Medical student James E.K. Hildreth was on his first clinical rotation when he saw the patient, a Black woman in her early 20s who had just given birth. It was the early 1980s and AIDS was spreading, with no treatment for the virus. Both the mother and her baby did not make it.

“There was nothing we could do except treat their symptoms and watch them die,” Dr. Hildreth says quietly. The experience so affected him he changed his specialty from training to be a transplant surgeon to an HIV investigator. He became one of the world’s top HIV/AIDS researchers, with much of his work focusing on blocking HIV infection by learning how it gets into cells.

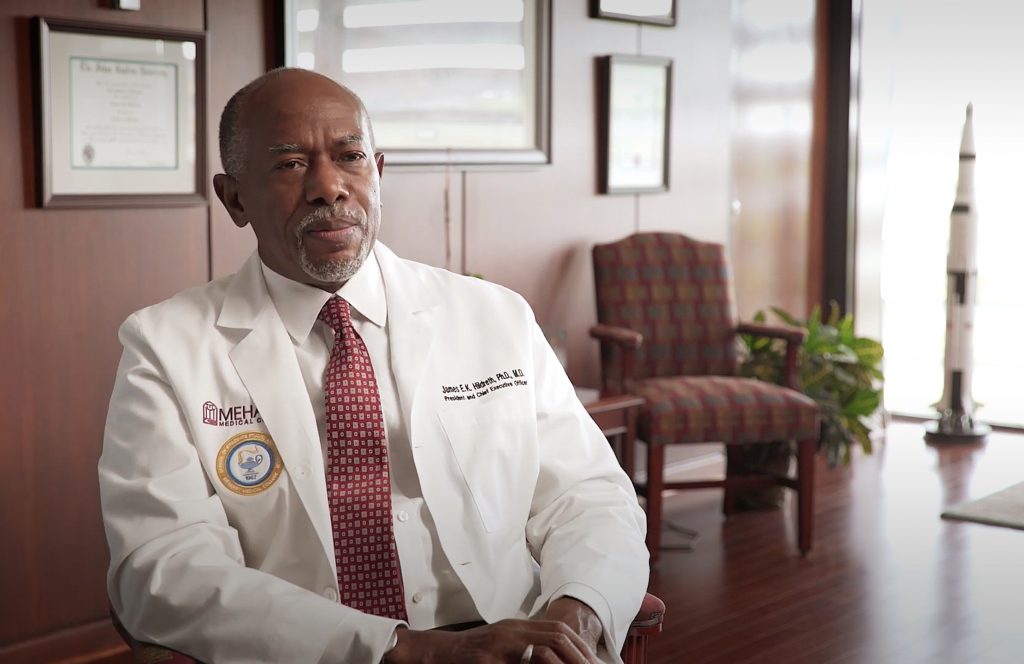

Now, as president and CEO of Meharry Medical College in Nashville, one of the nation’s oldest and largest historically Black academic health science centers, he sees similarities between the AIDS era and the COVID-19 pandemic responses – initial reluctance by some government officials to acknowledge the gravity of the virus and its impact on people of color – and says they must not be repeated.

Dr. James E.K. Hildreth, president and CEO of Meharry Medical College in Nashville. (Photo courtesy of Meharry Medical College)

“There’s a lot that we learned,” Dr. Hildreth says. “But one thing we learned for sure is that we need to do a better job of diversifying our health care work force. We need to spend more money on public health and preventive medicine to prevent this from happening again. And it also illustrates the importance of improving the basic health status of all of us, so that the next time this happens, we won’t be having the same conversation again. This is not the last pandemic for sure.”

Meharry is among the academic institutions and nonprofit organizations that are grantees of Microsoft AI for Health, which uses artificial intelligence (AI) and Azure high-performance computing to help improve the health of people and communities worldwide. AI for Health was launched a few months before COVID-19, and once the pandemic struck, more than 180 AI for Health grants went to those on the front lines of COVID-19 research, data and insights.

John Kahan, Microsoft vice president, Chief Data Analytics Officer and global lead for the AI for Health program, says when the pandemic started, so little information was known, and there was a massive race for data and insights.

