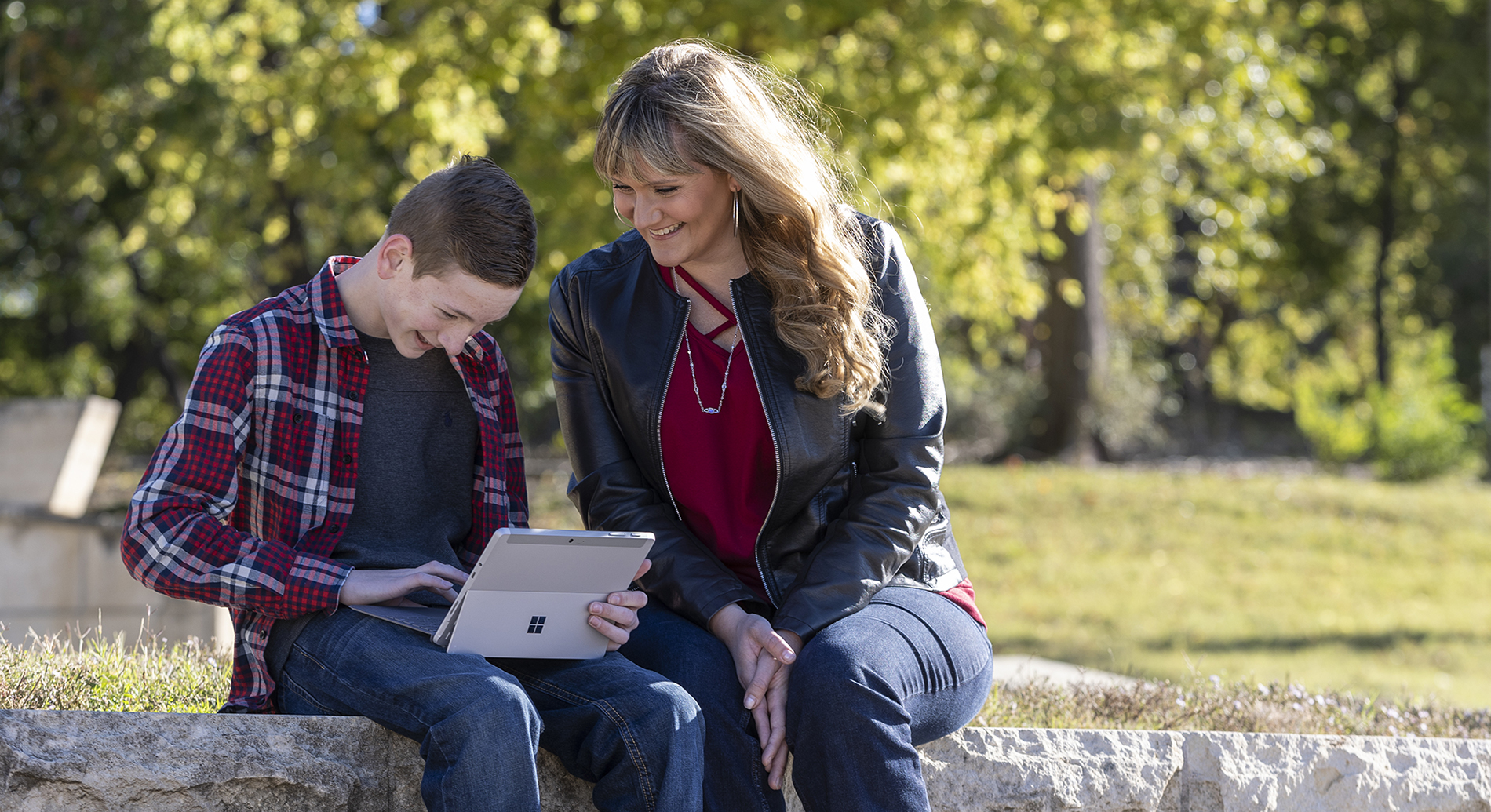

Eleven-year-old Graham Young is proud to have gotten 100% on a recent book report and is excited about the poster he just made to advertise his fledgling lawnmowing business in his neighborhood.

