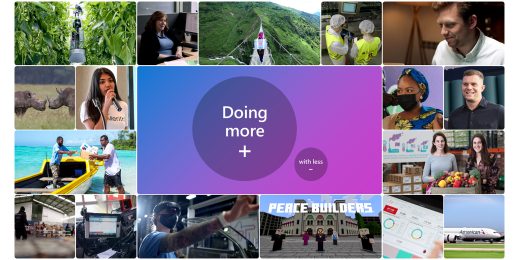

Kids get ‘eye-opening’ classroom lessons through video calls that span millions of miles

Shiva Kumar teaches in the sweltering farmlands of southern India, but when he wants his students to learn about other cultures, empathy or even the foreign concept of being freezing cold, he whisks them to exotic locations at the ends of the earth.

Kumar’s students have traveled millions of miles around the world, virtually, through the Skype sessions he began arranging in 2015. And after more than a thousand interactions with classrooms or experts in dozens of countries, he’s still amazed by the surprising lessons learned.

Take the time his class of 8- to 10-year-olds had a video call with kids in a Kenyan refugee camp.

“We found out that six kids were sharing one textbook there, and my students were shocked to learn of the difficulties they have and yet see the empathy flowing among them despite it all,” Kumar recalls. “My students realized there are a lot of poor people in the world, and it inspired them to start sharing more amongst themselves. Even small things like lunch, or a pencil or eraser, or sports equipment — they began sharing everything.”

For this year’s Skype-a-Thon, an annual event to be held Nov. 13 and 14, the students in Kumar’s 10 science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) classes will bring their sleeping bags to school so they can do eight-hour shifts of 30-minute Skype sessions. The two-day marathon of virtual travel has become a staple for Kumar’s classes ever since the first one four years ago, when the students’ connections with classrooms around the world spanned more than a million miles. The kids decorate their school with lights and showcase their Indian culture through traditional dances and musical instruments, as well as modern STEM projects.

Last year, almost half a million students from more than 90 countries participated, traveling 14.5 million miles. The goal is to meet or exceed those figures this year.

And this year, the students’ efforts will provide a tangible benefit. For every 400 miles virtually traveled in the Skype-a-Thon, Microsoft will donate the resources for a student to attend school in one of the nine WE Villages in Asia, Africa and Latin America, with a goal of helping 35,000 kids. The WE Villages international development model is part of WE, an organization that also includes WE Schools, which focuses on empowering kids to create change locally and globally.

“Children helping children through education – that’s how our mission to ‘make doing good doable’ started out,” says Erin Barton, chief development officer for WE. “We’ve got youth who are privileged enough to have access to technology, and now they’re giving the opportunity to others to have access to gain an education themselves.”

Kumar was Asia’s first “Skype master teacher,” a designation for volunteers who use Skype often in their lessons and are willing to train other teachers in how to use it to connect their classrooms. The Microsoft Educator Community is a free site where hundreds of thousands of teachers share lesson plans and offer themselves – and their classrooms – up for connection opportunities, such as educational games and contests.