John Kahan, Microsoft vice president, Chief Data Analytics Officer and global lead for the AI for Health program.

“I think that our learning is in better shape now,” he says. “The science is in better shape. But it is still unclear that the governments of the world have gotten together on a common set of standards” around exactly what data must be gathered immediately after a pandemic has been declared.

Other AI for Health grantees, including Brown University School of Public Health, the Institute for Health Metrics and Morehouse School of Medicine, agree about the work that remains to be done.

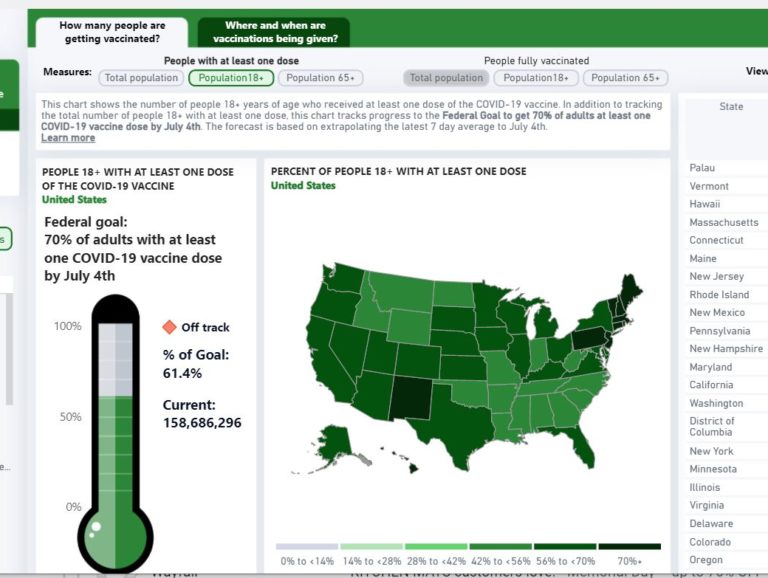

Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, is a pandemic expert who now is also a familiar face to many television viewers in the U.S. for his perspectives. Using Azure and Power BI, Brown and Microsoft AI for Health developed a comprehensive COVID-19 dashboard that includes whether states in the U.S. are meeting COVID-19 testing target numbers, risk levels for each county in the country, and vaccine distribution and administration data. The dashboard also includes worldwide figures, and has become a helpful tool for the public, as well as for policymakers and leaders, to gauge the progress of the vaccine rollout.

Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health. (Photo courtesy of Brown University)

What’s important about it and other COVID-19-related dashboards that have since been created is that they represent the first time such important tools have become widely available.

“Fundamentally the public health system’s data infrastructure (during COVID-19) sort of worked a little, but not nearly enough,” Dr. Jha says.

“Every public health department in the U.S. has its own data infrastructure for collecting information on infections, tests, hospitalizations and deaths – and they’re really, really old, clunky systems,” Dr. Jha says. “What that means is that there are places across the country when somebody has a positive COVID-19 test, they might send that information to their local health department by literally printing out the test result, and faxing it to the local health department, who will then hand-enter it into a computer system. This is how data is still largely being collected.”

It hindered the COVID-19 response in the U.S., Dr. Jha says. “At a national level, until very recently, we had no government-driven data on infections and cases and deaths. In fact, national data was being aggregated by a group of journalists who were pulling together data and cleaning it up across every state and putting it together. Even the previous White House (administration) was largely using this data as opposed to using federal data.”

Dr. Jha says a collection of anonymized, non-health related data – such as restaurant reservations made through an app – also are “incredibly helpful” in providing information about people’s behaviors during the pandemic, such as their willingness to go out for dinner. “It’s really a way of measuring people’s sense of safety in their community,” he says. “For example, we saw reservation numbers fall as infection numbers began to rise, well before any policy was made on shutting down restaurants.”

The government didn’t start releasing hospital data until about November 2020 in the U.S., and it’s still not available in many, many countries around the world.

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington School of Medicine used similar anonymized data collected through social media platforms to learn more about behaviors.

