John Robinson was born without the extensions of his arms or legs. As a child, and an adult, he rejected wearing prostheses. They worked, but they were uncomfortable, and he never felt like himself with them on. And that’s all Robinson really wanted to be, just himself.

It’s why he understands the frustrations many other people with disabilities face in trying to get people to see who they really are – especially when it comes to looking for employment. And why his organization, Our Ability, is among seven new recipients of Microsoft’s AI for Accessibility grants to people using AI-powered technology to make the world a more inclusive place.

In 2018, when the $25 million program was announced, nine organizations were given grants to work on a variety of projects, some from scratch, some already underway.

The new grantees, announced in conjunction with Global Accessibility Awareness Day May 16, are: University of California, Berkeley; Massachusetts Eye and Ear, a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School; Voiceitt in Israel; Birmingham City University in the United Kingdom; University of Sydney in Australia; Pison Technology of Boston; and Our Ability, of Glenmont, New York.

Their projects may differ, but the people behind them share a passion for how technology can improve the lives of their fellow human beings.

“What stands out the most about this round of grantees is how so many of them are taking standard AI capabilities, like a chatbot or data collection, and truly revolutionizing the value of technology in typical scenarios for a person with a disability like finding a job, being able to use a computer mouse or anticipating a seizure,” says Mary Bellard, Microsoft senior accessibility architect.

John Robinson takes a break during a recent job fair hosted by CDPHP and Living Resources in Albany, New York. CDPHP is a community-based, not-for-profit health plan in New York state, and nonprofit Living Resources provides growth opportunities for people with disabilities. (Photo by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures)

The one-year grants provide use of the Azure AI platform through Azure compute credits and can also include Azure compute credits plus engineering-related costs. AI for Accessibility has three focus areas: communication and connection; employment; and daily life.

Robinson of Our Ability knows about all of those. But it was his employment journey after college that always remained with him. He went through a discouraging, 4-1/2-year search to find a job – the right job. During those years, he sent out hundreds of resumes, and had 20 to 25 interviews for work in ad sales at TV stations. He also married and started a family.

“If I were really going to give up, I would have given up after the first 10 or 20 interviews,” he says. “That’s not who I am.”

He vowed, someday, to find a way to improve the process for others who have disabilities. “You want to be seen as the person you are, in total, not just the shell that you are on the outside,” he says.

After working at TV stations for many years, Robinson founded Our Ability in 2011 to bring businesses with employment opportunities together with people with disabilities looking for jobs.

Now, with the AI for Accessibility grant, and working with students from Syracuse University, Our Ability wants to create an accessible and intuitive AI-powered chatbot to help businesses find workers, and to help people with disabilities find employment that’s meaningful to them.

“So many of them are taking standard AI capabilities, like a chatbot or data collection, and truly revolutionizing the value of technology in typical scenarios for a person with a disability.”

And with good reason: The unemployment rate among people with disabilities is about twice as high – 7.9 percent – as for those without disabilities, according to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Disability Employment Policy (ODEP). Robinson says the rate is actually closer to 65 percent when you factor in another significant number: Only one out of every five people with disabilities is in the labor force, according to ODEP.

Of course, human job coaches are helpful, Robinson says, but even some of them still tend to look at the disability first, and not the person.

“The internet is a more level playing field” that way, he says. “The individual with a disability will talk to the chatbot about who they really are, and maybe more importantly, who they want to be.”

Our Ability has 20,000 unique users that visit its website every year, but not all of them go through the manual process of filling out the forms on the site; the chatbot will help with that, Robinson says. It will also help individuals “find the skills they need for the jobs that they want.”

The Our Ability website now includes an area where individuals can build their profile, companies can search the database, and individuals can search job openings, and “they can find each other organically that way, or they can reach out to us and we can make an email introduction as best we can for opportunities that we know about,” he says. That’s not ideal, though.

