People living with ALS share their data in extraordinary effort to end the devastating disease

Maybe, Joel Shamaskin thought, he was working too many hours, not getting enough sleep. That wouldn’t have been unusual for the longtime primary care doctor at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

The change was subtle, happening over the course of a few months. Sometimes, as he rounded the patient’s exam table, his legs didn’t advance quite as quickly or smoothly as they normally did. He might catch the rubber sole of his shoe on the tile floor. It wasn’t like him.

Neurology tests in the spring of 2016 revealed that he had ALS. He was in shock about the diagnosis — but also determined that something good come from it. He’s now one of nearly 1,000 people living with ALS from around the United States participating in a massive project that may offer more hope than ever before of finding a cure.

“The main way I felt I was going to cope was to be as proactive as I could in looking for potential new treatments and research trials,” he says. “Knowing that this is going to help others is as much of a motivator as anything.”

Called Answer ALS, its mission is to build the most comprehensive collection of clinical, genetic, behavioral, molecular and biochemical data on people living with ALS. With the help of artificial intelligence and machine learning, researchers will be able to analyze the data to uncover new insights about the causes of ALS and develop possible therapeutic treatments.

Microsoft is investing $1 million in cloud-computing resources for the nonprofit, which will make the huge repository of valuable data openly available to researchers around the globe.

All of that data is critical, as now there is no cure. ALS, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, is a progressive disease that attacks nerve cells that control muscles throughout the body. Over time – for many, anywhere from a few years to 10 years – the fatal disease robs people of their ability to walk, to use their arms and hands, to talk and ultimately, to breathe independently.

In the United States, more than 5,600 people are diagnosed with ALS every year. In 90 to 95 percent of cases, there is no family history of the disease; it appears to occur randomly, with no clearly associated risk factors.

Answer ALS’ research effort is “the single largest and most comprehensive ALS research study in history,” says Clare Durrett, Answer ALS Foundation co-director and managing coordinator. “With a goal of 1,000 patient participants, the amount of data collected per participant is over 6 billion data points per person.”

Microsoft is working closely with scientists and researchers from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to make the data available to researchers when it is ready in a few years. All of the data is stored on the Microsoft Azure cloud, which will enable secure sharing and privacy of the sensitive health data.

Durrett says Microsoft’s role has been key.

“To effectively utilize such a large knowledge base, we needed a partner who could commit to the effort and have the expertise to ensure the integrity of the data,” she says. “We are building a knowledge base so strong that the global ALS research community will be able to harness the power of artificial intelligence to ultimately predict a patient’s disease course and optimal therapy.”

Only if we work together and embrace the power of new technologies can we come closer to finding a cure.

The inspiration for Answer ALS came from the ALS Summit in 2013, a gathering for researchers, people living with ALS, physicians and caregivers hosted by former pro football player Steve Gleason and his nonprofit organization, Team Gleason.

Gleason was diagnosed with ALS in 2011, and part of his quest has been to help in finding a cure for it and to improve day-to-day life for people with ALS. Gleason’s work with Microsoft employees during the company’s first Hackathon in 2014 provided him with a way to use his eyes to maneuver his wheelchair. That led to Microsoft’s development and release last year of Eye Control for Windows 10, eye-tracking technology that allows people with disabilities to type with their eyes.

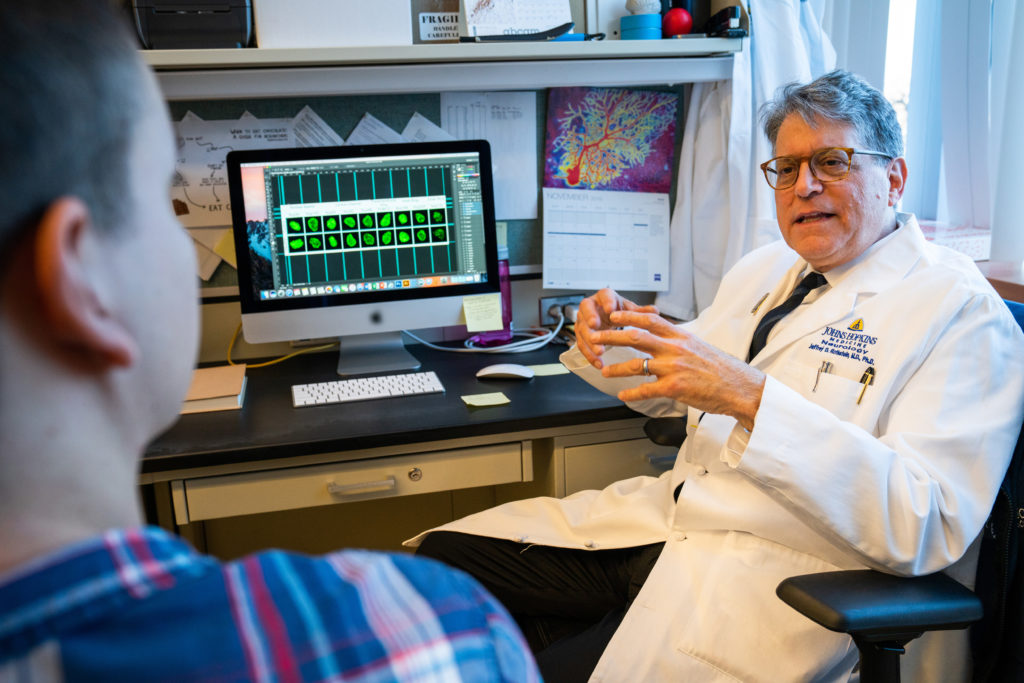

For Dr. Jeffrey D. Rothstein, who is the founder and director of the Answer ALS program, the project represents the opportunity of a lifetime for the disease that has been the focus of his work since he was a resident at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where he is now a professor of neurology and neuroscience. He is also founding director of the school’s Robert Packard Center for ALS Research, which runs the Answer ALS program, and which also coordinates dozens of researchers worldwide to focus on ALS, along with caring for more than 400 people with ALS every year.

“This is a disease that has had not such a great track record in finding therapies,” Rothstein says. “ALS takes someone in the prime of life, and they slowly — or rapidly — lose all their ability to move.”

When he describes to his medical students what it’s like to live with ALS he uses this analogy: “Imagine you’re on an international flight. It’s eight hours. You’re in the middle seat between two people. You can’t move at all. You can’t get up to go to the bathroom. You have no ability, other than to maybe move your mouth and eyes. And that’s kind of what happens — patients become locked in. And that’s just devastating to someone. They can’t hold their babies. They can’t touch anything. They feel things, but they can’t move. It’s a truly cruel and devastating disease.”

The “heart” of Answer ALS is ultimately to personalize drug treatment approaches to ALS by defining biological subtypes of people with ALS, similar to how breast cancer is now treated, Rothstein says.

“We no longer do a biopsy and look under the microscope and say, ‘Ah, yes, it’s breast cancer,’” he says. “We analyze and say, ‘Well it’s a certain kind of breast cancer, and breast cancer responds to certain drugs.’ And in so doing, we personalize medicine, in which we target the therapy to the right group of patients. For ALS, that’s is exactly what we hope Answer ALS will allow us to do.”

I want to do my part to let the researchers advance their work.

Among the people from Microsoft working on the project is University Relations Director Elizabeth Bruce, who says “one of the amazing things about Answer ALS is that they plan to make all of this data accessible to an entire community of researchers worldwide, across disciplines, opening up the possibility of discovering a cure.”

One of the ways to make biomedical data more accessible is Galaxy, an open, web-based platform initially developed for genomics research, and an important tool for researchers who don’t necessarily have a background in computer science. To enable the Answer ALS researchers to use Galaxy for its compute research, Microsoft built support for Azure into CloudBridge, the code Galaxy uses to manage resources in the cloud.

“This work is an important step in making Azure more accessible to scientists and researchers around the world,” Bruce says.

“There are many different initiatives working on an answer” to ALS, she says. “Only if we work together and embrace the power of new technologies can we come closer to finding a cure.”