At the start of COVID-19, IHME began creating forecasts for COVID-19 cases and the resulting hospital bed demand in the university’s health systems, which proved successful and sparked requests from states across the U.S. and countries around the world. The AI for Health data science team, in roughly 72 hours, rapidly built new Azure capabilities and migrated the IHME data into it to meet the expected onslaught of demand worldwide.

“We produced forecasts for every state in the U.S., put them out publicly on March 26, and then that just created a huge flood of further requests,” says Dr. Christopher J.L. Murray, chair of the department of Health Metrics Sciences at UW and director of IHME. “We rapidly expanded from forecasts for the U.S. to adding Europe and Latin America, and then Africa and Asia. By the summer of last year, we were producing forecasts on a weekly basis for every country.”

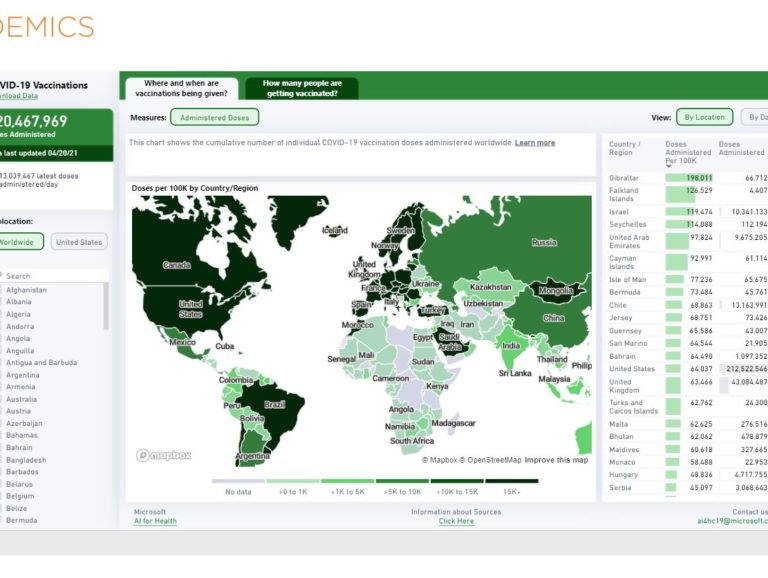

Brown University example of a dashboard from April 2021 showing the number of COVID-19 vaccinations worldwide at that time.

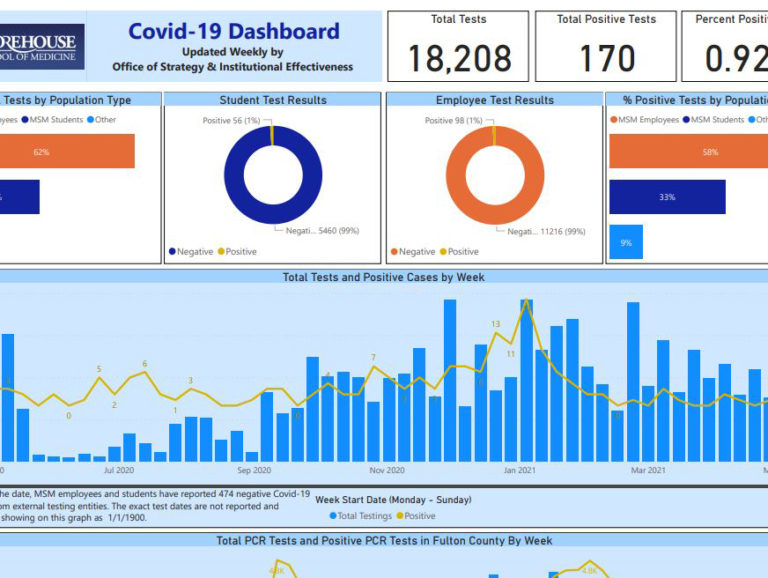

Part of a recent Morehouse School of Medicine dashboard showing COVID-19 test results for students and employees, and positivity rates. (Photo courtesy of Morehouse School of Medicine)

Brown University dashboard from late May 2021 showing COVID-19 vaccination rates in the United States.

IHME also started releasing expanded COVID-19 data visualizations and forecasts – including cumulative and daily deaths, hospital bed use and daily infections and testing – that the White House, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, state governors and hospital administrators have started using to mobilize resources.

Dr. Murray says it’s crucial to have hospital data available.

“It’s a more standardized measure than numbers of cases,” he says. “We learned over the course of the pandemic how bad many of the data systems are in reporting cases and deaths…there’s all sorts of biases based on access to testing, in some cases based on politics.

Dr. Christopher J.L. Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. (Photo courtesy of University of Washington)

“The government didn’t start releasing hospital data until about November 2020 in the U.S., and it’s still not available in many, many countries around the world. That really limits our ability to track and forecast the pandemic.”

At Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM), a historically Black medical school in Atlanta, while the leadership of the institution made it a point to hold weekly virtual town halls to communicate with students and staff about COVID-19 and regularly test for the virus, they also developed a “Return to School” application to further ensure the safe return of students, faculty and staff to campus. The application is also used across the Atlanta University Center Consortium (AUCC) campuses that include Morehouse College, Spelman College and Clark Atlanta University.

The web-accessible program works on digital devices such as mobile devices or computers and uses Microsoft AI, Azure and Microsoft Power BI resources to help provide a big-picture look at the campus’ overall health.

With the “Return to School” application, each person must complete a “daily symptom tracker” and show the output at the entrance to campus every time before they are allowed to come onto the campus grounds. Sample questions in the tracker include the following: Are you coughing? Sneezing? Did you travel somewhere in the last 21 days? Any “yes” answers serve as a red flag and yields a “red pass.”

The “Return to School” program has been an effective way of to allow students, faculty and staff back on campus, says Dr. Alexander Quarshie of Morehouse School of Medicine. (Photo by DV Photo Video)

Any person with a “red pass” on the “Return to School” application will not be admitted to campus, says Dr. Alexander Quarshie, a professor of Community Health and Preventive Medicine at Morehouse School of Medicine, who worked with the MSM, AUCC and Microsoft AI teams on “Return to School” application.

Those who are given red passes are sent to the school’s student services or human resources offices for follow-up to be tested for COVID-19, and if they test positively, are directed to follow the CDC’s isolation protocols.

“But if persons are able to truthfully complete these symptom tracker questions, and they also comply with the school’s COVID-19-testing protocol, then they are issued green passes,” he says. “It has been a very effective way of making sure that only those that are compliant, and only those that are safe, can return to campus.”

Meharry Medical College is using AI tools to identify COVID-19 hot spots, analyze mental health impacts and build mobile apps to address behavioral needs, as well as to predict health outcomes for minority communities.

Among the AI tools is a precision population health approach that transcends longstanding gaps by providing what is known as social determinants of health (SDOH)-tailored and equitable healthcare.

We need to spend more money on public health and preventive medicine to prevent this from happening again.

Dr. Hildreth was a member of the Food and Drug Administration committee that authorized the first two COVID vaccines. Earlier this year, he was named one of 12 members of the Biden-Harris COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force, which will be making recommendations on how to address the health inequities caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and how to prevent such inequities in the future.

‘The first lesson for me is the importance of listening to experts and scientists when you’re dealing with a public health crisis as caused by a virus or a pathogen,” he says. “We spent decades and decades understanding the biology of viruses and pathogenic organisms, and not to take advantage of that knowledge was very unfortunate.

“What we should have done was to focus on those more vulnerable to save as many lives as possible – people in assisted-living facilities, people of color and Indigenous people,” Dr. Hildreth says. “If we had focused our attention on the most vulnerable in terms of our prevention strategies, hundreds of thousands of people in our country would still be alive today.”

With Black doctors totaling less than 6% of physicians in the country, the U.S. also needs to do a better job of diversifying its public health force, he says.

“We need to spend more money on public health and preventive medicine to prevent this from happening again. And it also illustrates the importance of improving the basic health status of all of us, so that the next time (a pandemic) happens, we won’t be having the same conversation again.”

Q&A: Peter Lee on the COVID-19 pandemic, societal resilience and crisis-response science

Learn about resilience through innovation

Lead image: Faculty, staff and students are checked for COVID-19 symptoms at the entrances to Morehouse School of Medicine using the “Return to School” program on their mobile devices. (Photo by DV Photo Video)