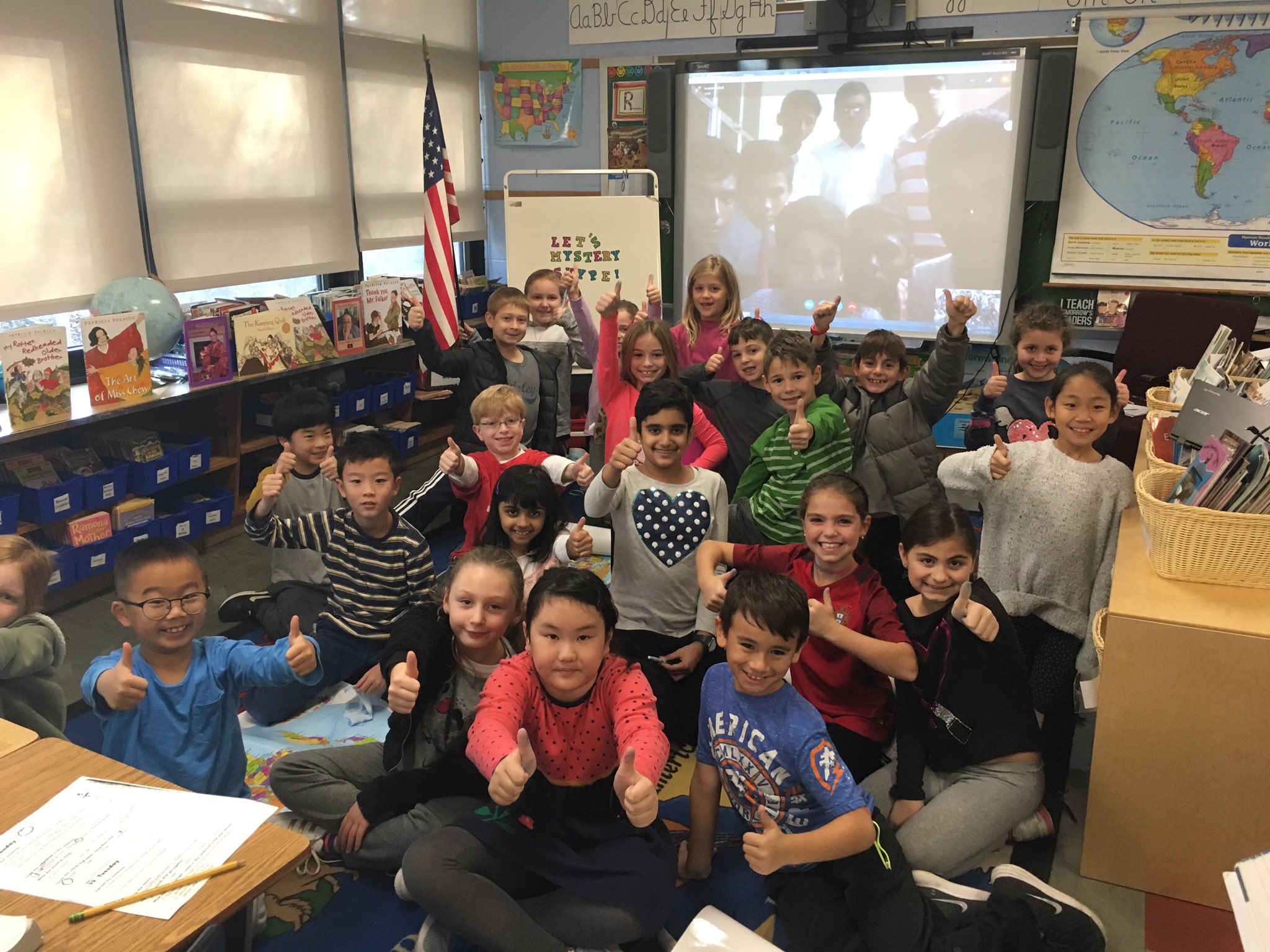

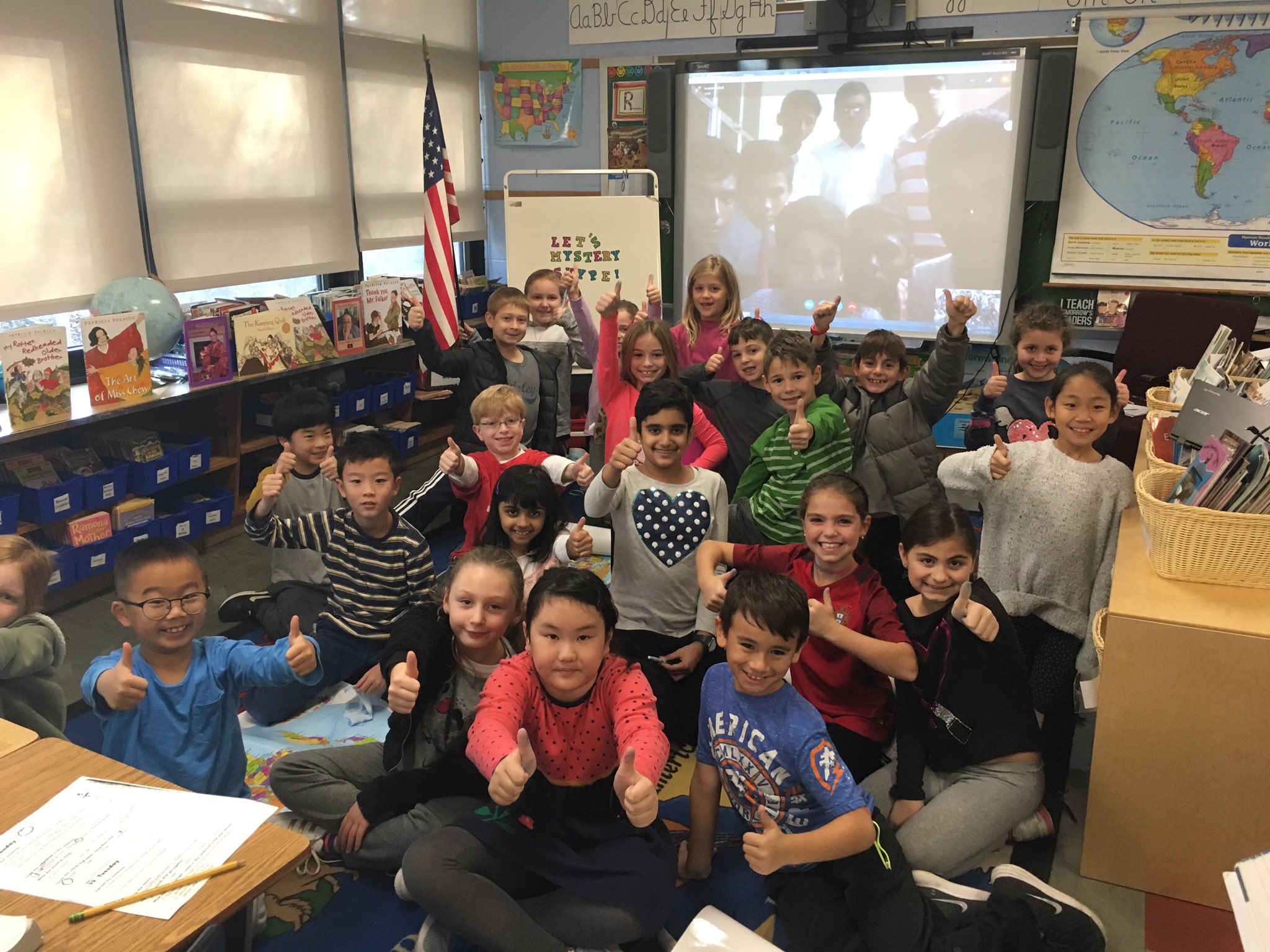

Many teachers start out arranging a “Mystery Skype” with a class in another country, where the kids ask each other questions to figure out where the students on the other side of the screen live. Teachers also connect their classes with experts to augment the curriculum they’re teaching, such as video calls with the curator of an Egyptian museum, an Olympian athlete or a Yellowstone National Park ranger.

The connection can seem so real that Phuti Ragophala’s students in South Africa were afraid to touch the screen when an oceanographer in California showed them