For most parents, sleep is a sacrifice they accept during the earliest part of their child’s life. But for Francesca Fedeli and Roberto D’Angelo, sleep deprivation has been a constant for five years as they’ve taken turns in overnight co-sleeping vigils for their 8-year-old son, Mario, who has suffered potentially life-threatening seizures since he was 3.

Just recently, they’ve finally been able to sleep through the night.

“For about a month, we’ve regained that peace of mind that we had lost,” says Fedeli.

The much-needed breakthrough came from what D’Angelo, a 21-year Microsoft employee, and colleagues around the world worked to finish building in July at the company’s annual Global Hackathon, produced by The Garage. Their project, MirrorHR – Epilepsy Research Kit for Kids, was just named this year’s grand prize winner for the event.

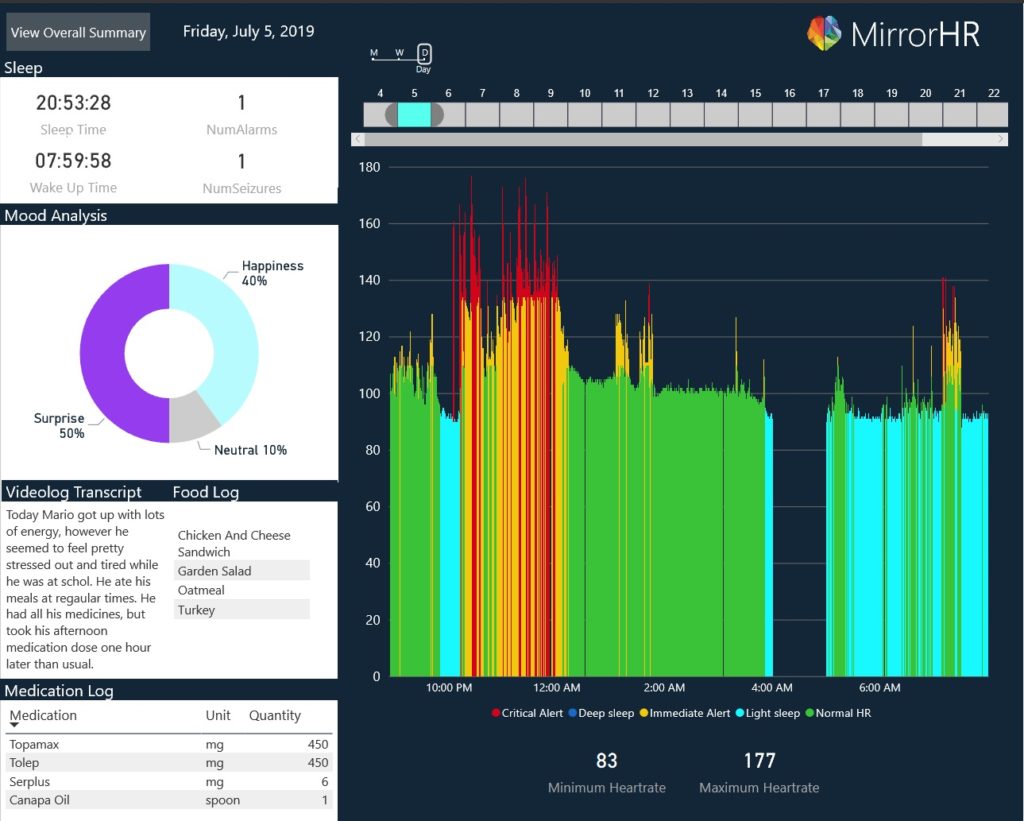

Mario’s parents are using the new system — a mobile app connected to a wearable device that sends alerts when anomalous activity might indicate a seizure — so they no longer have to hover over their son. It helps allay the biggest fear that a seizure could lead to what is called SUDEP, or sudden unexpected death in epilepsy.

“I see an amazing opportunity to make real what we’re trying to achieve,” says D’Angelo, who’s currently a director of program management on the Commercial Software Engineering team, based in Milan. “We have the ambition to make it real, to impact parents like me and kids like my son. This is the beginning of the journey.”

