How building robots together is opening doors and hearts

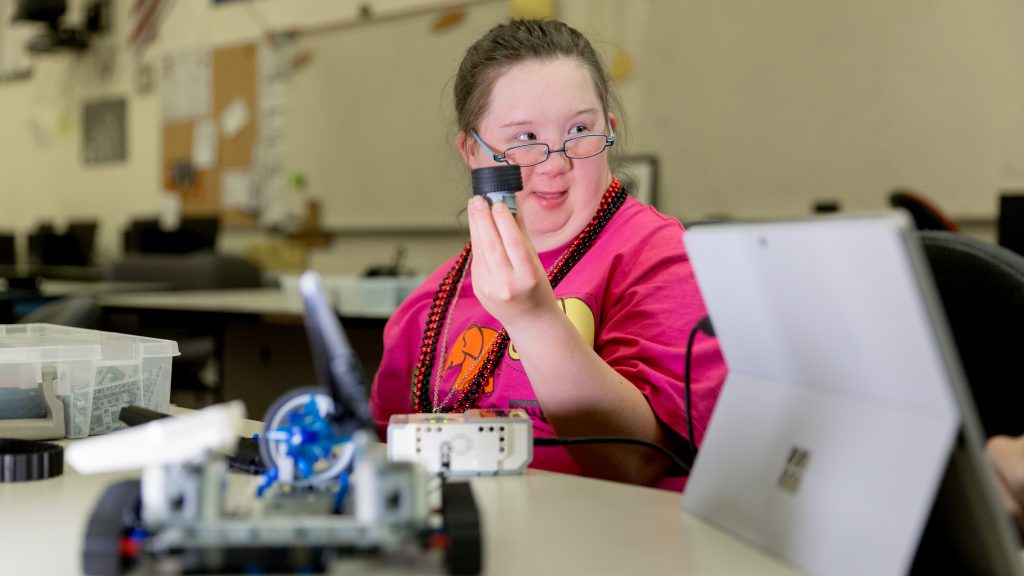

Pepper Swanson hands a small motor to her brother, Wyatt Gowen, and points to where she thinks it should go on the robot they’re building together in their high school computer lab.

Gowen asks what she’d like the robot to do. Does she want it to move forward? Turn around? Swanson, who is 18 and has Down syndrome, is the project’s designer and tester. She tells her brother she wants the tire on the front to spin slowly, to show off the blue star she’s put on the top.

When the pieces are in place, the robot starts with a whirr, plays a melody and moves forward.

“Yes! I love it!” Swanson exclaims, smiling.

The siblings, who attend Ballard High School in Seattle, are part of Unified Robotics, which pairs students with intellectual disabilities with other students to build robots and compete. The program aims to introduce students with special needs to STEM subjects, open doors to potential careers and foster friendships. In turn, high-achieving students connect with a population they may have little exposure to and gain leadership skills.

“I don’t think Pepper would have ever thought of robotics as a possibility or had real interest in it,” says Gowen, 16, who is also on the school’s FIRST Robotics team. “This gave her the opportunity to do it with me. It’s a chance to spend time with her, to build together. It’s also pretty fun.”

The program was started in 2015 by Delaney Foster, a student at King’s High School in Shoreline, Washington. Foster was a member of the school’s robotics team and wanted to find a way to involve her sister, Kendall, who has autism. She got the idea to start Unified Robotics after reading a story about Microsoft’s program to recruit and hire people with autism, part of the company’s broader effort to leverage an untapped talent pool and create opportunities for people with disabilities.

Microsoft provided the Surface devices the Unified Robotics teams use to build and program their robots, as well as mentoring and guidance as the program has grown. The company also hosts kick-off and robot-building events at its campus in Redmond, Washington, and Microsoft employees have served as judges and referees at the Washington championships.

“We’re proud to support Unified Robotics, which brings together two other Microsoft partners, Special Olympics and FIRST Robotics,” says Marcie Nymark, Microsoft’s director of brand partnerships.

“It’s an impactful program that promotes students’ interest in STEM and furthers our mission to foster diversity and inclusion.”

Microsoft’s support “has been a game-changer,” says Noelle Foster, Delaney and Kendall’s mother and Unified Robotics’ executive director. “It has taken the program to a different level.”

The initiative is modeled after Unified Sports, an inclusive program that pairs Special Olympics athletes with teammates for training and competition. Unified Robotics, which has a partnership with Special Olympics Washington, is now running in about 50 high schools around the United States, with each state hosting its own competition.

Washington’s 2018 championships will be held Nov. 18 at the Pacific Science Center in Seattle, where teams will compete in a tournament-style game by trying to push opponents’ robots out of a four-foot circle.

For Boris and Tatyana Bruk’s son Richard, school was a miserable experience. He has fragile X syndrome, a genetic disorder that impacts cognitive and emotional functions, and his parents struggled to find programs suitable for him. Then a special education teacher connected Richard with Unified Robotics, and he blossomed. He is now 24 and participating in the program for the fourth time.