a sea turtle. Ragophala says her students, despite living in an area with gravel roads and no Wi-Fi, are “globetrotters” who have been inspired by their Skype calls with celebrities and other prominent people around the world.

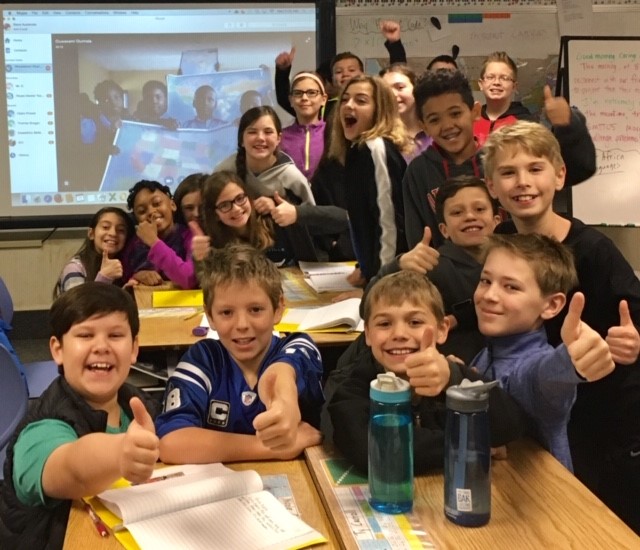

Time zones can limit the regions available for live Skype sessions during normal school hours – though they can also add an element of fun. “I always like to end the day with a Skype call with Australia so the kids can call into the future, since 3 p.m. our time will be 7 a.m. the next day Melbourne time,” says Steven Auslander, a fifth-grade teacher in the U.S. state of Indiana.

