Lost in translation – can AI keep endangered languages from disappearing?

Many Middle Eastern and African languages are disappearing, but technology is helping keep them alive

Seventy-eight-year-old Rashid Njapaa fears his ancestors are disappointed in him. Part of the Yaaku tribe in Kenya’s Rift Valley, Rashid is one of just seven people who still speaks the tribe’s native Yakunte language.

In an interview with Aljazeera, the tribesman said it was disturbing to see the young people of his community abandoning their mother tongue. And with all remaining speakers of the language now over the age of 70, it seems all the Yaaku can do is wait for the language of their ancestors to disappear completely.

They are not alone in their predicament. UNESCO estimates that a minority language disappears as often as every two weeks. At this rate, it’s predicted that as many as 90 percent of all endangered languages will be gone by the end of next century.

For the longest time, technology, which has enabled rapid globalisation, has been seen as a contributor to this problem. But the more we understand what is needed to help preserve endangered languages, the clearer it becomes that technology could be a critical part of the solution.

A region rich in diversity

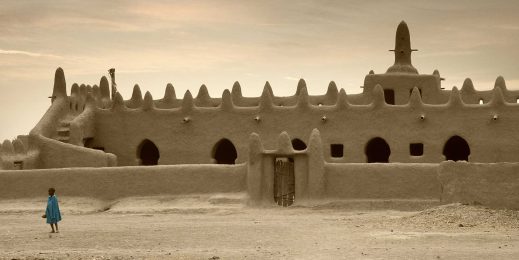

Few other regions across the world have more to lose from this decline in cultural diversity than the Middle East and Africa (MEA).

Many countries across the region score highly on Greenberg’s diversity index, meaning the probability of two people in the country speaking different languages to one another is good. While countries in other regions, such as the United States and United Kingdom, score 33 and 15 percent respectively, countries across MEA typically record much higher numbers from 71 percent in the UAE to 89 percent in Nigeria and 93 percent in Kenya.

In fact, Africa is the second most linguistically diverse continent in the world – home to more than 2,000 languages. For the people living in these countries, language is not just a form of communication, it’s a way to distinguish one’s identity.

Society is increasingly coming to realise how damaging this loss of diversity is to the broader population, particularly when it comes to achieving a holistic understanding of the world. British linguist David Crystal described the death of a language as losing, “a unique vision of what it means to be human”.

Communications specialists speculate that it’s not just our understanding of each other that we lose, but also rich sources of information about specific areas of the planet, and the plants and animals that live there. Experts believe the knock-on effect of loss of language could include everything from potential medicinal cures to management of marine and land resources.

Breathing life to languages

But inspired movements are proving that much can be done to put minority languages back on the map.

Fulbhe is one such language. Though spoken by an estimated 50 to 60 million people in 20 different African countries, the language had never been developed into a script.

For many this would have seemed an almost impossible situation – without a writing system, it’s difficult for people to record their history or even engage in the basic communications that facilitate daily activities.

Undaunted by this challenge, however, brothers Ibrahima and Abdoulaye Barry decided to create a Fulbhe alphabet, which is essentially how ADLaM or the ‘alphabet that will prevent a people from being lost’ came into being. They began by teaching the alphabet at local markets and then started transcribing books and producing ADLaM pamphlets.

Slowly but surely, ADLaM began to spread.

Now, for the first time ever, the Barry brothers have secured ADLaM support in the Windows 10 May 2019 update. It means users can type and see ADLaM in Windows, including Word and other Office apps – providing Fulbhe with a platform not only to survive, but to grow.

Adding minority languages to the applications used every day makes it easier for those languages to remain in use. This is why even seemingly small updates, such as Microsoft’s recent support for the addition of a Frisian spell checker to its office software, can make a massive difference to the preservation of endangered languages. Frisian, a cousin of the English language that goes back at least 1,400 years, is making a comeback in the Netherlands. Though spoken by around just 500,000 people, it’s hoped that through ongoing community efforts, the language may yet have a fighting chance.

AI is a game-changer

In many ways, technology has provided a critical lifeline to endangered languages for some time. In fact, the ability to record speakers, transcribe text and then develop databases of sharable information has proven invaluable.

But even with this digital capability, the manpower required to record and process the volume of information necessary to preserve a language is enormous.

This is where AI can make an unmatched impact. Not only is the technology able to store and process data at incredible speeds, it’s also able to identify patterns and create new ones.

Already, AI is making endangered languages more accessible by bridging the translation gap between these languages and the rest of the world. Microsoft Translator Hub, for example, is a powerful tool that enables organisations and communities to customise Microsoft Translator’s neural text and speech translation systems to create their own unique translation tools.

In Mexico, the Universidad Intercultural Maya de Quintana Roo is making use of the Hub to record and share languages such as Yucatec Maya, a minority language descended from the ancient Mayan empire. Similar efforts are being made to preserve Querétaro Otomi, another language indigenous to Mexico that is under serious threat.

“To make sure this model can be repeated for other languages, the hub has been developed in such a way that it is web accessible anywhere in the world,” explains Mike Yeh, Head of Microsoft’s Corporate, External and Legal Affairs in MEA. “This means under-resourced communities and organisations all over the globe are able to take advantage of the offering in order to help preserve their language.”

What will it take to turn the tide?

Futurist, Thomas Frey, predicted that eventually AI will become the foundation for an AI Language Recreation Engine that draws on a global language archive to generate a three-dimensional avatar capable of teaching any language to a prospective student.

It’s a prediction that may be less futuristic than people might imagine. At a recent event in Las Vegas, Microsoft Corporate Vice President Julia White delivered a HoloLens demonstration that took the show by storm. Drawing on AI technology, Microsoft produced a photorealistic hologram of White who then continued the keynote in Japanese, a language that she doesn’t speak.

Witnessing the disruptive potential of AI, it’s easy to imagine a future in which languages are not reliant on native speakers to live on.

Key to unlocking this future is the realisation that technology alone will not prevent further casualties. “Preserving an entire language takes whole communities of determined people with the will to turn the tide. Microsoft is partnering with individuals and organisations around the world that are pursuing the preservation of cultural heritage,” says Yeh.

“MEA being this diverse is a significant advantage for both business and society. Helping to preserve the languages that form the backbone of that diversity is a critical undertaking, and one which we simply can’t ignore,” concludes Yeh.

![A security team analyses key data from a visual dashboard.]](https://news.microsoft.com/wp-content/uploads/prod/sites/133/2023/04/Security-Sprint_TL_Banner-Image-519x260.jpg)