You may not know Eugene Flaherty, an IT expert in Massachusetts who loves science fiction and has cerebral palsy, or Anne McQuade, a former software tester in Georgia who runs two book clubs and has low vision. Maybe you don’t know anyone who has called the Microsoft Disability Answer Desk or is known as a “Trusted Tester.”

But they’re among the thousands who helped shape technology you probably use every day. Their voices and work are vital to Microsoft’s behind-the-scenes system of building technology that works for many millions of people with and without disabilities.

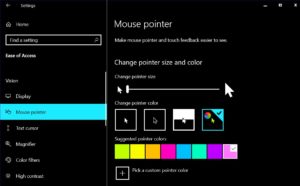

If you’ve ever increased your mouse pointer size, you have McQuade’s experience to thank. If you use Narrator, a screen reader in Windows that reads text and buttons aloud, it was Disability Answer Desk customers who are blind or have low vision who suggested the idea for Narrator Home, a feature that makes the screen reader easier to use. And if you dictate messages on your device, it’s people like Flaherty who bolster research that helps it recognize what you say.

“It is important for me as a member of the disability community to have a voice, because we can help improve things for everyone. And technology can do nothing but good things for the disability community,” says Flaherty, who uses a power wheelchair and keyboard shortcuts and has shared his experiences with dexterity and speech recognition with Microsoft.

The company’s advances in accessible technology stem from an evolution model that includes thousands of tests, surveys, reviews and conversations with people with disabilities — guided by an emphasis on inclusive participation and the phrase “nothing about us, without us.”

Anything I can do to make a product better and help somebody else be more productive is the right thing to do.

The approach to product testing revolves around three key programs: the Accessibility User Research Collective (AURC), a community of people with disabilities who give feedback to Microsoft; Disability Answer Desk, a free 24/7 support team that solves problems for customers with disabilities and passes their feature ideas to product teams; and the Department of Homeland Security Trusted Tester program, which trains and certifies accessibility testers.

“These programs help build trust with the disability community, which is foundational to maintaining credibility and creating better products and experiences,” says Megan Lawrence, Microsoft senior accessibility evangelist.

“We have built a scalable system that brings the voice of people with disabilities into our company, better understands how they use our products and provides feedback to engineers to make our tools more accessible. We’re sharing how we do this to help others, and we’re constantly learning.”

A community of more than 900 people with disabilities, the AURC is managed by Shepherd Center researchers who organize diverse, targeted cohorts for Microsoft design and engineering research. Separate from the AURC, Shepherd Center is a rehabilitation hospital in Atlanta for people with spinal cord and brain injury and other neuromuscular conditions. Research participants do not need to be hospital patients.

“The overall goal is to help bring technology to all different types of people with all different disabilities,” says AURC operations director Nicole Thompson. “Accessible technology gives people the chance to be independent and do the things they love and want to do.”

This year, more than 500 members, who include Flaherty and McQuade, have shared their experiences with engineers. In the last three years, AURC members, who earn $50 an hour for their research participation, have contributed feedback to roughly 75 projects that led to new and improved products and features. Research with McQuade and other members has led to improvements to Windows Ease of Access features like pointer sizing, text sizing and high-contrast color mode.

“Anne regularly gives fantastic feedback,” says Windows accessibility leader Jeff Petty. “When you have a person with a disability who can share their story and articulate why they love using bigger text, it helps us connect with their experience and understand the importance of building better features.”

For McQuade, a former telecommunications software tester, working with the AURC and Microsoft makes her feel good about using her tech skills to help others. She had to leave her job six years ago when her vision deteriorated from retinal dystrophy and now works as a disability advocate.

“One of the hardest parts when I stopped working is that I felt I lost my purpose,” McQuade says. “It feels great to be asked now for my input. It makes me feel confident.”

While the AURC supports targeted user research, Disability Answer Desk provides a big picture of what customers want. The live, global tech support service for customers with disabilities fields 150,000 inquiries a year, but the broader work involves listening to customer stories and identifying opportunity areas.

“Not only do we want to solve your issue in the moment, we want to understand what we can do to make better products,” says Neil Barnett, director of accessibility and inclusive hiring at Microsoft. “So we have systems in place to drive that feedback into engineer groups.”

To provide quick access in their own language, Disability Answer Desk agents can provide direct video support in American Sign Language instead of using a video interpreting relay service. They also partner with the mobile app Be My Eyes for customers who are blind or have low vision, which allows agents to see a customer’s screen or device through the app and the customer’s camera phone.

The service has been so successful that Microsoft helped Google and others start their own disability support services and work with Be My Eyes last year. This year, the Disability Answer Desk team published an industry playbook to help more organizations start their own support desks for customers with disabilities.

“We’re sharing our learnings because we see it as a valuable way to accelerate efforts across industry and power up the disability community,” Barnett says. “And we want to see more companies invest in accessibility.” Learnings include the playbook, webinars and product training opportunities for customers.

It is important for me as a member of the disability community to have a voice, because we can help improve things for everyone.

The third prong of the company’s testing approach leans on recognized accessibility standards. In 2010, two employees with Department of Homeland Security — one who was blind and both experts in accessible technology — created a program called Trusted Tester, which trains and certifies people to test software for conformance with federal procurement standards. The program has created a skilled, global workforce of nearly 2,500 Trusted Testers who evaluate products before release.

“Accessibility should never be a barrier,” says Cynthia Clinton-Brown, director of Office of Accessible Systems & Technology, which is a part of DHS. “By making it easier for developers and content creators to develop and maintain accessible products, end users will have access to products and services that are accessible when released.”

Microsoft was one of the first companies to partner with the program about five years ago, helping it expand and increase the number of certified testers. The program provides a foundation for efficient, large-scale testing, with more than 800 Trusted Testers who have been affiliated with the company over the course of the partnership. Their evaluations are used in Microsoft accessibility conformance reports for products and services.

“Trusted Tester builds a new level of trust in the accessibility of our products and elevates the quality of experiences for people with disabilities across our products and services,” says Clint Covington, Microsoft group program manager of entertainment and devices accessibility.

The approach has come a long way in the 12 years that Jason Grieves worked as a Windows manager. Grieves, who has low vision, got a clear lesson on the value of bringing in testers early in the software cycle after pouring a lot of effort into an accessibility feature. He thought the feature was good because it worked for him, but a colleague who was blind tried it out — and it didn’t work at all.

“Fast forward to now, and teams are eager to design and code products to be accessible from the start,” says Grieves, whose role for the past decade involved meeting regularly with disability communities and practicing the inclusive principle of “designing for one and extending to many.”

Example: Pointer colors. A member of Microsoft’s low-vision advisory board had said he often lost his mouse pointer “in a sea of white and black,” prompting Grieves’ team to build a feature for him to choose one of several bright pointer colors that were easier to see.

When Windows Insiders, who test Windows updates, looked at the feature, they thought the limited colors were nice, but wanted to pick their own. What began as an accessible feature for one person has now become a custom color picker beloved by many people, from sports fans designing their pointers in favorite team colors to Grieves’ young son, Tommy, who always chooses the color pink.

“It’s a fantastic example of inclusive design,” says Grieves.

For John McKeown, a database engineer in Virginia with low vision and a member of the AURC, the chance to help design tools used by many people is gratifying — especially given the importance of assistive technology in his own life.

“To provide feedback that may go all the way to developers and manifest in an improved product for thousands of people around the world — that’s a powerful thing,” says McKeown, who has done surveys for Microsoft.

“Anything I can do to make a product better and help somebody else be more productive,” he says, “is the right thing to do.”

Lead image: Eugene Flaherty (photo courtesy of Flaherty)