Students ‘create something really incredible’ in broader aim to help two cross-border cities thrive together

Orysya Stus is used to traffic. She’d seen plenty of it growing up in the Bay Area in California. But when she got to Seattle and drove downtown for the first time, trying to find a parking space was an exercise in frustration, exacerbated by all the other drivers desperately circling to find an elusive spot for their vehicles.

“This is definitely a problem,” says Stus, a graduate student who over the summer worked to help solve the issue. “It’s not that easy to get downtown if you have a car.”

A few hours north across the Canadian border, a group of undergraduate and graduate students worked to help the growing Vancouver suburb of Surrey make sure the bus system is operating the most efficient routes.

The Seattle and Vancouver metropolitan areas share more than their breathtaking scenery and growing tech industries: They both face rising housing prices, homelessness, increasing traffic – and also the great potential to work together to solve these and other urban challenges.

That’s why Stus was among 28 students from the University of Washington in Seattle and the University of British Columbia in Vancouver who used data science and analytics projects to tackle traffic, transportation and other metropolitan issues over the summer. Academic researchers and public stakeholder groups also participated in the projects in Data Science for Social Good programs, done with support from the Microsoft-sponsored Cascadia Urban Analytics Cooperative.

These are people who come from all walks of life, all different backgrounds and majors. And we were able to create something really incredible that can actually help someone.

The cooperative is part of the year-old Cascadia Innovation Corridor, created last fall when the governments of Washington state and British Columbia signed a formal agreement to deepen their collaboration in key areas like trade, research, transportation and education for the 12 million people living in the region.

“Last year we came together as a region to build something that we simply can’t create apart: an innovation corridor to create more opportunity and prosperity on both sides of the border,” says Microsoft President Brad Smith. “By linking our two cities together through cross-border collaboration, research, funding and educational opportunities, we will spur new economic activity and opportunity that creates a better future for everyone.”

Some of the students’ work is being shared at the second Cascadia Innovation Corridor Conference on Tuesday and Wednesday in Seattle.

In downtown Seattle, the vexing parking problem means drivers spend an average of 58 hours a year searching for a parking space, according to a recent study by INRIX. Seattle drivers rank fifth in the U.S., behind those in New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Washington, D.C., when it comes to the amount of time they spend looking for available spaces, according to INRIX.

The problem might be compounded by for-hire vehicles circling or “cruising” between fares. It’s something the city is looking at as it works to optimize downtown roads to alleviate traffic.

The University of Washington project used data from a portion of the 200 Bluetooth and Wi-Fi sensors in Seattle’s traffic signals to analyze millions of unique identifier addresses from mobile devices in cars. The identifier addresses were scrambled to be anonymized for privacy reasons so that no individuals were identified, and were re-anonymized daily so that no long-term patterns for an individual driver can be tracked.

The project was designed to generate a “Cruising Index” quantifying areas with a high concentration of circling traffic. The findings could help reduce congestion and perhaps contribute toward better and more effective use of the public right-of-way.

Stus, who is working on her master’s degree in data science and engineering, was among the fellows in the Data Science for Social Good program at the University of Washington’s eScience Institute working on the Cruising project.

“The very first thing we were able to show, and one of the main goals of our project, was to see whether this existing sensor grid that Seattle created could be repurposed for identifying cruising, and what we found is, yes it can be,” she says.

Most personally satisfying to her? “I worked with such great individuals for 10 weeks,” she says. “These are people who come from all walks of life, all different backgrounds and majors. And we were able to create something really incredible that can actually help someone.”

Another fellow, Brett Bejcek, penned a poem early on in the project that reads, in part:

Congestion is troublesome in Seattle

Getting downtown is such a battle

So our team’s going to do some fun math

To understand the circling path

Of people trying to find parking spots

Without paying the price of private lots

We have anonymized data of traffic flow:

An aggregated view of where people go

Steve Barham, data scientist for the Seattle Department of Transportation and the Cruising project lead, says students “collectively contributed expertise that the city does not have, for example, in applied math and working with big data. We had fellows that ate machine learning and different coding languages for breakfast.”

He says there will be “numerous ways” the city and others can put the data to good work. The information could be used by mapping apps to help predict the availability of parking, for example. Or it might be used to establish locations where transportation network companies, such as ride-sharing services, could have waiting areas established.

It’s exactly the type of progress the Cascadia Innovation Corridor was designed to foster, tapping the potential of the region’s best minds to enhance quality of life throughout the corridor.

“From the beginning, the fellows, the staff and the data scientists were excited about the challenge and public benefits the project could provide,” Barham says. “And throughout the summer, a synergy emerged as we talked with others also working in the transportation domain, such as the Orca Data Analysis Project, the Transportation Data Collaborative and Sound Transit.

There was synergy, too, between the University of Washington and University of British Columbia teams that met during the first Cascadia Urban Analytics Cooperative Summit in July. Student fellows, project leads and UW faculty got to learn about their counterparts’ work in UBC’s pilot Data Science for Social Good program.

“Part of the goal of CUAC was to grow beyond just the Data Science for Social Good summer program,” says Bill Howe, associate professor in the UW Information School, who directs UW’s participation in the Cascadia Urban Analytics Cooperative with the University of British Columbia.

“The result may be that 10-week summer projects will graduate to long-term projects, and some of those might graduate into flagship efforts that we do in the community.”

Raymond T Ng, scientific director of UBC’s Data Science Institute and a professor of computer science, says the cross-border effort holds promise for long-term sustainability solutions for both areas.