The chatbot, he says, “will provide a much more rapid way of getting more people to connect with one another. By creating a place where we assess real-life skills, train real-life skills and match them with employment – that’s every disability job coach’s goal in the last 50 years,” he says.

“We’re going to be able to do it with technology a lot faster and a lot better.”

Dexter Ang says it was his mother who inspired him to help develop a nerve-sensing wearable device that can be used to control digital devices. (Photo courtesy of Dexter Ang)

Every day, Dexter Ang was growing more frustrated as he watched his mother deal with the indignities of ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. She was diagnosed with it in 2014.

The progressive disease attacks nerve cells that control muscles throughout the body. Over time – for many, anywhere from a year to decades – it robs people of their ability to walk, to use their arms and hands, to talk and ultimately, to breathe independently.

Ang had been working in Chicago in the financial world of high-frequency trading before his mother was diagnosed. He decided to move to Boston to help take care of her. Over the course of a year, there were fewer activities she could do with her hands. Eventually, she couldn’t use utensils to eat. She couldn’t dress herself. And she couldn’t maneuver the mouse to use her laptop, which she relied on for reading e-books from the library.

“I asked her when the last time was that she had read a book, and she said six weeks — because she couldn’t click a mouse,” Ang says. “That just made me tremendously sad, because that was one of the only things that she could still enjoy, and that was just gone.”

Ang, a graduate of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) with a degree in mechanical engineering, spent months meeting with experts and poring over information about existing technologies to see if there were any that could help his mother.

“Ultimately, a lot of it was not useful — it was complicated and not well-designed,” he says. He credits his mother for inspiring him with a question she asked: What if a person could use their nerve signals to help control a mouse?

Ang wanted to learn more, returned to MIT as a graduate student and co-founded Pison Technology. The company, one of the AI for Accessibility grantees, is developing a nerve-sensing wearable, similar in appearance to a watch, to control digital devices using small, micro-movements of the hands and arms.

“Our proprietary technology can sense nerve signals on the surface of the skin,” Ang says. “Our machine-learning algorithms can classify those voltage signals into discernable actions,” such as simulating a mouse click to help interact with a computer.

In 2016, the ALS Association awarded an ALS Assistive Technology prize to Ang and Pison co-founder David Cipoletta.

“People are looking for products or services to make things easier, and AI might be able to help.”

“They blew the judges away with their easy-to-use, self-contained communication system,” the ALS Association said on its blog. “People living with ALS are able to learn and use the system to communicate in minutes. We observed first hand as participants (and) were thrilled with its comfort and usability while testing out their technology.”

The device, which is now undergoing testing, can help improve communication for people with other neuromuscular disabilities, including multiple sclerosis, Ang says. He wants it to be made widely available, around the world, at a low cost, and easy to purchase online. He believes his mother, who died in 2015, would be proud of the work he and his team have done.

When a person’s “physical world shrinks” because of a disease like ALS, for many “the digital world is the only world that is still out there for people to express themselves, and to connect with others,” Ang says. “To be able to maintain and increase access to that digital world is exceptionally important for people with disabilities.”

