Educators and students now have a secure AI ‘scaffolding’ to support them in the classroom

Clare Prowse needs ideas for a “medical mystery” course for her 10th-grade biology students and has turned to AI. As the sample curriculum it created scrolls down her screen, she gushes over its bullet points and ready-to-use formatting — not to mention its suggestion of exploring a famous historical case she hadn’t thought of in years.

“Oh, the mystery of Phineas Gage, that would be a fascinating one,” says Prowse, who’s been using Microsoft Copilot for the last few months to help with “the work that adds to a full day of classes” as she teaches at Seattle’s O’Dea High School. “I might not use all of this, but it gets me thinking. It gave me the scaffold, and now I can go off and do this.”

From helping to draft course plans to inspiring homework ideas to jump-starting recommendation letters, teachers worldwide are reveling in the time savings they’re seeing with new AI tools such as Copilot. The technology is helping them focus more on their classrooms — and on the paradigm shift underway for learners as those same tools are rolled out to students. Educators of students from children to adult researchers are starting to change the way they teach, focusing more on the fundamentals of each subject and less on the clerical aspects of assignments.

“The impact of AI in education is huge,” Prowse says.

Ge Yan, a professor at Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business, began using Copilot for Microsoft 365 last November to take advantage of its assistance with various administrative tasks.

Yan likes to know his audience to help him tailor his teaching approach, so before every new class begins, he securely downloads the roster into Excel and breaks out demographics such as ages, genders, grade levels, majors, where students are from and more.

Even though he has a computer science MBA and more than two decades of experience creating spreadsheets and pivot tables, Yan found that Copilot in Excel could handle the job more efficiently. Being able to simply ask questions in the tool, rather than having to manipulate columns and cells between each query, helped his thought process flow more smoothly and naturally, Yan says, giving him a better picture of each incoming class.

Yan realized the same benefits could extend to students.

Educators have already begun piloting Copilot for Microsoft 365, and starting in April, higher education students 18 and older will be eligible, too.

So Yan started shifting his lessons to focus on the data insights his students should be contemplating instead of how to create pie charts to show what they find.

“Even for business majors,” who ostensibly do need to know how to build spreadsheets, Yan says, “we’re transitioning to teach them more of the what and why rather than the how to do that stuff.”

Yan was curious what his 8-year-old daughter, Tanya, would think about Copilot. She doesn’t share his interest in data or technology, but she likes birds, and was excited about a bird-watching assignment for school. So he downloaded a dataset from a national avian association.

“I said, ‘Do you know what’s the most observed species in Indiana?’ She said, ‘I don’t.’ I said, ‘OK, let’s type it in and ask.’ And boom, it’s the red cardinal,” Yan says. “There were a thousand observations in that file, and she was able to see the top three and their colors and sizes, and then I said, ‘OK, let’s go to the park and see if we can find those birds.’”

Instead of being given information and instructions, Yan was able to help Tanya extract knowledge from the database herself, unlocking new awareness as she saw the full context of where a falcon fits among the hundreds of birds in their state, he says. And instead of spending the afternoon in front of a computer learning how to create a pivot table, the father and daughter got to spend more time outside, pondering concepts such as why purple martins might prefer the climate in Indiana.

“It wasn’t spoon-fed to her by a parent or teacher,” Yan says. “It’s a learner-centric model. If I’m the one designing the pivot table and I’m interested in the color of the bird, then guess what, what the kids are seeing first is going to be the color of the bird.

“But now, as long as someone knows how to type and can translate the insight they’re looking for into a prompt,” Yan says, “they can do data analysis with Copilot in three seconds.”

Anne Leftwich uses the word “phenomenal” a lot when she talks about how AI has helped her reduce “the laborious minutiae tasks” that come with her job as associate vice president for learning technologies at Indiana University.

Leftwich started out using Copilot in Teams to provide transcripts, summaries and action items from meetings with faculty, staff and students. If she was late, got distracted by an urgent email, or had to step away to walk her kids to the bus stop, she’d prompt Copilot for a summary of the timeframe she’d missed and then could jump into the discussion without having to interrupt the flow by asking fellow participants to catch her up.

“I have too many tabs open in my brain, so this is helpful in keeping track of all those things,” she says. “And the nice part about Copilot (for Microsoft 365) is that it’s all staying within your unit’s data cloud.”

Before long, Leftwich started to “play with all the buttons and try all the things” — and that’s when the time savings really started adding up.

Being a teacher is never just about teaching. There’s planning, developing assignments, making rubrics, creating quizzes, writing recommendation letters, communicating with students and parents, researching, writing papers and presentations, and more. Leftwich says AI tools now help her complete administrative tasks in minutes that used to take hours.

