AI and cloud combine to help protect vulnerable marine turtle populations in northern Australia and Cape York

There are only seven species of marine turtle on the planet. Sadly, six of them are now considered threatened with global extinction due to a combination of human, environmental and predator threats.

In Australia’s far north, Hawksbill, Flatback and Olive Ridley turtles come ashore on the beaches of western Cape York between June and November every year, females hauling themselves across the sand to dig nests and lay their eggs.

While turtle is one of many traditional food sources for coastal communities of Indigenous people, they have always been consumed at a sustainable level.

Until the 1800s, the biggest threat to Australia’s turtle population was predation on nests by dingoes and goannas. But again – even that was not a significant threat to the turtles.

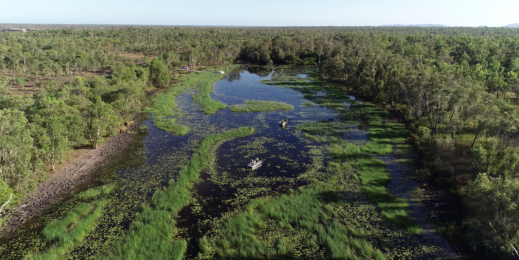

However, after pigs were introduced to Australia in the 1800s – and feral pig populations soared – turtles faced a much greater risk. The impact went largely undocumented on much of western Cape York until around 10 years ago when regional organisations and Traditional Owners raised the alarm.

Aak Puul Ngantam (APN) Cape York, a not for profit organisation belonging to Southern Wik Traditional Owners, has been working for a number of years on initiatives to protect turtles from predation that are sensitive to cultural, environmental and sustainable livelihood values.

Control methods have been able to reduce feral pig predation of turtle nests by as much as 90 per cent in the past. Management has been possible, but monitoring has been challenging – and without effective and timely monitoring, there is no way to assess the effectiveness of management initiatives.

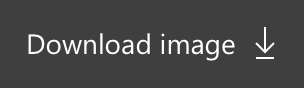

APN Cape York rangers face significant challenges monitoring turtle populations and nesting sites. Not only are the nesting sites very remote and spread across thousands of kilometres of coastline, they are virtually impossible to access during the wet season and for months afterwards, when the rangers have to cross waist-deep floodplains, often frequented by crocodiles.

All of this means that getting accurate, timely monitoring data has been so challenging and time consuming that the monitoring data has not been useful for supporting management activities.

Working together as part of an NESP Northern Australia Environmental Resources Hub project and under Microsoft’s AI for Earth program, APN Cape York, CSIRO and Microsoft have been using Indigenous knowledge, drone and helicopter-collected video, cloud computing and artificial intelligence to help identify turtle and predator tracks on remote beaches. Having more immediate and complete data will allow rangers, scientists and Indigenous leaders to work together on initiatives to more effectively manage nest predators and protect turtle populations.

Protecting turtle eggs from predators

The national science agency, CSIRO, and APN Cape York have been working together for around eight years on programs to protect vulnerable turtle populations. It is important work according to Indigenous APN ranger Dion Koomeeta.

“Most of the pigs are destroying our beaches, digging up all our turtle nests and other stuff as well. Normally they go round digging up all the nests. By the time we get down there, there’s not many eggs in a nest, it’s all dug up by the pigs,” says Koomeeta.

We use science to protect the turtles so our next generation can know what the turtles look like. It’s a good thing for the kids to learn the ranger stuff so when they grow up they can protect the land for the next generation to come.

According to Dr Justin Perry, CSIRO Research Scientist, “We built this from the ground up with rangers: it was an eight-year process before we started even thinking of technical solutions.

“There are three types of turtles that nest on western Cape York beaches. One is the Hawksbill, which is very rare on that coast. We’ve only found about a dozen of these turtles, in total, since we started monitoring.

“The two species we’re focusing on are the Olive Ridley and the Flatback turtles. Our biggest concern is the Olive Ridleys. Their nests are shallow and are generally laid on the beach rather than in the dune vegetation so they’re very exposed. Prior to targeted predator management 100 per cent of the nests surveyed on the accessible beach were destroyed by predation, with the main culprit being feral pigs.”