The 29-person hackathon team spanned the globe, with participants at Microsoft headquarters in Redmond, Washington, as well as in Washington, D.C., Canada, India and Italy, and was structured like a startup – with a mission. Members had expertise in many different areas including research and development, business, design and marketing, and they often worked in 24-hour cycles because of the various time zones.

The team worked together over about three months to develop the end-to-end, scalable proof of concept that is currently being tested by Mario.

Standing from left to right, Hackathon team members based in Redmond, Washington: Joel Gillespie, Maki Roggers, Mervin Johnsingh, Scott Kivitz, Robert Brais, Jessica Glago, Jacopo Mangiavacchi, Pritika Mehra. Kneeling/sitting from left to right: Scott Thompson, Rui Xia, Angie Maddox, Jun Taek Lee (Photo by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures) The rest of the team, not pictured: Aditya Singh, Akansha Gawade, Alessandro Bigi, Aroma Mahendru, Devagnanam Jayaseelan, Elena Terenzi, Giuseppe Martinelli, Guenda Sciancalepore, Hervi Icban, Juan Sepulveda, Melike Ceylan, Michael Schmidt, Mikayla Jones, Neil Gat, Ricardo Wagner, Roberto D’Angelo, Spencer Morris.

If a seizure is about to happen, parents can catch it at the onset and take immediate actions, such as preventing falls or other trauma and making sure the child doesn’t swallow vomit. It means there’s less likelihood the parents will have to rush to the emergency room or miss the seizure entirely. The biometric data and daily videologs are stored in a Microsoft Azure-powered FHIR Server. Machine learning and data visualization techniques are applied to this information to offer parents and doctors easy-to-read visuals and insights using Power BI tools.

“I believe that there’s so much potential to use tech for positive social impact, as long as we can truly engage with the people whose lives we want to improve,” says Pritika Mehra, the Redmond-based lead for the hackathon team, who just celebrated her one-year anniversary with Microsoft. “I’ve never seen so many different skills, personalities and nationalities come together so beautifully to create something.”

Mehra, a software engineer working on operating system biometric security in her daily job, says the project really showed her “the breadth of diversity and expertise that exist in this company.”

“What I value about this team so much is that I don’t feel like it’s just technologists solving a problem. So much of our team has lived this problem, through having autism, being stroke survivors or other personal connections,” she says. “The high level of empathy and learning, and the perspective that’s come from that, has really shifted the way that we think.”

Everyone on the team appreciated what others brought to the table — and the potential for their solution to help others.

“If we think about ways to help and include people with disabilities in our society, this is not just the right thing to do to bring everyone along, we can also get insights that are going to help everyone,” says Ricardo Wagner, Microsoft’s accessibility lead for Canada based in Toronto, who worked to share the team’s story.

Hackathon team members based in Redmond, Washington, showing how they worked on the project. Standing from left to right: Robert Brais, Scott Kivitz, Jacopo Mangiavacchi, Mervin Johnsingh. Sitting from left to right: Scott Thompson, Joel Gillespie, Jun Taek Lee, Pritika Mehra. (Photo by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures)

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological diseases. It’s marked by susceptibility to repeated, unprovoked seizures and affects more than 50 million people around the world, especially children. Many children with cerebral palsy have epilepsy.

“We are dealing with something huge, something that can really change lives,” Wagner says.

Mario’s diagnosis of cerebral palsy was established 10 days after he was born. His parents found out he’d suffered a perinatal stroke, which severely injured the right half of his brain, making him unable to control the left side of his body. But because they found out so early, D’Angelo says, they were able to begin rehabilitation immediately, engaging Mario in stimulating games and other therapies to help him regain his motor skills.

Mario in kindergarten doing bimanual activities, playing with a rolling pin. (Photo by Andrea Ruggeri)

In their research early on, D’Angelo and Fedeli were hampered by a lack of information on childhood strokes like the one their son suffered. But since then, they’ve been continuously learning from other families going through what they were experiencing, as well as from medical professionals.

They founded FightTheStroke back in 2014. Both were driven by the conviction that in order to help their son, they had to “help every kid in the world like him.” The foundation is working toward a new ecosystem that includes independent living for kids who have cerebral palsy, a group of disorders that affect muscle coordination and balance, usually caused by damage to the brain before or at birth.

