The telltale tap: Soundscape app brings 3D audio map to pedestrians, gaining fans well beyond those with vision loss

A new 3D “heartbeat” tapping through stereo headphones is bringing pedestrians more independence and confidence while they navigate through cities.

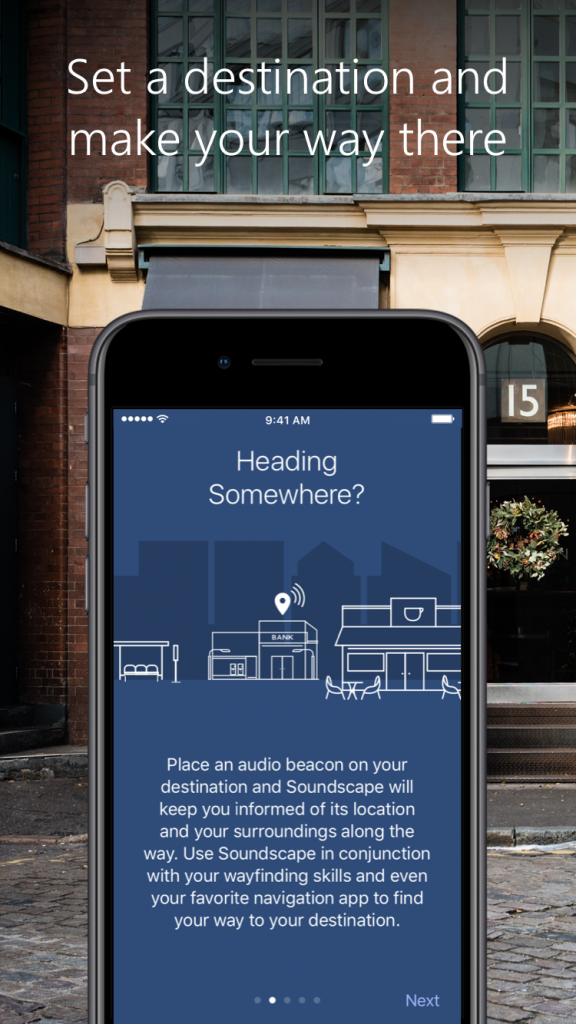

Three years in the making, Microsoft’s Soundscape app has been gaining fans from unexpected corners since it was released in February. The idea originated through a partnership with Guide Dogs UK and was geared toward helping people with vision loss. Audio cues guide users by making it seem like a steady beat is emanating from their destination, shifting through stereo headphones as they walk to help them form a mental picture of the location. It offers more independence than turn-by-turn mapping services. Verbal cues can be activated to call out shops, restaurants and other landmarks or explain where the user is and which direction they’re headed.

Now the app’s developers are discovering the philosophy of inclusive design that drove them is broadening Soundscape’s appeal.

The WE Schools program recently brought together a group of Tennessee high-school seniors and the band X Ambassadors, whose keyboardist is blind, for a lesson on inclusion and accessibility. The teens took the app on an audio scavenger hunt in Nashville to help them learn more about how it could help people with vision loss. By the time they’d reached their destination and were enjoying a private performance by the band, they were brimming with ideas for using Soundscape for themselves and friends – all of whom are sighted.

“Even though Soundscape was discussed as being for people who are blind, it took the students no more than two seconds to let us know that people with all sorts of different abilities and in different contexts could benefit from having a sound-based experience like this that’s not intrusive but is natural and comfortable,” said Amos Miller, a product strategist with Microsoft Research who co-created Soundscape. “We’re at the starting line with Soundscape, exploring using sound as augmented reality, which is a new concept for a lot of people, and it’s remarkable to see how this is applicable beyond the vision-impaired community.”

The audio beacon emits a low “rat-a-TAT, tat-tat” that moves within the headphones as the user turns toward or away from the site they set the beacon on. “It sounds like a heartbeat,” said Keishian Carrassquillo, one of the 12 seniors at West Creek High School in Clarksville, Tennessee, taking a class about education as a profession. Move directly toward the destination, and the audible cue becomes more overt, with a higher-pitched “ting, ting, ting.”

The audio is loud enough to compete with street noise – such as the six-lane road next to the parking lot where the kids started out, and the construction site they later navigated around – but unobtrusive enough not to interfere with conversations. The sound was designed to be harmonious and to convey a sense of motion and fluidity, said Jarnail Chudge, who created the app with Miller. Engineers worked to balance verbal cues and non-textual ones that don’t demand a huge amount of mental effort, he said.

Click “play” to hear the Soundscape beacon:

The steady tapping of the beacon proved a big help to Matthew Rife. The teen said he finds it hard to pay attention to directions when there are so many distractions in a busy city like Nashville, but “listening to the beat helped me focus.” Others said they would suggest the app to friends and family suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, attention deficit disorder and anxiety, because they thought it might alleviate sensory overload, as well as to those who are dyslexic or find it challenging to read maps. The kids even had ideas for setting beacons around their school hallways to help new students get around easier.

The experience broadened their understanding of the challenges faced by people with disabilities – with star power behind the message. X Ambassadors keyboardist Casey Harris, who was born with vision loss and learned to play piano by ear, told them about his childhood and how he navigates life as a rock star on tour. The band requires its venues to make a section accessible to people with all disabilities, and the video for their hit song “Renegades” features people with blindness weightlifting and hiking.

“Accessibility and inclusion really is not hard; it’s only hard in the minds of people who haven’t grown up with it,” Harris said. “And that’s why it’s so crucial for kids to be learning about it at this phase, is that it just becomes part of life. It’s not a special consideration, it’s just another consideration.”