People with ALS are seen for blood draws and data collection every three months at Answer ALS clinics around the country, including sites at Johns Hopkins, Northwestern Medicine in Chicago and Ohio State University in Columbus.

Connie Rosete, an Answer ALS participant, says she went through several misdiagnoses — a frustrating but not uncommon experience with ALS — before learning a year ago she had the disease.

Rosete was an elementary school psychologist in Los Angeles County. It was one of her coworkers who noticed she was walking more slowly than usual and asked if she was in pain.

No, Rosete said, she wasn’t in pain — something that’s not generally evident in the early stages of ALS. Rosete didn’t think too much more about it. But then her husband also noticed a change in her gait. That started an odyssey of medical appointments and tests, with a diagnosis of ALS last fall.

Rosete and her husband, married more than 40 years, had just retired from their jobs, something they’d planned for many years to do at the same time. They had big dreams. They love to travel.

“We were going to live in Guatemala for six months, and Costa Rica for six months,” says Rosete, 64. “We were going to go to Europe and live there for a few months. It’s like all our plans were deviated.”

But Rosete says she doesn’t have time to dwell on what cannot be, only on that which can, and she still sees travel in the picture. She and her husband have been taking “short little trips” to see how Rosete does with the wheelchair that she is using now. She’s hoping Italy is on the agenda for next spring.

“Like I told my husband, let’s enjoy what we have today,” she says. “Take advantage of what you have, whatever condition you’re in, and do what you can do.”

For her, that includes participating in Answer ALS.

“I want to do whatever I can do to help the cause,” she says. “I enjoy life today as I am, instead of wasting life, saying I wish I could. So that’s important to me.”

Jay Quinlan feels the same way. Growing up in New Orleans, Quinlan, 51, loved hearing his uncle’s stories about being a prosecutor. He knew from an early age it was what he would do. And he stuck to his plan, earning his law degree from Louisiana State University, going on to become an assistant district attorney, a state prosecutor and ultimately, a federal prosecutor.

The courtroom was Quinlan’s second home, in many ways, a place where he was at ease. Three years ago, he started noticing he was having some difficulty gripping file folders at work. Then, at home, he’d be trimming his fingernails and he would be unable to hang onto the clippers, dropping them to the floor.

“I certainly didn’t think it was anything like ALS,” he says. “I didn’t know what it was.”

ALS wasn’t diagnosed right away. In December 2015, Quinlan had surgery on his left elbow for what was believed to be a compressed nerve causing the problem. But several months after the surgery, nothing had changed. Then he began to experience “foot drop” in his left foot, making him unable to lift up the front part of his foot as he walked.

Quinlan was diagnosed with ALS in the summer of 2016. Since then, walking has become a challenge, and he has continued to lose strength in his hands and arms. He has not lost strength personally.

Quinlan continues his work as a federal prosecutor, although courtroom appearances are fewer now. “I couldn’t ask for more support than I’ve gotten from my office throughout this whole process,” he says.

Married with two children, Quinlan says that “in the first few months after being diagnosed, it was scary, I’m sure, for all of us. I certainly envisioned scenarios worse than where I presently find myself. In that respect, I’m grateful and lucky.”

He’s also an Answer ALS participant, and serves on the Answer ALS Foundation board of directors, and he hopes his efforts and those of other Answer ALS participants lead to a breakthrough for the disease.

“I want to do my part to let the researchers advance their work,” he says. “I want to do what I can to help future patients have a hope that someday they will find a cure for this.”

Johns Hopkins’ Rothstein says it is crucial to use “the power of big data,” as Answer ALS is doing, “integrating multiple threads to try to do a better job of finding therapies and diagnostics for patients.”

The Answer ALS team believes the project is not only a milestone for people living with ALS, but may also be a template for battling other diseases.

“If we do that in ALS, there’s no reason to believe this couldn’t be done by others working on Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, and other neurologic injuries,” he says.

Top photo: In September 2018, Joel Shamaskin and his wife, Ann, participated in an Answer ALS walk in Rochester, N.Y. Photo courtesy of Joel Shamaskin.