“He loves it because it’s inclusive,” Boris says. “The regular students are with the special ed kids and that’s what he needs — attention. It’s one-on-one attention. Robotics isn’t the point. Inclusion is.”

Boris had tried engaging Richard in activities at home, from building things together to flying a remote-control helicopter. He wasn’t interested and was tired of spending time at home with his parents.

After joining Unified Robotics, Boris says, Richard became eager to learn and take on new challenges. He made friends and his confidence grew. The program provided a stimulating social outlet for him, and it gave Boris and Tatyana a network of parents with shared experiences.

“Parents and kids both have fun,” Boris says. “It all goes together, and it’s just kind of an amazing program.”

On a recent Saturday at the Microsoft campus, Richard is among teams of Unified Robotics students working on their robots during this year’s build event. He and his partner, Payton Ratzliff, have built the base for their robot and Richard is chatting excitedly about the upcoming championships. Ratzliff, a student at the University of Washington, says he appreciates the program’s ability to bring together a diverse group of participants.

“It gives me a chance to work with people I normally wouldn’t get to,” he says. “Everyone comes from a different background, so there’s always something to learn from everyone.”

At a nearby table, Einar Pedersen and partner Sam Hansen are working together for a third year. Hansen, who has autism and likes animation and filmmaking, has sketched out designs for the pair’s robot on a whiteboard. He admits he initially wasn’t interested in the program but says it’s more fun than he expected.

“I like hanging out with Einar and collaborating on ideas,” says Hansen, who attends Ingraham High School in Seattle. “I’m sort of the concept artist and he’s the programmer.”

Pedersen, who’s a member of the robotics team at King’s High School, saw Unified Robotics as a way to represent the team and give back to the community. He and Hansen bonded over their love of drawing, he says, and sometimes keep in touch outside of the program.

“I was able to gain a friendship with Sam and understand how some people with special needs might think,” Pedersen says. “I think that’s a really important aspect, gaining greater human knowledge and being able to relate to people. That’s what brings people closer together. That’s what this program does.”

It also enables students with intellectual disabilities to see their potential, says Unified Robotics board member Jeff Black.

“It encourages them to think a little bit beyond how they would have thought about themselves or maybe how their parents and teachers might have thought about them,” he says. “They’re the ones building the robots, and they’re very proud of what they do.”

For parents of children with intellectual or developmental disabilities, finding appropriate educational and social opportunities can be challenging. Raising their son, Jesse, who has autism, Seattle parents Lauren Feaux and Jose Oglesby were conflicted about enrolling him in programs geared to special needs. They wanted to put Jesse in activities he was likely to succeed in, but also didn’t want to limit his potential by placing him in programs aimed at people with disabilities.

“We felt that the regular programs should include people with disabilities. We didn’t like the idea of him being segregated,” Feaux says.

The inclusive nature of Unified Robotics appeals to them. It mirrors the real world, they point out, in which being able to work with a diverse range of people is important. Jesse got involved with Unified Robotics as it was starting up, helping recruit schools and participating on a team the first year. The experience, his parents say, gave him confidence and allowed him to develop his natural talent for organizing people.

“He could demonstrate leadership and get people together. He was able to work in a group,” Oglesby says. “That leadership role was really important for him.”

Jesse is now a sophomore at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He started an inclusive Ultimate Frisbee league at the college, drawing on the skills he gained through Unified Robotics.

“I liked helping out with everybody, and I liked having the opportunity to develop some recruiting skills,” he says. “I think it’s pretty important to relate to others who are different from us, and it’s valuable to have friends.”

To Noelle Foster, one of the most powerful aspects of the program is shifting perceptions about people’s abilities. She recalls a former participant who could not speak and had limited dexterity. The girl was unable to fit together the small Legos pieces in the robot kit, so her partner — looking for a way to involve her — gave her a job of putting a peg in a hole.

They’re the ones building the robots, and they’re very proud of what they do.

She struggled at first, becoming frustrated and agitated. But after about 45 minutes, Foster says, she managed to fit the peg into the hole. The girl was so excited she was snapping selfies and wanting to call her dad on Skype to show him, Foster recalls. By the end of the program, she had fit six pegs into a stick and put gears on the end of each so they could turn. She’d built her own robot.

“These other kids saw somebody who had worked so hard at something they take for granted,” Foster says. “It impacted them so much. They learned about tenacity.”

The girl’s mother stopped Foster as she headed to her car one day and thanked her for allowing her daughter to participate.

“Your daughter was a gift to the program,” Foster told her. “She made the biggest impact on everybody.”

Lead photo: Pepper Swanson, left, and brother Wyatt Gowen work on their robot. Images of Pepper Swanson and Wyatt Gowen by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures. All other images by Stephen Smith.