America needs a sustainable blood supply. Mixed reality may entice a new generation of donors

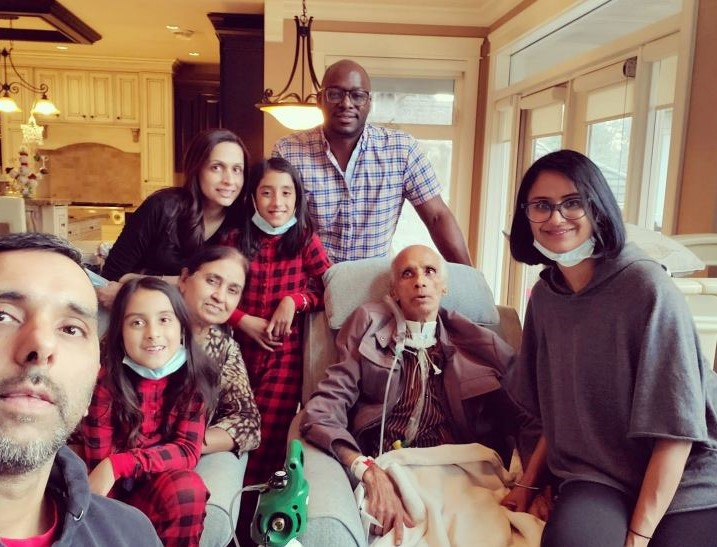

Weakened by cancer, Amar Singh Sandhu yearned for one more journey. He wanted to briefly leave the hospital to spend a final Christmas with his family. In the end, two strangers helped him make that homecoming.

He never got their names.

Days before the holiday, those two people had each provided a pint of their blood as part of the routine donations that help sustain community blood supplies. On Christmas morning in 2019, Sandhu, 69, received those two pints through a transfusion, boosting his energy for the special gathering.

“We were afforded precious moments with my dad that we will cherish for the rest of our lives,” recalls Harpreet Sandhu, who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. “It was his last Christmas at home. We will be forever grateful to those two blood donors.”

She has a rare perspective. As CEO of the Stanford Blood Center and chair of Blood Centers of America, Harpreet Sandhu has devoted her career to increasing blood donations across the U.S., where patients need blood every two seconds. As a daughter, however, she’ll never forget how blood transfusions – 14 in all – often enabled her ill father to simply open his eyes and interact with his family.

“These gave him the strength to keep going when he was at his weakest. Because of the generosity of blood donors, my dad was able to get the (blood) products he needed when he needed them,” Sandhu recalls. “It is so critical that we turn over every stone to figure out how to have a sustainable blood supply, so people like my dad and my family can have these incredible memories.”

To help meet that goal, Blood Centers of America, the largest blood supply network in the U.S., is partnering with Abbott, a global leader in screening blood and plasma donations, to make blood donations more appealing by wrapping the experience in mixed reality.

That technology is the centerpiece of a recently completed pilot study at select Blood Centers of America locations. The study is evaluating whether mixed reality – when used during blood donations – is safe, feasible and helpful in reducing the anxiety that some people experience during a donation.

Researchers also will use their findings to determine whether mixed reality encourages millennials and members of Gen-Z to give blood more often.

Why those specific age groups? During the past decade, U.S. blood centers have collectively lost about 30% of their donors under age 30, according to Sandhu. That decline has further imperiled a blood supply that, across the nation, often has about one-to-two days of available reserve, she explains.

The early results are promising. More than 200 donors have participated, donning Microsoft HoloLens 2 headsets to build an immersive, digital garden as medical teams collected their blood. The donors used only their eyes to plant virtual seeds that produced vibrant flowers in a mixed-reality world.

Meanwhile, the donors continued to interact with staff, remaining fully aware of their physical surroundings. And the device’s see-through lens ensured donors received a proper medical evaluation.

“It’s an ingenious application,” says Dr. Alex Carterson, Abbott’s divisional vice president for medical, scientific and clinical affairs, and a transfusion medicine specialist. “As a physician, I need to see the donors’ eyes to make sure they aren’t having a reaction. It doesn’t impede my ability to make sure they are safe during the donation.”

