Her children had grown up under frequent bombing in eastern Ukraine for the past eight years and would automatically — and calmly — run to an inner corridor for shelter whenever they heard the telltale whoosh. So when even they started getting scared this past February, Lyubov Volodimirivna Dubohray knew it was time to flee.

The family of four squeezed onto an evacuation bus and then a train heading west, one of the last that managed to pass along damaged rails. Later they learned that the very next morning, the train station had been bombed.

“And still we were standing,” says Dubohray, whose family managed to make it more than a thousand kilometers (about 640 miles) to a kindergarten classroom near the Polish border being used to house displaced people from different regions around Ukraine. “We have been living here as one big family. They want to reopen the kindergarten, but I don’t know where to go yet. We don’t know what will happen next.”

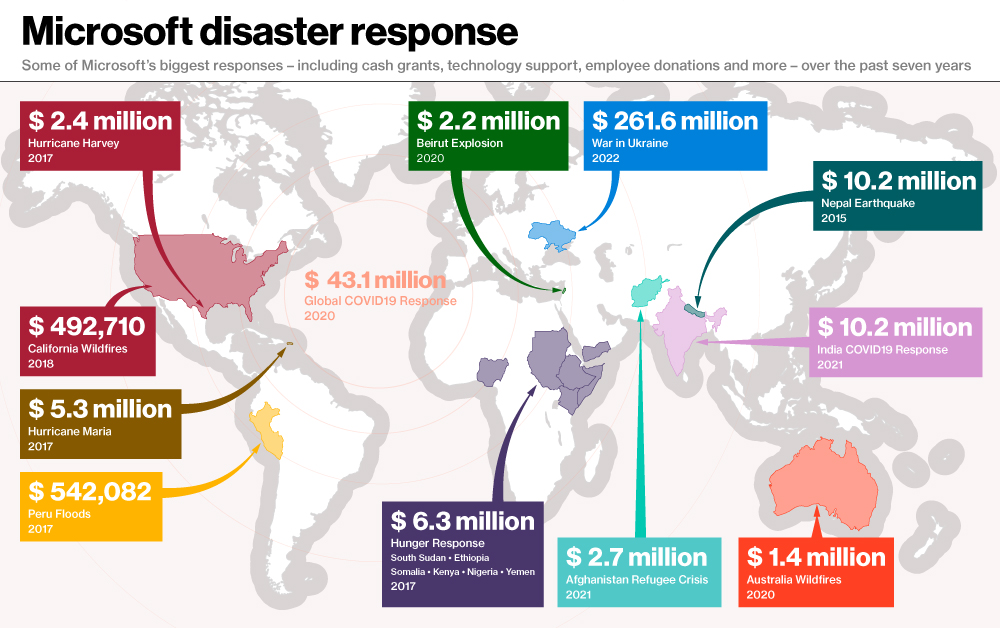

One thing the Dubohray family does know is that it’s getting prompt help from Polish Humanitarian Action, an international nonprofit that has been working in Ukraine since 2014 and this year has given thousands of Ukrainians the financial support to buy food, medicine and clothing while they look for new jobs and homes far from the fighting. With Microsoft’s support — among the tech company’s disaster response efforts around the world, which now include Hurricanes Ian and Fiona — the organization was able to react nimbly this past spring to assist displaced people along the Polish border by equipping mobile teams with tablets, software and apps.

Polish Humanitarian Action worked with Microsoft to equip its staff and mobile teams with tablets, software and apps so they could react quickly to assist displaced Ukrainians. (Photo by Roman Baluk/Polish Humanitarian Action)

“When you get off the train, you might have enough savings to get to a group home and support yourself for a little while, but that usually dries up quickly, and it’s important that help be available as soon as that happens,” says Helena Krajewska, a Polish Humanitarian Action spokesperson who met the Dubohray family in June. “People were applying to us for help without much hope, because they hadn’t received assistance from others, and they were surprised to receive support so quickly from us.

“Technology played a big role in this,” Krajewska says, “because it sped up the process and allowed us to process a lot of applications at the same time.”

Lyubov Volodimirivna Dubohray and her son (Photo by Roman Baluk/Polish Humanitarian Action)

The impact of technology during times of crisis has always been clear and has become even more critical in recent years. Global warming has brought more catastrophic storms and floods affecting hundreds of millions around the world. In just the past few weeks, Microsoft has activated giving campaigns to help those affected by Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico and Hurricane Ian in Florida. Disaster response teams are providing technical assistance and resources to organizations in need.

The coronavirus pandemic brought unprecedented global challenges as well, and Microsoft’s disaster response efforts have grown accordingly. The company has honed its processes to make a timely difference in the communities where it operates, not just through software and hardware donations but by harnessing the skills of a vast global workforce made up of people longing to help with their time, talents or money.