“From a Vancouver perspective, the nearest Canadian city is Calgary, which is way farther than our distance from Seattle,” Ng says. “It just makes a lot of sense from Vancouver’s perspective to be well-connected with Seattle, and I hope Seattle will also think it’s a great idea to connect with Vancouver. There is a lot of common interest – we are interested in transportation, we are interested in housing, we are interested in air pollution, earthquakes – those are really, truly regional issues.”

The city of Surrey, which is at a critical point in terms of transportation planning, appreciated the UBC fellows’ work on the city’s bus routes, Ng says. “It’s a younger city, and they’re exploring options based on data, and that’s very exciting from a data science and social good perspective,” he says.

Surrey doesn’t have Seattle’s traffic problems, but it wants to make sure they don’t happen. With a population of more than 517,000, Surrey is one of the fastest-growing cities in Canada, adding 1,000 new residents every month.

Saeid Allahdadian, a fellow on the Surrey Transportation Project team, says one of the things the team did to determine bus riders’ opinions was use the Twitter API to analyze existing comments from riders on what they thought about bus system efficiency, routes and stops. On the social media site, data is publicly shared, including users’ GPS locations.

“Of the million tweets sent every week in Vancouver, approximately 1 percent are geotagged, which means that over 10,000 geographic data points are being generated every week,” the team wrote in a preliminary report. “Analysis of tweets also helps to identify areas of the transportation network where additional attention is required. By extracting stop and route numbers from tweets to @Translink (the regional transportation authority) it is possible to build a map of trouble areas across Metro Vancouver.”

The team also built a graph model of Surrey’s bus network and compute indicators of connectivity and complexity for individual traffic analysis zones within the region, and plans to release an open source tool that lets transit researchers easily perform network analysis.

There is a lot of common interest – we are interested in transportation, we are interested in housing, we are interested in air pollution, earthquakes – those are really, truly regional issues.

Allahdadian, who also completed his doctorate in civil engineering over the summer, says the Cascadia Urban Analytics Cooperative projects are important for the future of the Cascadia Innovation Corridor.

“In addition to the urban and natural resemblance of Vancouver and Seattle as parts of the Cascadia region, there’s major traffic going on with people going back and forth across the border, those who work in Seattle and live in Vancouver,” he says. “That’s why if there’s a solution created in one region, it can be applied to another region.”

The key opportunity here is to go beyond a single city or a single university and to see what, in this case, a pair of universities and a pair of cities or metros are able to accomplish.

Thinking and working together as a region helps young innovators overcome boundaries and develop additional breakthroughs, a key strength of the Cascadia Innovation Corridor.

Jonathan Fink, UBC visiting professor of Urban Analytics, says the Cascadia Urban Analytics Cooperative is accelerating the partnerships between the two universities and their local cities.

“In some ways, the students provide a workforce and a problem-solving capability that cities may not have access to on their own,” says Fink, who has led initiatives related to smart cities and natural hazards, and who is former vice president for research at Portland State University.

“The key opportunity here is to go beyond a single city or a single university and to see what, in this case, a pair of universities and a pair of cities or metros are able to accomplish,” Fink says. “If you can take the same solutions and try them out in two cities, there’s the potential for coming up with general answers that can then be applied to dozens or hundreds of cities.”

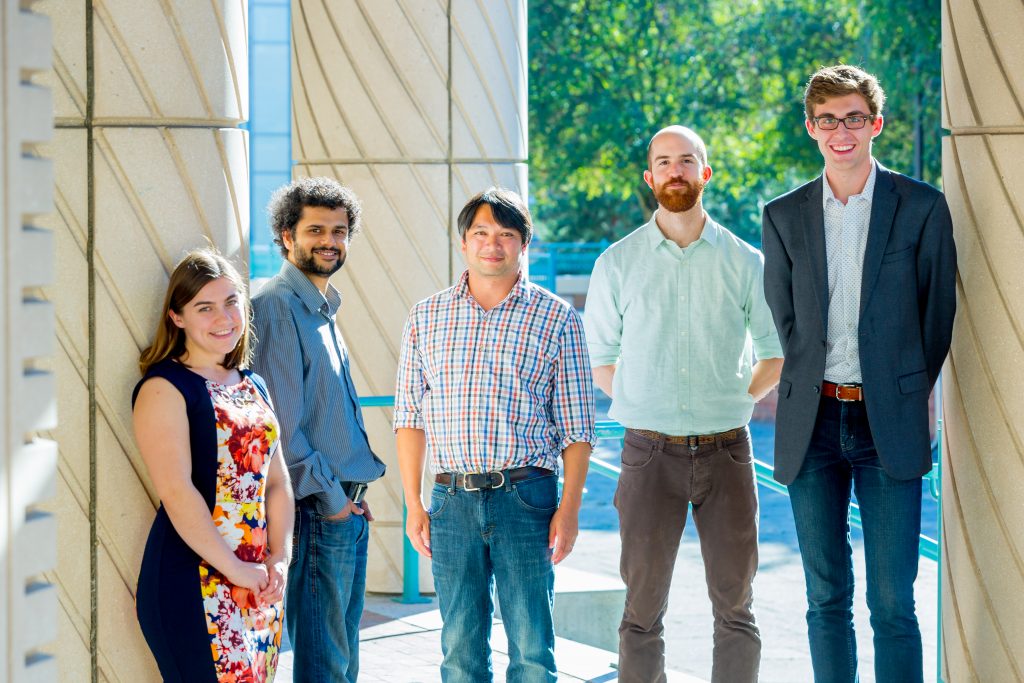

Top image: Steve Barham, center, data scientist for the Seattle Department of Transportation and project lead for the University of Washington Data Science for Social Good project on traffic sensor data and vehicle cruising, with project fellows, from left, Orysya Stus, Anamol Pundle, Michael Vlah and Brett Bejcek. Photo by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures.