanyuki, have enabled him to achieve his dream of supporting himself without having to move back to Nairobi.

While there are other options for Internet in the area, it’s often unreliable coverage, based on a pre-paid system that’s cost prohibitive for most, he says, causing a classic conundrum: “You need to use the Internet to make money, but you can’t get online without having money.”

Baraka, a Windows 10 Insider, received his upgrade early. When Nadella visited the Solar Cyber, Wednesday, he was hard at work, writing.

Mawingu charges $1 for one week of unlimited access, $3 for a month. The average Kenyan earns $26 a week.

Now, Baraka is helping other would-be entrepreneurs achieve their dreams by showing them how to earn a living online.

“If you get the right people, I believe we have lots of them who are determined, who have the technology know-how to make money. If they can get this kind of employment in rural areas, they don’t have to keep going to Nairobi,” he explains. “Mawingu gives them a chance.”

This is particularly important in a country like Kenya, where more than 50 percent of the population is 18 years old or younger.

The availability of affordable Internet access is critical to keeping young people in rural areas, agrees Nanyuki Red Cross representative Kuria. “Before, if you wanted a good job, a better job, you had to go to a bigger town. Now people have opportunities. Here.”

The dream, says Maggie Hobbs, is that affordable, reliable Internet access will help enable a million people like Kuria and Baraka.

More broadly, the dream for TV white space technology, says Adaptrum’s Tang, is to connect the 4 billion people in the developing world who do not have Internet access today.

Microsoft-supported TV white spaces-enabled Internet is being used in 15 countries on five continents.

Along with its partners, Microsoft has helped deploy this technology to bring lifesaving, specialized medicine to women in Botswana; to rapidly deploy networks in response to natural disasters, such as in the Philippines and most recently in Nepal; to connect universities in Ghana and Tanzania; and to bring online three provincial areas and 28 schools in Namibia.

“We’ve seen this work on a small scale, here. Now we have an opportunity to work with Mawingu to see us scale up in a broader effort,” says Paul Garnett, a director of Affordable Access Initiatives at Microsoft. We’re in 12 places in Kenya now. We’ll be in a couple hundred more in a year or so.”

The TV white spaces effort is a natural outcropping of Microsoft’s origins, a company founded on the idea of democratizing technology. “Bill Gates had this crazy idea early on: a computer on every desk in every home,” Garnett explains. “The next frontier is how to get the world online.

“It’s a multiplier effect. The more of us who are connected, the more we all benefit.” (Watch video.)

Others are chasing this dream as well, be it through drones or weather balloons, though these technologies are yet unproven, Tang says. TV white space technology is more reliable and abundant, making it ideal for use in the developing world today.

“Utilizing the unused TV spectrum is an ideal solution in developing countries because it’s available and can travel long distances, up to 10 kilometers in any direction,” he says. “This is because of the frequency and the electromagnetic characterization. It’s useful in areas where people are spread out, where the population is sparse and there is a lack of infrastructure.”

Economist Thanki is still studying the long-term impact in Nanyuki, but so far he’s been surprised by how positive residents are when speaking about their increased Internet access. Over 95 percent thought it would lead to improvements in the community, and 92 percent thought it would lead to improvements in their personal circumstances.

“The idea that without Internet access today, you’re somehow apart from the global community seemed to really resonate,” he says.

“To a degree, access has become a right,” says Tang, adding that the Internet today is an indispensable part of people’s lives. “People in Africa and elsewhere in developing countries shouldn’t be deprived of that right. We believe it’s important, not just economically, but socially as well.”

“This is Malcom’s dream. It’s our dream. It’s the community’s dream,” says Maggie Hobbs. “It’s all coming together in this unlikely place, which is really where it needs to be the most. Because it’s going to change everything.”