“Unfortunately, we’ve had too many opportunities, over the last few years particularly, to build our muscles for disaster response,” says Kate Behncken, who’s been leading Microsoft Philanthropies since 2019 and saw employee giving skyrocket for the COVID-19 and Ukraine response efforts. “The level of energy across the company for the social impact work Microsoft does is at an all-time high. Employees will often say it’s one of the things they value about working at the company, the fact it values both profit and purpose and invests in both.”

The seriousness with which the company takes its role in society — executives often say giving is “in our DNA” due to the influence of Microsoft founder Bill Gates’ philanthropic mother, Mary Gates — is what drew Lena Ryuji there 15 years ago. She now leads philanthropic engagement in Japan, a country that has had to cope with more natural disasters than most, so she keeps the disaster-response team on speed-dial.

Ryuji was working with nonprofits to help the most vulnerable in the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami when a Japanese state government official reached out. It was taking days to issue critical reports to the public on the radiation levels after the Fukushima nuclear accident, as inspectors used paper and fax machines to report from dozens of monitoring posts around the country. Within a few hours, Ryuji and her colleagues pulled together a team and had Microsoft engineers working on the problem. When she woke up the next morning, the system was in place with a secure and mobile cloud solution.

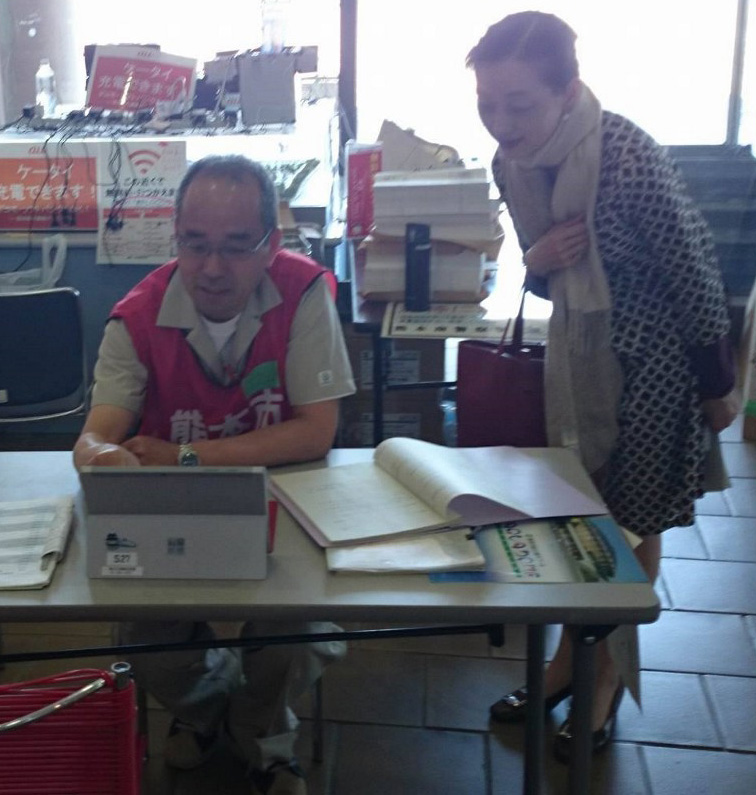

Lena Ryuji, right, who leads Microsoft’s philanthropic engagement in Japan, and Tadayuki Nakamura, left, a government official, using the cloud to connect evacuation centers after the Kumamoto earthquake in 2016 (Photo provided by Shugo Ikemoto)

That experience wasn’t an anomaly, Ryuji says, adding that employees have jumped in to help with mudslides, floods and other emergencies that have taken place every year. And just as Microsoft is helping governments and first-responder organizations prepare ahead of time for disaster relief, it has refined its own methods to be more effective. Each department has assigned individuals who understand how the company and its employees are equipped to help, how to reach the right contacts and how best to work together so it’s not a scramble in the midst of a crisis, Ryuji says.

“I really appreciate that we as Microsoft are also prepared, that we have a process that’s handled centrally and that we are trained on,” she says.

Erich Pfeiffer was working for Microsoft as a principal consultant at the U.S. military’s Ramstein Air Base in Germany last year when the Taliban’s seizure of Afghanistan led to the largest air lift in U.S. history. He watched as a runway was turned into an impromptu tent city to house a steady stream of unexpected refugees.

“I went home late that Friday night and thought, ‘We have a disaster response unit in Microsoft, so I wonder if we can do anything to help,’” Pfeiffer recalls.

By the end of that weekend, he’d gotten a mission approved to help with the Afghanistan evacuation. Work began Monday morning to create a digital system to track and manage housing, food and ration cards, and more for the thousands of refugees suddenly living on the base.

“There were people who had been on planes for 15, 18 hours, just come out of a war zone, and while they’re waiting to be processed they don’t have a bed to sleep in and they’re just sitting on the ground for hours,” Pfeiffer says. “So the faster you can get them processed, the faster you can get them settled down to recuperate.”

Engineers, cybersecurity experts and a whole infrastructure team from northern Germany all rushed in to help, giving up sleep themselves for days, Pfeiffer says. They built an application and set up dozens of consoles that helped track, locate and reunite families amid the mayhem and more than quadrupled the number of refugees getting processed each hour to about 250, only stopping because that was as fast as tents could be set up.

Microsoft employees Michael Vasiloff, Matt Hillman, Erich Pfeiffer and Stephon Westfall helped create tech solutions that moved tired refugees arriving from Afghanistan more quickly to the tents being erected for them at a U.S. military base in Germany. (Photo provided by Pfeiffer)

“We were empowering the people processing them to get these folks moved through to a better place where they could have a better life,” Pfeiffer says. “There isn’t a single one of us who wouldn’t do it all over again. And in fact, we all are. Fast forward to February and every one of us is back at it helping displaced people again, but from Ukraine this time.”

Pfeiffer and his colleagues have harnessed their experience to create volunteer and refugee management systems around Europe, helping Ukrainians find housing, join their host countries’ healthcare systems and more. Depending on the situation, they volunteer their hours or bill Microsoft’s disaster response team as a member of a formal company engagement, Pfeiffer says.

“Everything Microsoft’s disaster response team does — everything — is at zero cost and has to meet one simple criteria: It has to relieve human suffering,” he says.

Beyond the free disaster-response assistance, Microsoft gave $2.5 billion in grants and discounts to more than 300,000 nonprofits last year alone. And the new Microsoft Cloud for Nonprofit provides solutions for activities every charitable organization around the world has to manage — fundraising, program design, volunteer management and the like — so such groups can respond faster and more efficiently, especially during times of crises.

Microsoft also matches employees’ volunteer time and cash donations through the Employee Giving program, which is almost as old as the company itself and has provided $2.49 billion in assistance over the decades.

It uses its wide reach to partner with customers as well. Xbox, for example, teamed up with the gaming community to raise millions of dollars for organizations including World Central Kitchen, which has been feeding people all over Ukraine since the day after the first missile hit on Feb. 24. LinkedIn gives grants to nonprofits that help newly settled refugees find jobs that match their skills, and it created a site with tools for displaced people that’s available in seven languages. Microsoft Advertising offers ad grants on channels including Yahoo and MSN. And Bing provides awareness on the home page and directs users to fundraisers and other ways to help.

While the war in Ukraine has dominated news in 2022, there are more displaced people in the world than ever before, with 100 million refugees fleeing wars and natural disasters. Tech companies are uniquely placed to help, especially since technology now touches every aspect of life, says Juan Lavista Ferres, Microsoft’s chief data scientist and the director of the AI for Good Research Lab.

“There are problems that only artificial intelligence can solve, and more than 90% of AI experts work in the tech and financial sectors, not the nonprofits or governments,” Lavista Ferres says. “So we as a company have a responsibility to use our knowledge to help the world.”

Juan Lavista Ferres, chief data scientist

Teresa De Los Santos, account manager

The need has never been greater than in the past three years. As Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said at the beginning of the pandemic, the world saw two years’ worth of digital transformation within two months as country after country went into lockdown and turned to technology to communicate, work and study.

The company’s AI for Good team worked with health departments to develop dashboards that tracked and predicted COVID-19 cases and the efficacy of various preventions and treatments, while continuing work on projects such as one that uses satellite data and machine learning to help communities analyze buildings’ vulnerabilities and be better prepared for disasters

An account manager for Microsoft in Los Angeles, Teresa De Los Santos knows how to take care of customers and make sure they get the resources they need from across the company. When she volunteered for her first disaster-response mission, she found her experience translated well into crisis management.

“It’s similar to a doctor going to a war-torn area and helping victims heal, or a hairstylist going to the streets of LA to give haircuts to the homeless,” De Los Santos says. “I’m transferring my skills from my day job into being a mission coordinator.”

First, De Los Santos organized a team of Microsoft engineers to quickly help a nonprofit working in Ukraine handle a software security issue. Then she pulled together technical support and free Microsoft 365 subscriptions for journalists with a Ukrainian media foundation, which no longer had any revenue to pay for the tools needed to communicate and report.

“When we were meeting with them, you could hear sirens, and it was scary,” De Los Santos says. “Knowing that I facilitated everything and was able to help them do their job in the midst of all these bombings gave me a sense of satisfaction, that maybe I did something good for the rest of the world.

“It’s not like I work for a nonprofit,” she says, “but being with Microsoft and getting the opportunity to make an impact that’s different from my regular job — I’m lucky.”

Top photo: Lyubov Volodimirivna Dubohray and her son at the kindergarten they’re temporarily being housed in near Ukraine’s western border, more than a thousand kilometers (about 640 miles) from the home they fled amid bombing attacks in February (Photo by Roman Baluk/Polish Humanitarian Action)