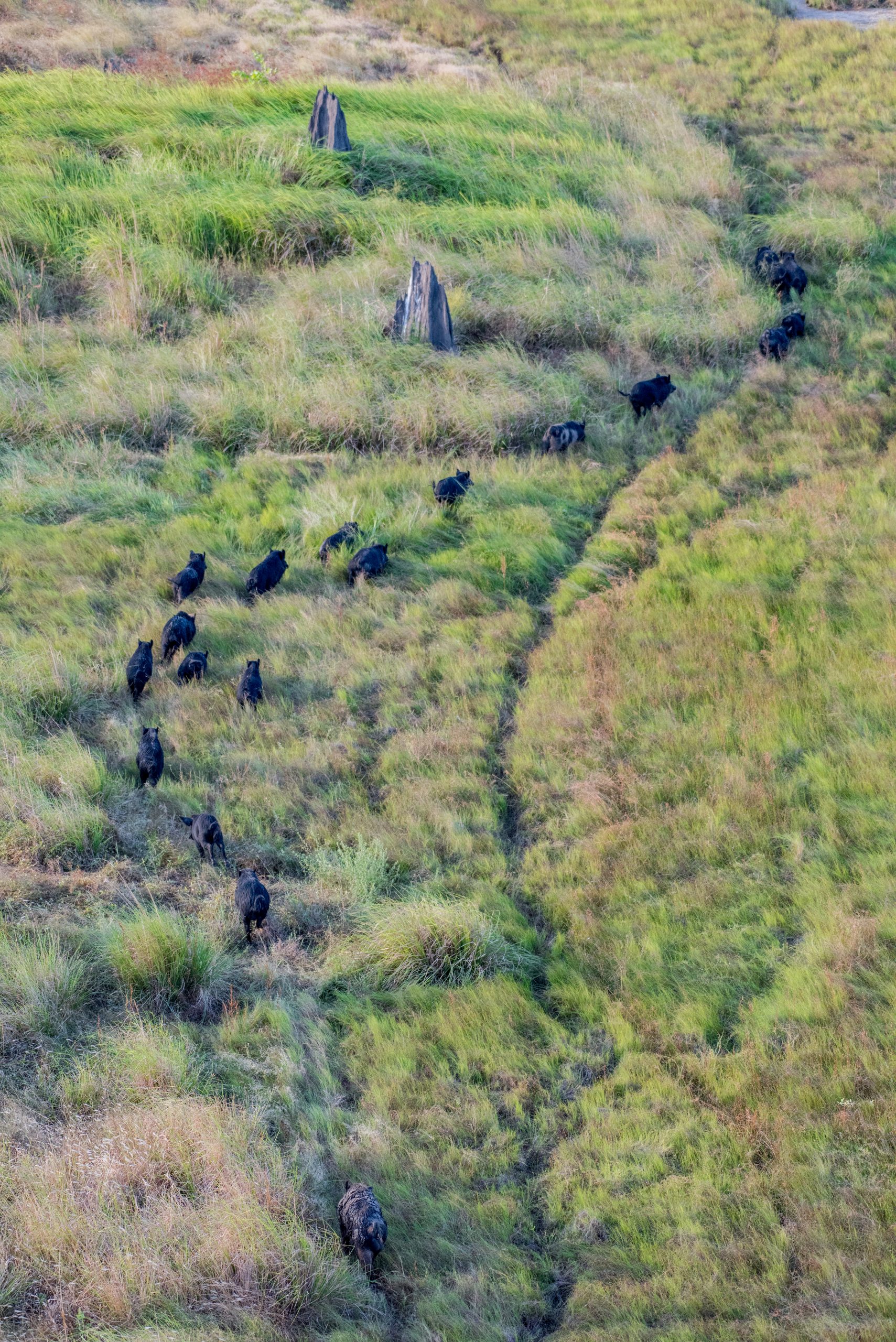

The main monitoring beach has around 350 individual nests laid per season, with around 80 surviving hatchlings per nest. CSIRO scientists say that typically about 100 nests would be subject to natural predation events, leaving 250 nests.

Once a baby turtle makes it into the ocean there are hundreds of ways it can die, which is why there are so many eggs laid – the more babies that make to the water the more chance that a handful will make it to adulthood.

The situation is of great concern to Wik Traditional Owners, who want to protect the turtles. The NESP Northern Australia Hub stepped in to support this long-term partnership between CSIRO and APN Cape York, so that Traditional Owners and scientists could come up with new and innovative ways to manage these predators together.

Using this research to target management activities has already reduced predation levels down to under 30 per cent which CSIRO and APN Cape York believe will safeguard a sustainable population of turtles.

To work out where to focus management efforts, scientists and rangers need to understand where the turtles are laying their nests, where their eggs are being eaten, and when predators are most active.

That is the first difficult task.

Aerial analytics

Access to the remote beaches of the far north can be very difficult, especially during and after the wet season – and there is only a limited window when turtles nest.

It can prove impossible to get to the turtle beach until late July or August after a wet season, when the waist deep, 100-metre wide floodplain is too boggy to traverse. That is long after the peak nesting period which begins in June. Rangers wanted to be able to monitor the beach earlier to protect the nests which are most vulnerable in the first few days after the eggs are laid – this is when the female turtle’s tracks are still visible to predators and when the scent of her freshly laid eggs is strongest. Then, there is a 50-day wait until the hatchlings start to emerge.

Ideally, rangers want to protect the nests in those first few days after nesting – but they also want to limit any physical visits to the area. The rangers also want to get fast access to this monitoring data, so they can quickly tailor their management actions to where new nests are located.

Being able to remotely monitor beaches using aerial footage addresses all three issues – as long as the images can be interpreted fast enough to be useful.

Aerial survey photographs from helicopters had been collected in the past, but required hours of painstaking analysis, limiting their usefulness from a management context.

To speed up the process, CSIRO approached Microsoft to see whether AI could help identify relevant information quickly from the tens of thousands of survey images, to pinpoint locations where there was evidence of both turtle nesting and predator activity.

Under Microsoft’s AI for Earth program, Microsoft engineers loaded the images to the Azure cloud, then developed a series of AI-infused image-detection algorithms, including a terrain classifier and a track/predator object detector. Both algorithms are showing early promise of detection accuracy, with the terrain classifier exhibiting a +90 per cent accuracy for distinguishing between beach, bush and ocean terrain, and the track/predator object detector incrementally improving its performance based on +45,000 further images processed and trained.

Improved environmental management

Kerri Woodcock, Biodiversity and Fire Program Manager for Cape York Natural Resource Management explains the scale of the problem, noting survey work from the early 2000s which revealed almost 100 per cent predation of turtle nests on the western Cape, which could have been occurring for two decades.

She acknowledged there would be no quick fix, because of the nature of the turtle lifecycle. “Some of them don’t reach breeding age until they are 30 years old, and then only one in 1,000 survives in the wild.”

However, she is heartened by the work now underway. “This is really an Indigenous-led threatened species program that’s having quantitative outcomes we can actually measure.”

She says the program provides rangers with important insights during peak turtle nesting season. “Rangers are monitoring not only the number of turtles that are coming in and laying, but also the amount of predation that’s happening and putting into place an adaptive predator control program to make sure that as many nests survive as they can.”

The initiative builds on the Healthy Country Partnership work already undertaken by Bininj co-researchers and Indigenous rangers, CSIRO, NESP, Kakadu National Park and Microsoft. Cloud computing and AI have been used in Kakadu National Park to monitor the spread of invasive weeds, providing insights to help Indigenous rangers manage the park and encourage the return of magpie geese.

The latest application of the technology demonstrates that the automation pipeline can be iterated and refined to address many different environmental challenges.

According to Perry, “We’re using Microsoft AI to automatically analyse tens of thousands of images for predator tracks and nest location, and sharing the insights with rangers in real time using a Power BI dashboard. We can now monitor twice the length of the coast line in two hours instead of a month.

This work has seen 20,000 hatchlings make it to the ocean every season. An entire ecosystem is being stabilised. New technology like AI is playing a vital role to bring turtles back from the brink of extinction.

In his opinion, “This work reflects the next step toward developing a flexible, adaptive management tool for environmental management.”

The turtle management system has been designed so that data input is simple – rangers simply take the SD card out of the drone or helicopter-mounted camera, upload that content to a folder, and the analysis is then automated.

The resulting analysis can then be fed into a dashboard, being developed by CSIRO and Microsoft using Power BI. This overlays data collected by rangers using the Nestor app on the ground with the insights collected from the analysis of aerial photographs to help rangers and scientists make decisions about how best to manage issues in a particular location at a specific time.

The dashboard shows the rangers where the turtles are, and where predation is taking place, in near real time.

The same insights are shared with Indigenous communities and Elders back in Aurukun to help them make decisions regarding local turtle populations.

Perry adds, “The more we can automate that monitoring process, the more the rangers can focus on actual management work. The whole reason monitoring exists is to inform adaptive management. But often we spend lots of time doing the monitoring, because it’s really hard work. So then you can end up just documenting the demise of a species.

“If we can make monitoring more efficient and targetted, that means more time can be spent on managing the threats. That’s really what gets you the important conservation outcomes. What we’re trying to do is get the appropriate information to the appropriate people in an appropriate timeframe. And then that allows on-ground management to become the priority, which is what the ranger programs are about.”

And for sea turtles that return to Cape York each year to lay their eggs, this delivers the best chance for their species’ ongoing survival.