Over the years FightTheStroke has helped establish a pediatric Neonatal Stroke Center at the Children’s Hospital Gaslini in Genoa, Italy; created rehabilitation camps for kids; and promoted scientific dissemination and platforms to spread awareness.

Roberto D’Angelo, Francesca Fedeli and their son Mario at TEDGlobal 2013 in Edinburgh, Scotland. (Photo by Ryan Lash)

As Mario got older, his epilepsy became harder to control. Fedeli and D’Angelo tried solutions claiming to detect seizures, but none worked for him. It took a toll on the family.

“Mario looked to his parents as mirrors. So when Francesca and Roberto realized they were reflecting their sadness to Mario, they wanted him to see the best from them instead,” Wagner says. That idea led to the name MirrorHR for this project, and also an earlier project called Mirrorable, which focused on an interactive platform geared to rehabilitative therapy at home.

“We were so uncertain of Mario’s future. When he was 3 and he had the first seizure, we went to the ER, his life was at risk. From that point we began to know the burden of epilepsy,” says Fedeli, who had suffered earlier miscarriages and had to spend months bed-bound before giving birth to Mario. “Apart from the risk, it’s the fear and fact that you lose your peace of mind. You can’t sleep anymore because you’re always checking if your son is breathing.”

Fedeli and D’Angelo took turns monitoring their child all night long. They’ve gone to the emergency room 24 times in the past five years.

“A couple of years of no sleep, I can guarantee is no good,” D’Angelo says. “But we can reframe this. We know this problem so well, we can do something. It’s worth trying. The probability of failure is probably 99%. But the 1% chance is worth my life.”

So the reframing focused on a solution that would allow parents to get some sleep and wake them up when a potential seizure was detected. By identifying tell-tale patterns and triggers, the team has helped parents contain seizures and avoid traumatic rushes to the hospital.

Hackathon team member shows early prototype of MirrorHR anomaly alert (Photo by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures)

For Mario, routines matter. Going to sleep at the same time each night and reducing stress also help reduce the potential for seizures.

“We practice continuous mirroring in our family. Once we feel safe, secure and confident, Mario can keep trying,” Fedeli says. “Our son has regained confidence and is enjoying every day of his life.”

The family won’t be alone as they face future obstacles — and they’re grateful for the jumpstart they have on this problem.

“We couldn’t have had enough resources to do this in such a short time,” Fedeli says. “The fact that we can count on the right professionals has been crucial in these developments.”

The team wants to use machine learning as they get more data, so they can generate more intelligent insights to help parents and doctors better nail down what may be triggering these seizures. Then, they could adapt accordingly, by calming down patients, improving the environment or staying close when there are indicators for a seizure.

“I truly loved working on this project,” Mehra says. “I’ve learned so much about how you can bring people and skills together through a central mission to create something against all obstacles. All this is very much possible because Microsoft is supportive about giving employees resources to work on projects like these. More than that, they have incredible channels to help to find these people, and foster, support and encourage you.”

Wagner, who’s been with the company 12 years longer than Mehra, couldn’t agree more.

“My personal mission in life is to help people with disabilities. That’s the reason I work for Microsoft, to empower every person on the planet,” he says. “It’s a privilege to work on this. This one was very special. Everyone was committed to make it happen.”

Mario, 7, at the first edition of FightThe Stroke’s intensive sport/rehab camp in 2018, looking at his sport trainer at the basketball court. (Photo by Eleonora Rettori)

Like other kids his age, Mario is back in school. While he still faces many challenges, he’s been able to enjoy the benefits of rehabilitation and neuroplasticity.

“As a couple they have a limited time on the planet,” Wagner says of D’Angelo and Fedeli. “Every day is an opportunity to empower Mario.”

“My son is my coach. He’s helping us every single day to look at things through his eyes,” D’Angelo says. “Disability can be a strength. Now I have the proof, it’s true. What we have is a gift and what we miss is just an opportunity for improvement. We maximize the strength of each person, mix it and balance each other in order to be stronger together.”

Lead image: Francesca Fedeli, Roberto D’Angelo and their son Mario (Photo by Andrea Ruggeri)