Lead singer Sam Harris said watching his brother use Soundscape was “like looking into the future of accessibility.”

Soundscape can be used in the background in conjunction with other apps, such as a map that provides turn-by-turn directions, or Microsoft’s Seeing AI app that uses computer vision to recognize text – such as on signs – and speak the words aloud.

It’s not meant to replace other devices or mobility aids, but to complement them.

“This sidewalk is full of obstacles, so you’d still need a cane or a guide dog,” Jamie Wright said to the group, gesturing toward trees, garbage cans, potholes, sign posts and bike stands in the way. She helped lead the lesson using free resources provided by WE Schools, a service-learning program that helps teachers in North America get students involved in social causes. The “WE are One” curriculum, created with Microsoft, focuses on accessibility, and particularly the role of technology as a force for inclusion. On the scavenger hunt, Wright helped the kids feel with their feet, picking out the yellow bumps on sidewalks to alert them to intersections, and to note audible cues beyond Soundscape, such as a beeping crosswalk light.

“Soundscape was born out of a quest to figure out how technology can meaningfully change the experience of blind people,” especially since 90 percent don’t use technology as a mobility aid, Miller told the kids, with his guide dog, a black lab named Trevor, at his feet. Miller grew up on a kibbutz in Israel, slowly losing his sight to a genetic disease that left him blind by the time he’d finished university with a computer science degree.

“We use guide dogs, white canes, sighted guides, echo location and skills we develop, but there’s great potential for technology to have a bigger impact and to get more people out and about, with more confidence, joy and motivation as part of their daily lives,” Miller said.

Many people with blindness don’t leave the house on their own, and most that do venture out, with a guide dog or cane, are often limited to four or five routes they’ve memorized by heart. Soundscape aims to expand that universe and help more people with vision loss to explore, as well as to enrich those regular routes by calling out businesses along the way, allowing users to pop in for coffee, for example, at a café they may have never known was there.

“This option, the ability to choose what you want to do, has never really existed before, so it’s incredibly empowering,” Chudge said. “And that’s the point – we don’t want to tell people where to go, but rather to empower them by helping them understand where something is in relation to them, and they can decide how to get there on their own terms, in a more natural way, using their existing mobility skills. And at the same time, they’re building a whole new set of way-finding skills.”

Miller likened it to the difference between having a well-meaning sighted person grab his arm to lead him along, versus offering an elbow for him to touch and allow himself to be guided.

“The notion of Soundscape is that you’re in the driver’s seat, and the dog or cane is helping you to avoid obstacles, as it does best, but you can walk with your head high, aware of what’s around you and being in full control of your experience,” Miller said. “And when I walk with my wife or child, I hold on to their arm or to my dog, but with Soundscape I also have a broader awareness of where our destination is and what’s around and what roads we’re crossing, so I’m a participant and not just a follower.

“It’s a nuance, but from a sense of independence, it’s an important difference.”

With the phone held flat, the app’s “My Location” function tells users where they are, what direction they’re facing and what points of interest are nearby. The “Around Me” feature calls out landmarks in a clockwise direction, to help build a mental map of the space. The “Ahead of Me” does the same for what’s coming up on the road. The app calls out the remaining distance to the destination, as well. But users can also just keep the phone in a pocket and be guided by the audio beacon and automatic callouts, rather than bending over a map, Chudge said.

“That way our heads are up and we don’t feel self-conscious or that we don’t belong there,” he said. “It’s a completely different experience. As a sighted person, that’s enormously powerful and liberating, as it is for a person who’s blind.”

The app reflects the way it was created: Miller and Chudge took their team of developers and engineers away from the screens they were used to staring at and instead made them design it out in the field. They worked extensively with people with vision loss and with researchers who deal with spatial audio techniques to evolve the concept of using 3D sound. One result is that it can be used hands-free or with just one hand, leaving the other available to hold a guide dog’s harness, for example.

The app reflects the way it was created: Miller and Chudge took their team of developers and engineers away from the screens they were used to staring at and instead made them design it out in the field. They worked extensively with people with vision loss and with researchers who deal with spatial audio techniques to evolve the concept of using 3D sound. One result is that it can be used hands-free or with just one hand, leaving the other available to hold a guide dog’s harness, for example.

“It’s an outdoor experience, so we’ve been pounding the streets in all types of weather at all times, with a diverse group of individuals, to get to the heart of what matters and think about what the unarticulated needs are and how we can meet them to make a meaningful difference,” Chudge said.

Soundscape has helped engineers in unexpected ways, as well.

“It allows us to put augmented reality into the wild, in real-life situations where it enhances the human experience rather than detracts from it, and we’re learning from that,” Miller said. “This is a discreet device that you already are going to have with you, and it’s there to support you and not to interrupt.”

Since the technology is in its infancy, Soundscape is getting regular updates based on users’ feedback. And those reactions – along with collaboration with various nonprofits and businesses – are giving developers insight into how the app might evolve and what experiences can be incorporated.

“Creating this digital augmentation through sound is something we’ve really only been talking about for the past year in a meaningful way, and as an industry I think everybody is struggling a little with confining it to too narrow of a space,” Chudge said. “But what we’re seeing is that Soundscape is connecting users to their environment in a deeper, more significant and more intuitive way by working on enhancing human awareness and perception. It’s helping us grow as people and stretching our horizons.”

Top photo: Tennessee high-schoolers contemplate obstacles on sidewalks as they use the Soundscape app for an audio scavenger hunt in Nashville. Photos by Lindsey Grace.

To learn more, check out https://www.microsoft.com/inculture/musicxtech/x-ambassadors/.