The focused nature of the two-day Skype-a-Thon offers an annual opportunity to bypass those time-zone challenges. Karey Killian says she doesn’t host slumber parties during the event for her students, in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. But since others – such as Kumar – do, her students get to meet kids in India every year who are 9.5 hours ahead but stay up all night for the Skype-a-Thon to participate in round-the-clock sessions with classes on the other side of the globe.

Killian, a librarian, makes sure each of the 50 elementary classes she teaches gets at least one Skype opportunity during the school year.

“I usually try to get to Antarctica,” she says. “There’s a scientist who’s down there, and you actually get to see the penguins sitting on their nests. One time we did a call and there was a volcano erupting in the background. I didn’t even know there were volcanoes in Antarctica.”

Killian’s classes are used to the chilly winters of the U.S. Northeast, but Kumar said his students, who live in a flat, hot region of southern India, get an even bigger surprise when they experience a Skype call with an Arctic research team. “It’s eye-opening for them to discover that such a cold region exists in the world,” he says.

The Skype sessions open students’ eyes in other ways, too.

Killian says most of her students in rural Pennsylvania had never met a Muslim until she arranged a Skype session for a class of second graders with a teacher in Indonesia. “The kids were amazed to realize that not everyone celebrates Christmas or waits for Santa to come,” Killian says. “But she told them about other Muslim holidays where they get together to celebrate with friends and family.”

Meeting other students in far-flung places has prompted many to organize book drives or map donations for classes that are struggling to afford supplies, as well as helped them gain confidence from each other in their abilities to speak a foreign language, ask questions or even learn how to spell and say new words. Some teachers say one 30-minute Skype call with an expert where kids get to actually see the things they’re learning about can teach what an entire week with a textbook does.

“Skype provides a gateway for students to learn about other people, within the curriculum teachers are teaching,” says Anthony Salcito, vice president of worldwide education for Microsoft. “And it’s not a one-way street – kids in developing countries use their talents to help kids elsewhere. It’s just the beginning of opening up peace across the planet and enabling kids to see their world differently.”

Mio Horio, a teacher in Japan, says she uses Skype sessions to dive deeper into her lessons, breaking down stereotypes and helping her students understand the complexities of the world.

When one of her classes was studying how palm oil plantations were supplanting forests in Malaysia, harming orangutans, she had them do a video call with a group of Malaysian teens to better grasp the complications of outright banning the practice.

The kids were amazed to realize that not everyone celebrates Christmas or waits for Santa to come. But she told them about other Muslim holidays where they get together to celebrate with friends and family.

Horio and her students, in turn, have shared their knowledge of what to do during natural disasters, as they did in a Skype session on earthquake safety with Tran Thi Thuy’s class in rural Vietnam.

Tran, a teacher who says she was raised in the poorest family in her village, bought her own Wi-Fi router to bring the world to her students through Skype. She says the sessions, which are in English, take her kids beyond the grammar and vocabulary that are traditionally taught, to actually speak the language themselves, even though they’re in an area where native speakers are rare. Talking with people in other regions helps students learn to understand different accents as well, Horio adds.

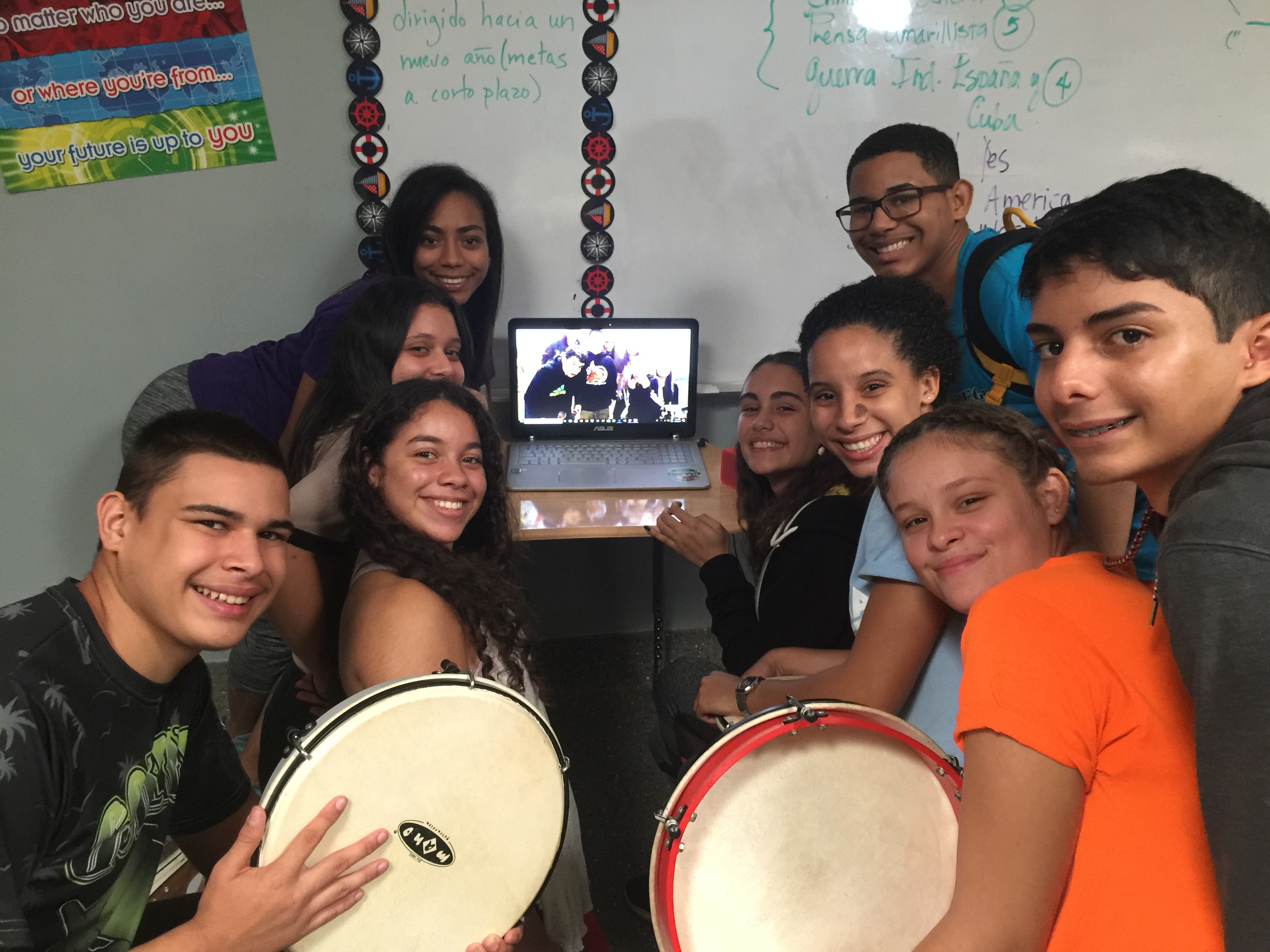

Darlene Colon, who teaches technology and English as a second language to middle schoolers at a public school for athletes in Puerto Rico, has started a monthly rotation of Spanish and English sessions with classes in Texas and Kentucky. The kids are helping each other with pronunciation, she said — a welcome diversion for her students, who are still struggling from the impact of Hurricane Maria last year.

Colon’s school building was destroyed in the hurricane, about two months before last year’s Skype-a-Thon. A hallway in a neighboring school became her classroom, and even though the area still didn’t have electricity, she found a way to charge her computer and boosted the data service on her phone so she could connect her class for the event.

“The kids didn’t have anything, no electricity or water. Some had lost their homes, family members and friends, and they were very stressed,” she says. “So this helped them forget their troubles and just enjoy themselves.”

When the electricity came back on in time for Christmas, her students’ joy was so infectious that a spontaneous music jam and dance broke out during a Skype session with a class in New York.

“Everyone was so happy, and even though all the news was about the chaos here, we were able to show that wasn’t necessarily the whole story,” she says. “Even though it was difficult for us, we were willing to continue and participate.”

Above all, teachers say the Skype sessions highlight how much the kids have in common with each other – such as Horio’s Japanese students discovering they had the same favorite Dragon Ball comic book character as a class in Spain.

“We’ve had sessions with 78 different countries,” says Kumar, the STEM teacher in India. “But in spite of all that diversity, the sense of commonality is what comes through to the kids. When they laugh and share things, that’s what they identify: oneness within diversity.”