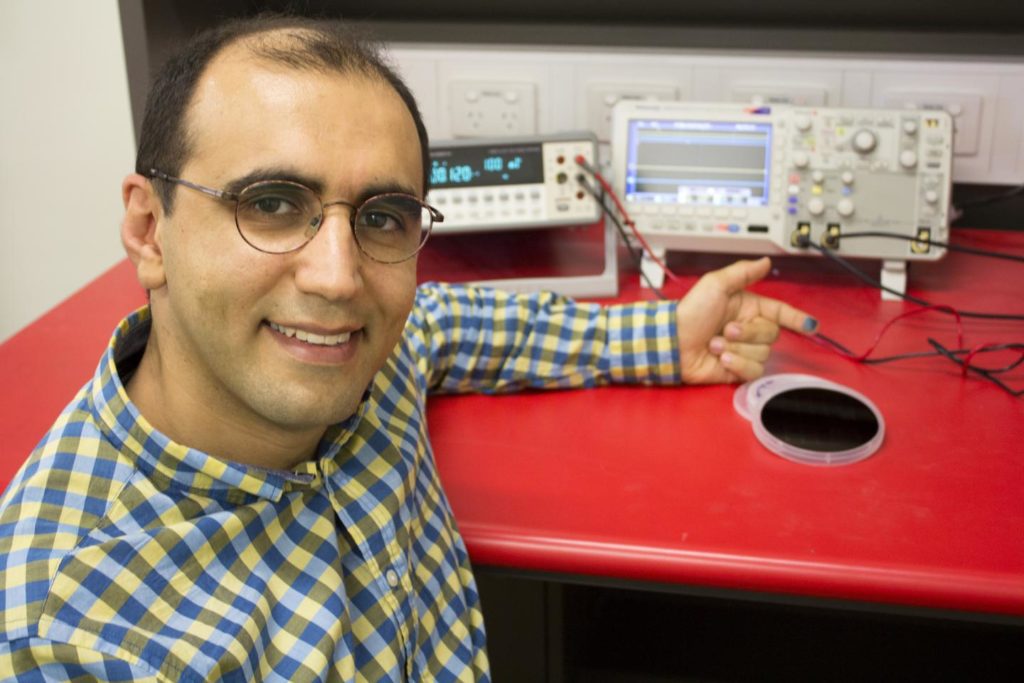

Omid Kavehei and his colleagues at the University of Sydney have been working to develop a non-surgical device that would provide advance warning of a seizure for people living with epilepsy. (Photo courtesy of University of Sydney)

For people with epilepsy, one of the biggest dangers is having a seizure while driving. In some places, patients need to prove they’ve been seizure-free for a year in order to be allowed behind the wheel, which can create psychological and economic stress of its own.

It’s a problem that got Omid Kavehei thinking: What if there was a way to warn drivers who have epilepsy that a seizure could be coming, so that they have time to safely pull off the road?

Kavehei, a senior lecturer at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies, and his colleagues at the University of Sydney – also a new AI for Accessibility grantee – are working on a potential way to help. They have been using deep learning to develop an analytical tool that can read a person’s electroencephalogram (EEG) data via a wearable cap, then communicate that data back and forth to the cloud to provide seizure monitoring and alerts.

It’s a very new approach to a very old disorder. Awareness and writings about epilepsy date back to ancient times, but so do myths and social stigma about it that continue to persist.

“Some people think epilepsy is contagious — it’s not — and we hear stories of misbelief and misguidance on social media almost every day,” says Kavehei. “I’ve read it in tweets — ‘My child can’t be enrolled in such-and-such primary school because there’s a student there with epilepsy.’ We are living in 2019, but still, you can’t believe some of the stories you hear.”

More than 50 million people worldwide live with epilepsy, making it one of the most common neurological disorders globally, according to the World Health Organization.

“Some people think epilepsy is contagious — it’s not — and we hear stories of misbelief and misguidance on social media.”

“To have a non-surgical device available for those living with epilepsy will make a significant difference to many, including family members, friends, and of course those impacted by epilepsy,” says Carol Ireland, CEO of Epilepsy Action Australia, which is among the groups working with the university on the project.

“Such a device would take away the fear element of when and if a seizure may occur, ensuring that the person living with epilepsy can get into a safe place quickly.”

Kavehei and his colleagues want to first test a wearable cap on epilepsy patients using driving simulations. They will leverage Azure Machine Learning to attempt to predict seizures from human signals.

The research being done by all of the AI for Accessibility grantees “is an important step in scaling accessible technology across the globe,” says Bellard of Microsoft. “People are looking for products or services to make things easier and AI might be able to help.”

Lead image: Leanne Strong talks with John Robinson at a recent job fair hosted by CDPHP and Living Resources in Albany, New York. (Photo by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures)