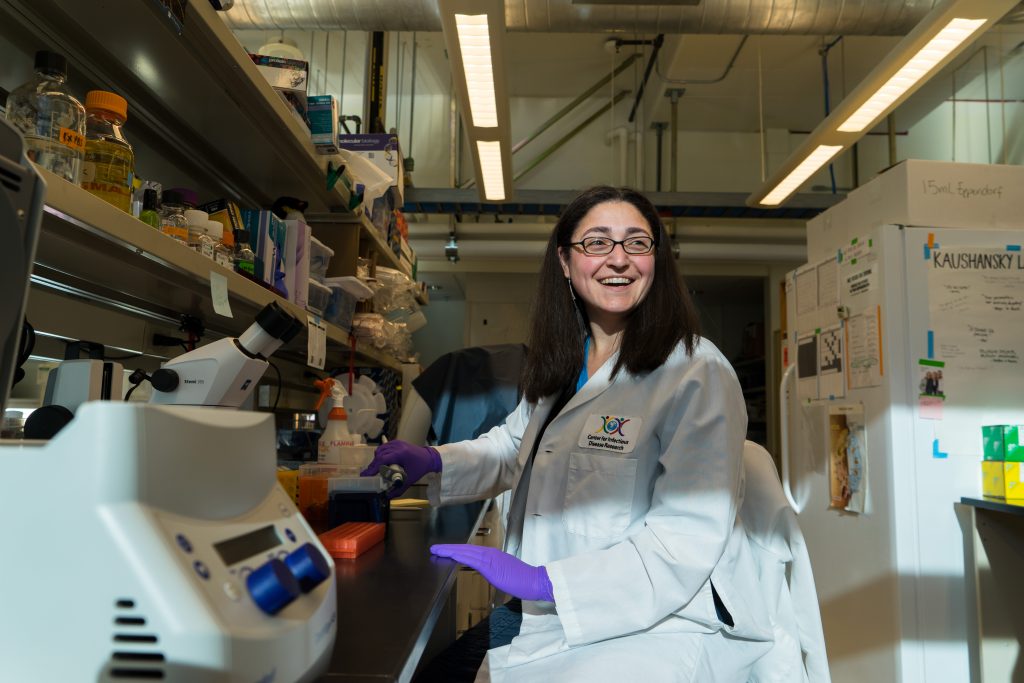

Alexis Kaushansky: Malaria research as a form of social justice

It was 2:30 a.m. and Alexis Kaushansky was alone in her lab. All was quiet except for thousands of mosquitoes buzzing in the insectaries, housed in a warm, humid breeding area known as the “swamp room.” She had been working around the clock on a malaria experiment.

