For the love of Aaron, and all children who may be susceptible to SIDS

It was the photo that caught his eye. Juan Lavista Ferres had just become a first-time father, and he was jubilant. He brought a picture of his newborn child to work, and he saw a similar photo of an infant on his boss’ desk. Smiling, Lavista approached his boss, John Kahan, to ask him about his child.

The baby’s name was Aaron, Kahan said. He had beautiful reddish hair like his mother, Heather, and his three older sisters. He was the Kahans’ only son. And he died of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) a few days after he was born.

SIDS is among the most terrifying and mysterious causes of deaths in infants. There is no known reason for why a baby stops breathing and dies. Approximately 4,000 infants in the U.S. die each year from sudden unexpected infant death (SUID), which includes SIDS. There has not been a drop in such deaths since the mid-1990s.

“When a child dies, probably the worst thing the doctors can tell you is that they don’t know why,” says Kahan. The question churns over and over in a parent’s mind.

Kahan, Microsoft general manager of Customer Data and Analytics, has helped raise more than $200,000 over the past two years for SIDS research at Seattle Children’s Research Institute. It was at Seattle Children’s Hospital where doctors tried to save Aaron’s life when he stopped breathing.

New father Lavista, stunned and deeply saddened by Aaron’s death, wanted to volunteer to do something. “John was the first person I met who had a child who died from SIDS,” Lavista says. “I started learning about SIDS, and it was not very clear how to prevent it; there wasn’t a lot of information.”

How to begin to unravel the mystery? As senior director of Data Science, Data and Analytics for Microsoft, Lavista thought: “What if we not only give our time, but our skills and help from a data science point of view?”

The result of that effort: On Wednesday, data scientists at Microsoft donated a powerful new SIDS research tool to Seattle Children’s Research Institute, one of the top five pediatric research centers in the nation, and are planning to offer free access to the tool to researchers around the world. Microsoft Philanthropies donated Azure cloud services to power the tool and, as a result, aid medical research.

“We believe cloud services can help unlock the secrets held by SIDS data and provide new insights for the scientists working to identify the causes of, and put an end to, SIDS,” says Mary Snapp, corporate vice president and head of Microsoft Philanthropies.

When Lavista asked if coworkers were interested in working on the SIDS project on a volunteer basis, the response was immediate and heartfelt. More than a dozen data scientists donated more than 450 hours over nights and weekends the past year, including several who are parents or are getting ready to have families of their own. Microsoft’s Giving campaign matches volunteer hours at $25 per hour, which goes to the nonprofit for which employees volunteered. That means the team raised over $11,250 for Seattle Children’s Research Institute by working on this project.

“Everyone was very motivated to help,” says Urszula Chajewska, principal data and applied scientist, who coordinated the project. “We realized very quickly the large impact we could have, because there are not a lot of researchers in the world working on SIDS. But more importantly, SIDS was never analyzed based on a dataset of a similar scale.”

And until now, not much data about SIDS has been available on such a large scale. Studies that have been done involved dozens, or perhaps hundreds, of cases.

The Microsoft team used publicly available, raw data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). That data includes information on 29 million births, and over 27,000 sudden and unexpected infant deaths from 2004 to 2010.

The CDC raw data was just that: It hadn’t been analyzed, processed or extracted in any way. It was a gold mine of information without any shovels to get there. The Microsoft team developed a tool that uses statistical analysis and machine learning to interpret the CDC data on SIDS in a way that was never done before.

The research tool runs on Microsoft Azure, a powerful cloud computing platform, that crunches the CDC numbers and churns out potential connections, or “correlations,” between hundreds of data points and SIDS.

Now researchers can use the tool to find new correlations. “Upon further investigation, some of these correlations may turn out to be causal and lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms behind SIDS,” says Chajewska. The team hopes that ultimately leads to finding the causes of SIDS, and the development of preventive measures.

To make it easier for researchers to understand the data, the correlations are displayed visually in Power BI. Researchers can select from thousands of combinations of factors they think might be important to SIDS – such as a child’s birth order or the parents’ ages – to see potentially new correlations.

Nino Ramirez, Ph.D. director of the Center for Integrative Brain Research at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, has spent years studying SIDS and neurological disorders like autism, epilepsy and ADHD.

“SIDS is a very complex disorder,” he says. “For many years, there was the hope that you could find the gene, or the cause for SIDS. But the reality is, there are many factors that come together to create a perfect storm that results in a child dying. That’s where Microsoft’s work will play a big role. They have given us a means to look at different factors at the same time.”

What Microsoft has created with the research tool, Ramirez says, “brings together data science and the medical sciences. I think this marriage, this new combination, will be very important, not only for SIDS, but for health research in general.”

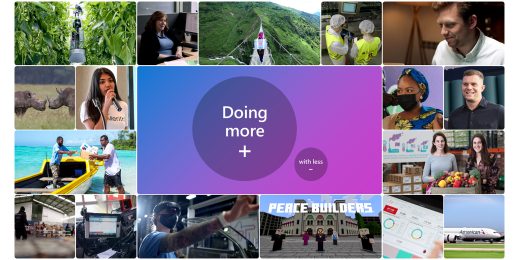

Sushama Murthy, Shirley Ren. John Kahan is in the foreground of the photo. (Photo by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures)

When the data scientists first presented their work to Kahan, he was so moved he had to leave the room for a few moments. “I couldn’t believe what these people had done,” he says.

Three years after Aaron’s death, the Kahans had another child, a daughter, Sadie, who is now 10. His oldest daughter, Emily, 23, had her first child, a son, 16 months ago.

“I feel incredibly blessed,” Kahan says. “I have four healthy children, and an amazing grandson. I work with a staff that is deep and caring, and they’re diverse in skills and capabilities. And I work for a company that encourages us to use our skills to solve world problems.”

Kahan has raised money for SIDS research in a variety of ways, including by hiking – last summer, in Aaron’s name, he reached the top of Mt. Kilimanjaro in Africa, an accomplishment for any person, but especially for Kahan. “You have to understand, I grew up in New York City, so my idea of hiking and roughing it was staying at the Marriott Courtyard,” he says dryly.

He also wrote a book, “The Arctic: A Photographic Journey,” featuring his photography from that area of the world, with net proceeds going to the Seattle Children’s Research Institute.

Kahan continues to run hiking-based fundraisers to support SIDS research, and many members of his team, beyond those who developed this research tool, join him. They’ve spent hundreds of hours on such fundraisers and generated many thousands of dollars.

It has been a long journey in more ways than one for Kahan.

“I feel better mentally and physically than I’ve felt in my entire life,” he says. “It’s because I’m on a personal mission for something that I actually think that we can solve. I really believe because of all the work we’re doing that this will be solved. It may take a year, two years, five years – but we will chip away at this thing, one piece at a time.

“I want to ensure that no parent experiences the pain of losing a child from SIDS, or worries that their child could be next.”

Contributions to SIDS research at Seattle Children’s may be made to the SIDS Research Fellow Fund. The Kahans are matching gifts made to this cause, up to $50,000. The Jack R. MacDonald Research Endowment at Seattle Children’s will also match up to $50,000.

Top image: John Kahan in his office at Microsoft, with a photo of his son, Aaron, on the computer screen. (Photo by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures)