Microsoft Hackathon 2015 winner extends OneNote to improve learning outcomes for students

Education is a must-have ingredient for success. And to succeed in education, reading and writing is essential. The challenges that come with language barriers and learning disabilities such as dyslexia are vast and varied, but luckily technology is able to help many students overcome literacy obstacles.

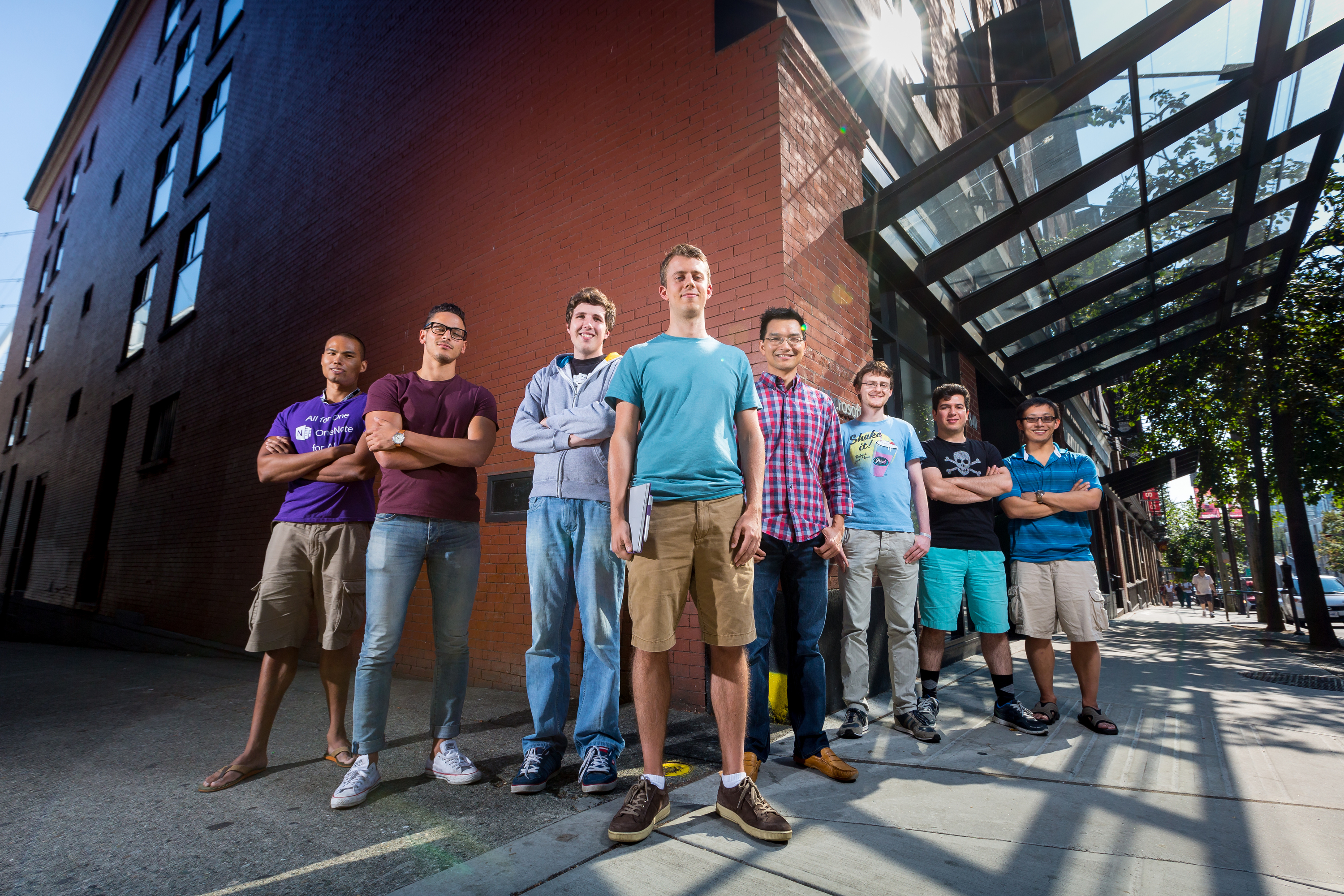

One solution is coming from a team at Microsoft that spans collaboration between Windows, OneNote, Bing and Microsoft Research: the OneNote for Learning extension. The team and their project emerged victorious over more than 3,300 other projects and 13,000 other hackers around the world competing in the company’s second annual //oneweek Hackathon during the last week of July.

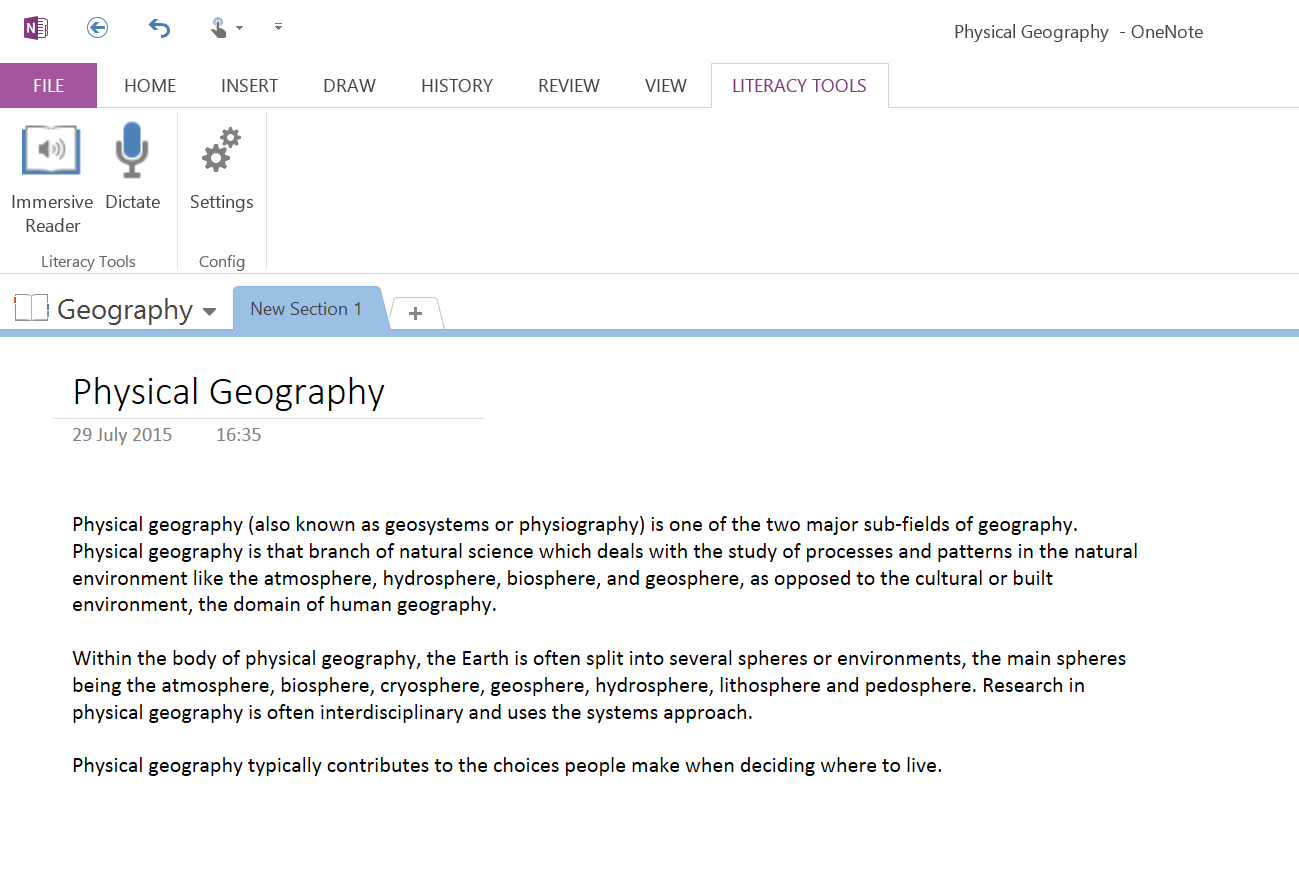

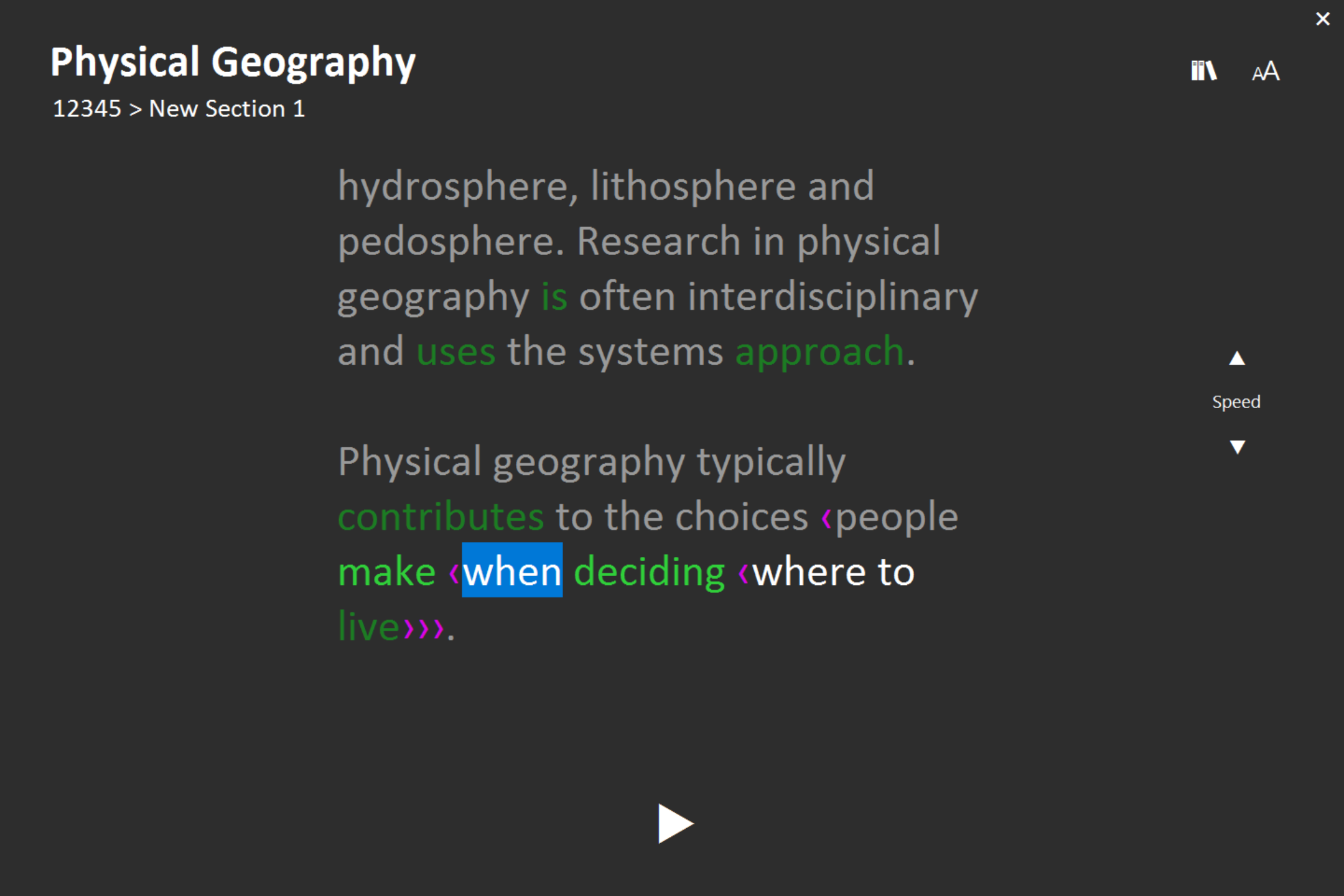

Sebastian Greaves, a Vancouver-based OneNote developer, thinks of the extension as a toolbox with many small tools that can solve big problems. It has special text formatting tools that can make reading, writing and note-taking easier. Features include enhanced dictation powered by Bing speech recognition services, immersive reading that uses Windows services of simultaneous audio text playback with highlighting, and natural language processing that relies on Microsoft Research.

“One of the key things we wanted to achieve is to make sure no student ever got behind in their education because of difficulties with reading,” says Greaves, who drove down to Redmond, Washington, with others from his office to work side-by-side with the entire team during Hackathon. “We wanted to make sure that was as little a barrier as possible, so they can focus on what they’re learning.”

More than a dozen of Greaves’ teammates worked together for more than eight weeks to create the free OneNote extension, which will debut this fall in several schools in the U.S. and France.

“One of the great things about this project was that we utilized loads of different services,” Greaves says. “It meant that we could do so much more than we could’ve done if we had to write it all from scratch.”

By connecting with so many existing technologies across Microsoft, the team was able to do a lot in a short period of time. Every team member made key contributions to push the project forward, says Jeff Petty, the accessibility lead for Windows for Education and the program manager who led the grand prize-winning team.

“It takes a tremendous amount of work to envision it, pull it together and then deliver it in such a way where it just makes sense for people,” says Petty. “I don’t think we could have done something as powerful without having real breadth and depth on the team.”

Petty was interested in finding opportunities to deliver better learning outcomes for students and teachers. He focused on dyslexia, which affects as much as 20 percent of the population. He connected with a team in OneNote that was working on solving problems for dyslexic readers, such as visual crowding. That team found ways to put more space between letters, which makes words more readable.

That team had won an internal OneNote hackathon in the spring for that idea, led by Valentin Dobre, a software engineer, and Greaves.

Petty recognized this was a great start, but soon he and the expanding team also realized they could do more to pull together a more wide-reaching solution for students.

“When you address challenges with reading and writing, the benefits extend far beyond the original audience you had in mind,” says Petty. “By solving a problem for one audience, we’re actually going to make life easier for many more people.”

In his work with Windows, they were able to take advantage of the immersive reading function, with the ability to highlight text and have it read aloud, which increases reading comprehension. The next big connection was finding font and reading experts in Windows research.

“They helped us gel,” Petty says. “They backed up our solutions with science. Nothing that we built came from what we just thought was a good idea. It’s all based on prior research. These are proven interventions for students with dyslexia and also techniques that create a better reader for everybody.”

The researchers provided additional ideas for improving the team’s tool chest, like breaking words down into syllables to improve word recognition, and reading comprehension mode, which highlights different parts of speech like verbs and subordinate clauses.

Mira Shah was the team’s user research expert and formerly a speech pathologist. She gave them a real-world perspective with her experience in schools and seeing firsthand what worked and what didn’t.

Petty served as the glue to the team, bringing a broad perspective to reading and writing, and kept them on track with guiding principles, such as developing something backed by science, and keeping everyone focused on delivering something that would make a difference in people’s lives – something they could all be proud of, regardless of the outcome.

“I think we can make reading and writing better for everybody,” Petty says. “And if we really focus on people with disabilities, and we understand what works for them, we can bring those designs and solutions to our products that benefit everyone.”

Once the team came together, they shared a common drive to finish what they started.

“At no point did we think we were not going to ship,” Petty says. “OneNote was not interested in doing this as an experiment. Hackathon forced us to create a prototype they could polish to take it to schools in the fall.”

During the three very intense days of the //oneweek Hackathon, everyone on the team met each other for the first time, working practically nonstop under the Redmond tents that housed 3,000 people during the working sessions. Having the Vancouver-based OneNote development members – Greaves, Dominik Messinger and Pelle Nielsen – join the rest of the team was critical to their success.

“We could not have done it without them being there,” Petty says. “It was a completely different way of working, to get rapid feedback and iterate and iterate and iterate. We’d give them protected blocks of time where they got no additional feedback. Then we’d come back together for joint review. We were doing iterations while they were coding, then we had to decide to either refine functionality or bring new features. There is no way we could have made the same progress had we not all been there.”

At the Hackathon, the team also met the mother of a daughter who has severe dyslexia, working with another team. She believed what the OneNote for Learning team was doing was going to make a difference, and her reaction gave them even more confidence they were on the right track.

And for developer and team member Dominik Messinger, whose native language isn’t English, the project provided him with better tools to improve his own language skills, such as dividing words into semantic units for better comprehension – and pronunciation.

“I caught myself reading out some notes for OneNote documentation, and just listening to it, discovered some words I’ve totally pronounced wrong. Text to speech is pretty useful,” Messinger jokes. “Also, having short term goals and having all this energy, coding really fast and collaborating really, really fast – that was quite an experience. We can be proud of what we achieved in so few days.”

For the whole team, the Hackathon exemplified the best things about being able to tap into the entire company for resources.

“I think there’s a lot of strength in working across orgs and teams, and getting to work with people we might otherwise not get to work with, such as the accessibility team,” Nielsen says. “Learning how important it is to choose the right color scheme or font was eye opening.”

While everyone brought their own strengths to the project, its ultimate purpose served as a north star that maintained the team’s focus.

“We wanted to make sure this was a non-stigmatizing feature. This is something anybody could use. Someone using the extension wouldn’t raise a big red flag that they’ve got a disability,” Nielsen says. “For me, the most important thing was recognizing the value of our goal. It doesn’t matter how cool the tech is if it doesn’t help anyone. That’s what is so compelling about this project. We’re making learning easier for every single student.”

Lead image: More than a dozen team members worked together for more than eight weeks to create the free OneNote extension, which will debut this fall in several schools in the U.S. and France.