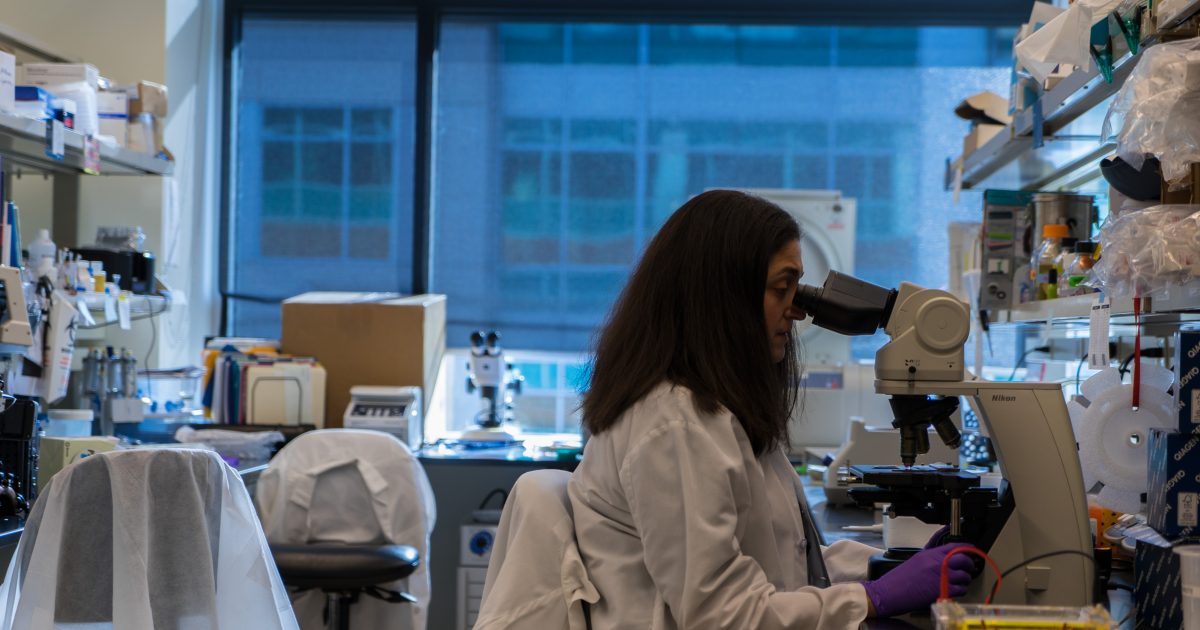

Finally it was time to check the results. She peered into a microscope and couldn’t believe her eyes. Almost all the parasites she was testing had died, but it would be hours before she could tell anyone the news. Instead of going home to sleep, she excitedly ran back to the insectary to redo the study and confirm her first major breakthrough: that malaria-infected liver cells have similar features to early cancer cells. Her 2011 research, published a few years later, paved the way for studying cancer drugs to help eradicate malaria.

“It’s a true discovery doing science,” says Kaushansky, a malaria researcher at the Center for Infectious Disease Research in Seattle, the largest independent nonprofit in the U.S. focused solely on infectious disease research.

“I love everything about it. I love experimental design, I love going into the lab to do the experiment, I love troubleshooting, I love trying to make sense of it all. I love how interdisciplinary it is. It never gets old to me to make discoveries about things that are important to people all over the world.”

Infectious diseases kill more than 14 million people a year worldwide. A great many of those people are poor, and Kaushansky’s work is an extension of her passion for social justice. She and the Center are using new approaches in advancing drugs and vaccines to reduce the disproportionate effect of infectious diseases on low-resource areas.

“This is one of the major ways that inequity around the globe is propagated,” Kaushansky says.

Empowering her passion and goals are Microsoft tools for efficiency and collaboration. Malaria research has traditionally focused just on the malaria parasite, but Kaushansky is studying how the parasite infects its host, in which she uses Excel for first-pass data analyses. Her work is opening up malaria research to different kinds of drug development to prevent the disease.

The Center grows tens of thousands of Anopheles mosquitoes a week with an intricate, important schedule. ‘Our mosquitoes have their own Outlook calendar!’ Kaushansky says.

In another study published last year, Kaushansky and her colleagues identified a receptor that the malaria parasite uses to invade liver cells, another key insight in understanding malaria’s parasite-host interface.

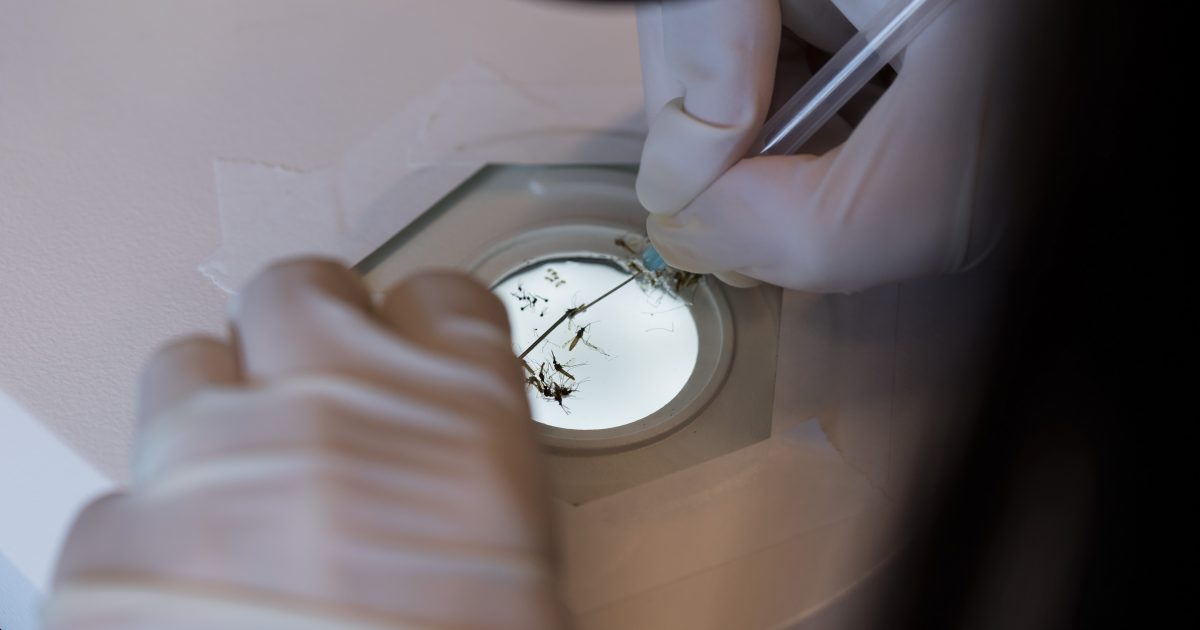

“We know that if a mosquito has malaria parasites in the salivary gland, and it spits those parasites onto the table, those parasites will die within minutes and won’t ever infect a person or cause disease,” she says. “And same thing if the parasite just goes into the skin and hangs out there for a day: no disease.”