“I think this technology will be so impactful,” Carterson says. “It’s a way to make the donation a little more fun, a little more relaxing.”

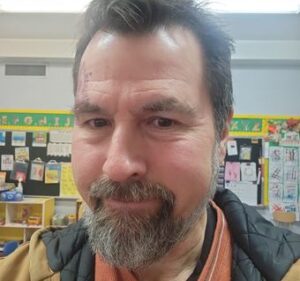

That’s exactly how Josh Pesin, a Brooklyn-based pre-school teacher, described what it was like to straddle the physical and virtual worlds when he recently contributed a pint of blood. He called the moment “a little fun.”

And without a doubt, Pesin is a tough sell. For years, he’s been reluctant to give blood because he often would faint during any type of phlebotomy procedure. When he heard that some friends were donating, Pesin steeled himself and said, “Let me try this again.”

On the day he dropped by a Brooklyn blood center, staff members happened to be asking visitors if they wanted to wear a HoloLens 2 and participate in the mixed reality experience. Pesin quickly agreed. There was no fainting.

“In the past, there was nothing else to do but just sit there and think about the fact that blood was being taken from me. And that was probably what made me faint,” said Pesin, 55. “This device made me focus on the virtual world – butterflies flying around and trees and nature. It distracted me.”

Even more, Pesin believes adding mixed reality to donations should coax people 30 and under to give blood more often because, he says, “they grew up in technology, so virtual technology will connect with them.”

That would be a welcome shift. Since 2020, the number of millennial donors in the U.S. has dropped by 12% while Gen-Z donors are down by 4%, according to Blood Centers of America.

Some of that decline was due to the temporary cancellation of blood drives at schools and workplaces during the pandemic. But other factors include a lack of education around the ongoing need for blood donations, a general lack of understanding about the process – some younger donors falsely believe blood can be artificially made – and the competing priorities of busy lives, Sandhu says.

What’s worse, only 37% of the U.S. population is eligible to give blood due to health or religious reasons. In fact, only 3% of the population gives blood each year, according to Abbott.

“There’s been a lot of compression on the blood supply as a result of having these younger donors exit the process,” Sandhu says. “The older generation is helping us sustain this one-to-two-days of supply nationally. This does not allow us much breathing room at all.”

When blood is in critically short supply, some scheduled surgeries may be delayed, some cancer treatments can be jeopardized, and hospitals can struggle to treat large numbers of people if mass casualty events further drain pints held in reserve.

“The blood supply is always on a precarious pathway,” Carterson says.

That’s precisely why Abbott approached Blood Centers of America to discuss how to use mixed reality to sustain a more reliable blood supply. They designed a soothing nature experience.

The scenery and seed-planting were based on research that found natural settings are the most favored digital environment for blood donors. And while virtual reality only allows users to sense a digital world, mixed reality lets users feel immersed in a virtual setting while they continue to see the real world.

Both Carterson and Sandhu have sampled the experience.

As a physician, Carterson says he can envision future medical use cases for mixed reality, perhaps for patients in pre-surgery settings to take their minds off their procedures, or maybe in pediatric offices to help kids work through fears of the unknown. Currently, some surgeons are using HoloLens 2 to help plan for complex procedures.

“I thought it was fantastic,” Carterson says. “It was not what I expected. It was very calming, but at the same time, having something to do, planting, took my mind off the donation. I really enjoyed it.”

“I felt the time went by so quickly,” Sandhu says. “It really allowed 10 to 15 minutes of calmness and refresh for me.”

Study investigators say they are encouraged that many people aged 18 to 39 enrolled because that’s the demographic Abbott and Blood Centers of America aim to inspire to become the next generation of donors.

“That is the spirit with which we have engaged our partners in this mixed reality – to make sure every single patient who needs a blood transfusion is always able to access that,” Sandhu says.

Just like her father.

“I often think about these blood donors who allowed my dad and my family to be together longer,” Sandhu says. “It’s an odd feeling to have complete, selfless strangers be the only ones to help your loved one in these most vulnerable moments.

“But that is just one patient’s story,” she adds. “There are so many other stories.”

Top photo: A blood donor wears a HoloLens 2 device at a New York City blood center. All donation photos courtesy of Abbott.