For the self-described design-challenged professor — “I’m a former elementary school teacher, and everything I do tends to turn into rainbows and sparkles” — who has to create hundreds of presentations every year, Copilot in PowerPoint has made a big difference. Leftwich can pull an outline into the app, type in a few guiding prompts, and within moments Copilot crafts a polished, professional, cohesive design that she says she never could have come up with on her own, even if she’d spent hours working on it.

Clerical assistance aside, it’s the chat function with AI tools that causes the most consternation in education circles. New technology such as Copilot is based on large language models that have been trained by running huge amounts of data through algorithms, or sets of instructions, that helps them learn patterns and relationships in language so they can respond the way a human might when they answer questions and solve problems. But the systems can’t tell the difference between what’s real and what’s fake, so they can give inaccurate responses.

Prowse says her students started using AI in their schoolwork as soon as it became widely available through ChatGPT at the end of 2022. While she readily knows whether something is accurate or suspect when she asks it a biology question, she says, her students don’t, and need to be taught how to fact-check the results.

“But it’s my job to prepare them for life, and this is going to be part of their lives,” Prowse says. “Copilot will be one of those things everyone has. So I thought, I’d rather take this bull by the horns and get in there and talk to them about what it can do well and what it can’t.”

To make sure she’s assessing a student’s grasp of the material, rather than an AI program’s knowledge of it, Prowse gives the kids clear parameters for when and how they’re allowed to use the tools. She has certain assignments done in the classroom without devices, for example. Once O’Dea students get Copilot on their school accounts, she plans to ask them to share their tutoring chats so she can see the follow-up questions they ask and if those demonstrate they’ve understood the information.

Most exciting for Prowse, she plans to have Copilot help students with one of her favorite assignments: creating podcasts about ecological systems. It’s a popular project, but Prowse finds it frustrating to spend a biology class talking about intro music, the best Q&A format, or how to structure an episode so it’s less than two minutes long.

“They do the research, but then it can take them four whole class periods just to write the script,” she says. “So I’ll use AI to shorten up the time it takes on the podcasts and let me teach them more science — and they’ll have a really nice product at the end that they can be really proud of.”

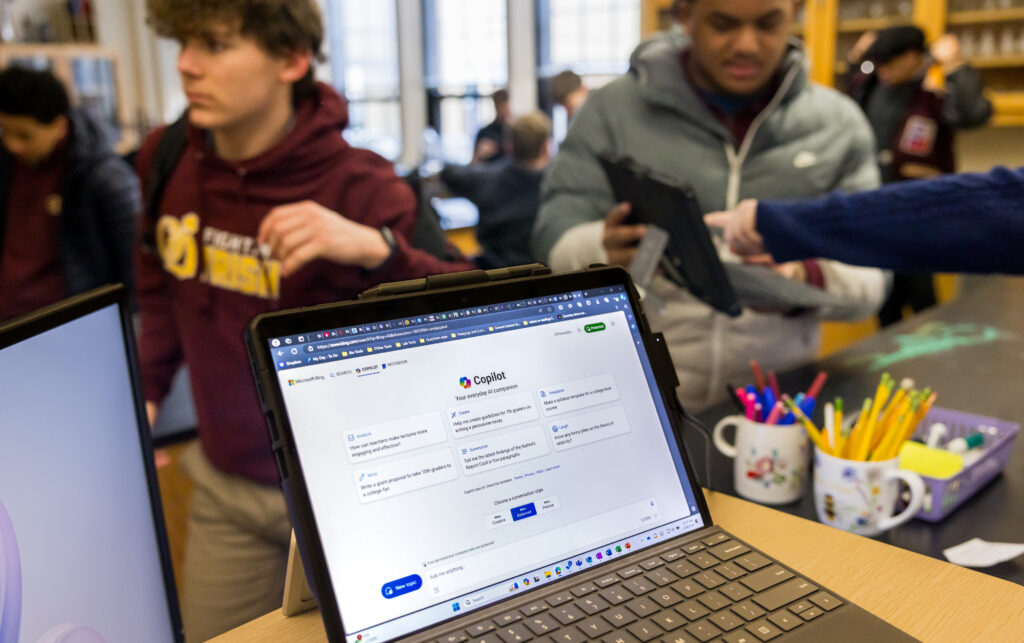

Educators and students 18 and older can use Copilot with their school accounts, giving them commercial data protection and a secure chat service. And Microsoft is expanding that option with a private preview program for younger learners in coming months.

While Prowse and others are cautious about the new technology, they say its impact on both sides of the education equation — teachers and students — is providing a springboard for more creativity and a framework that frees up time from organizational tasks to focus on the subjects being taught.

“And once the students learn how to use AI and get enough practice,” Prowse says, “the scaffolding thing will work for them, just like it works for me.”

Top photo: Clare Prowse, a teacher at Seattle’s O’Dea High School, helps students Hutton Leverett, Hugh Lear and Moriah Abner. (Photo by Dan DeLong)