But if the parasite enters the liver, its initial target organ, it can cause malaria’s fever, chills, sickness and death.

“We really believe the [parasite-host] interface is going to tell us the most about what’s going on and lead to cures and prevention,” says Kaushansky.

The collaborative nature of her field means she works with people worldwide and across disciplines, including engineers, physicists and other biologists. She uses Outlook to sync and organize meetings, calendars and schedules, and Skype to work with researchers from California to Boston to Thailand.

“Science is both a national and international endeavor, so we have collaborators all over the place and we use Skype. That’s definitely helpful,” says Kaushansky, who also uses Skype to interview potential hires.

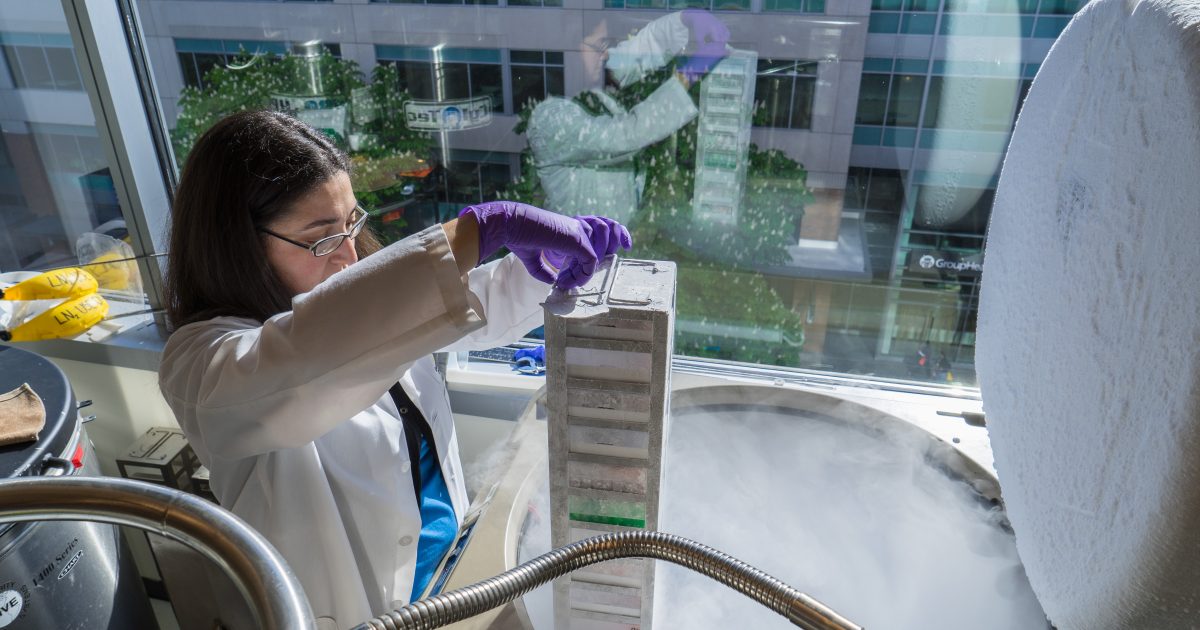

A hurdle in malaria research is studying the parasite when it infects a host, but before it causes symptoms, a tough window filled with technical challenges. To meet them, the Center grows tens of thousands of Anopheles mosquitoes a week with an intricate schedule. Kaushansky’s lab uses Outlook to manage many different calendars, but the mosquitoes’ calendar is the most important one, she says.

“Our mosquitoes have their own Outlook calendar!” Kaushansky says.

It starts with a blood meal and continues when the females lay eggs, the eggs become pupae and the pupae are moved to smaller cages. They grow into adults, get infected with various malaria strains and serve as hosts for the parasite to develop. Then Kaushansky and her colleagues hand-dissect the mosquitoes’ salivary glands to extract the parasites for different studies. The cycle takes four to five weeks.

“We’re running all these different things in parallel. That’s why it’s the most important calendar. If I miss a meeting, nothing will happen. But if the mosquitoes don’t get infected at the right time, all science shuts down for weeks on end,” says Kaushansky with a laugh.

She’s only semi-joking. Her study of host factors and cancer drugs opens up malaria research to the vast field of cancer science and its cutting-edge technologies. The potential to help millions of malaria patients, who on average live on $2 a day, is huge. Before becoming a scientist, Kaushansky had worked in politics to make the world a better place — a passion that continues today.

“I ended up working on malaria because I felt the technology we’ve developed could make a big impact,” she says. “I really wanted to be in an environment and a field where I thought I could make a big difference.”

To see more on Kaushanksy, check out Microsoft’s Facebook, Instagram and Tumblr pages.