But what really puts a sparkle in his eyes and turns a shy smile into a wide grin? He did it all himself. With a neurological condition that makes him unable to read or write, Graham has been using tools such as Immersive Reader and the Windows speech-to-text feature over the past year to help him fully participate both in and out of school.

Whether it’s neurodiversity, physical disabilities or the challenges of poverty, teachers like Graham’s are finding that tech tools can be used as leveling blocks to help address many different kinds of inequity in schools. The new edition of the Windows 11 operating system, Windows 11 SE, and the lower-cost devices it supports, such as the Surface Laptop SE and others from Microsoft partners, join a range of learning technology aimed at helping educators give students the individualized support they need to succeed.

“We have a better understanding of the potential and limitations of technology than we ever had before,” says Joseph South, chief learning officer for the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE). “We’ve pushed what it can do and scaled it more than we ever have, and that’s given us new insights.”

One of those insights is the importance of high-quality tools.

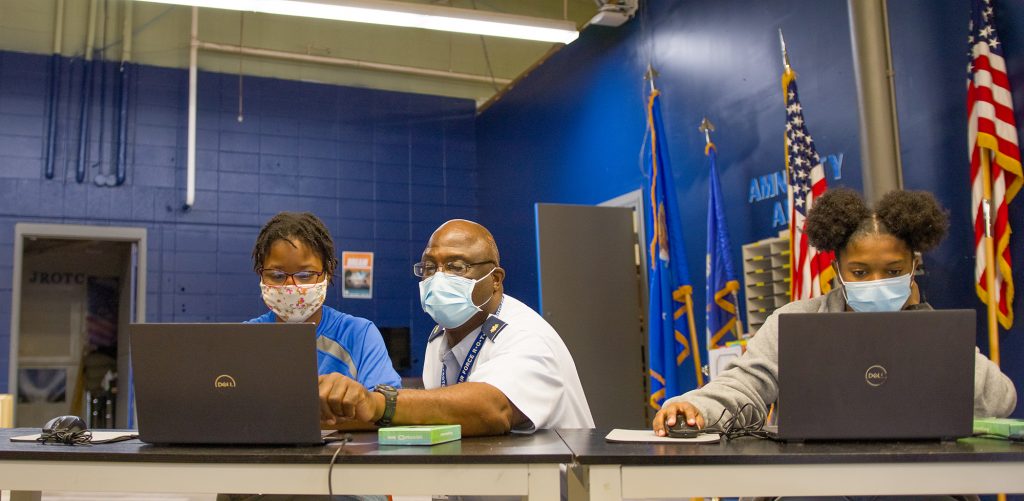

All 340 students at Aberdeen High School in rural Mississippi — a school that gets supplemental federal funds because of high levels of poverty — were given web-based devices when the pandemic hit last year. But those proved ineffective without home internet access, which about half of the students and even many teachers didn’t have.

Major Allen Williams, the Junior ROTC instructor at Aberdeen High School in Mississippi, with students Michaela Lenoir, left, and Trinity Harris, right (Photo by Alex Wilson, New Honor Society)

And Major Allen Williams, who had just taken charge of the Junior ROTC program there, quickly discovered that even when they were online, the laptops didn’t have enough computing power for the advanced-placement computer science courses and e-sports teams he had created.

But Williams fights fiercely for his school, where he says nearly all of the students are Black and two-thirds are girls facing “inequities that are the same old story throughout our society where women and girls aren’t promoted, especially where technology careers are concerned.” So the Mississippi native and 25-year U.S. Air Force veteran quickly obtained a grant for two dozen Dell laptops that are powerful enough for all of the robust apps required for his classes and that give students experience with the Windows operating system and Microsoft 365 software they’re most likely to use in later jobs.

Now one of his students has started college — pursuing a career in tech that she’d never considered before — and this year another high school senior and three juniors are following in her path.

“You have to practice the way you’re going to play,” Williams says. “We have to train our kids in an environment like they will encounter when they go into the workforce.

Major Allen Williams, the Junior ROTC instructor at Aberdeen High School in Mississippi (Photo by Alex Wilson, New Honor Society)

“Too many times we don’t have high enough expectations of our kids. But when we raise the expectations and raise the capacity within the institution to provide the tools to meet those expectations, these kids blow it out of the water.”

Students in rural areas in particular can be left out if there’s no German language or advanced-math teachers available, for example, but tech tools now offer “possibilities beyond your classroom or the limits of your town,” South says. “Technology provides robust access to high-quality resources — educators, expertise, opportunities — that transcends geography, which for most of us is only a few miles wide where we live, work and go to school.”

Wichita Public Schools in Kansas began creating virtual field trips called “Edventures” during the pandemic that are providing rich experiences for many kids — including those who might not have been able to take actual trips for physical or financial reasons. Dyane Smokorowski, the school district’s coordinator of digital literacy, networked to find museums, companies, authors, actors and teachers to help her pull off 330 such events last schoolyear and about 30 so far this schoolyear.

She aligns the Edventures to the content kids are studying in each grade and makes them free to anyone, hosting as many as 10,000 students at a time through Microsoft Teams Live Events.

In October, for example, fifth graders studying the steps into the American Revolution got to interview an actor who played the role of a tavern keeper in 1775 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, using artifacts to paint the picture of life for kids in that era. Fourth graders studying biodiversity got a virtual lobster-boat experience, learning how Maine’s aquaculture differs from the agriculture of their landlocked state.

We have to train our kids in an environment like they will encounter when they go into the workforce.

“Our students in Kansas don’t have personal references to things like colonial America, but physically taking them to Boston is not an easy thing to do,” Smokorowski says. “But I can bring New England to my kids virtually and build authentic experiences, providing equity for all and a learning experience that every student can share, not just enrichment for the gifted or wealthy.

“When we look at equity, the real goal is to remove barriers,” she says.

The district’s 96 schools logged more than 40 million Teams activities — chats, meetings, assignments and the like — last schoolyear, when teaching was done remotely for the greater part of the year. The deployment of new devices and technology went so well — helped in large part by teams of students given technical training — it held the largest summer school it’s ever developed, helping to counter the “learning loss” from the pandemic’s disruption, says Rob Dickson, chief information officer for Wichita Public Schools.

The crisis provided a good delineation for “showing what 21st century learning is supposed to look like,” Dickson says. “What we don’t want our teachers to do is go back to the pre-pandemic classroom.”

Schools in many areas are saying they’ll never return to exclusively in-person parent-teacher learning conferences for example, ISTE’s South says, after last year’s introduction of virtual meetings saw participation skyrocket — especially among parents with long commutes or working hourly jobs or unusual shifts that hindered them before.

Educators are using technology such as social media and other platforms and forums to connect and share ideas as well as work together on combined projects, South says. The results are sophisticated developments that promise to provide permanent benefits going forward, he says.

When we look at equity, the real goal is to remove barriers.

One teacher wanted to help students learn about art and museums and also build relationships with each other while stuck at home. She had the kids create displays — one put pieces of her artwork on the wall of a stairwell — and then use Flipgrid to give each other “museum” tours. Elsewhere, school districts around the country created a unit together based on United Nations sustainable development goals. The students tested the water in their different communities and compared notes to learn how quality issues varied depending on geography.

“The technology was stable and reliable and allowed this connection and data sharing,” South says, “but it was the imagination of the educators that came up with such a compelling activity that broadened the perspective of those students beyond anything they would have gotten in any one of those school districts.”

Joseph South, chief learning officer for the International Society for Technology in Education (Photo provided by South)

Working toward equity in the classroom has never been more necessary because of students’ vastly differing experiences during the pandemic. South knows one second-grade teacher who has five kids in her class now who don’t know how to read or even sound out words, after kindergarten and first grade were upended for them over the past two years.

“That’s a big change that will be with us for a long time,” South says — and it’s another area where technology can make a difference, by helping students feel safe and included.

Fear, doubt and anxiety are generated from circumstances where people feel like outsiders, South says, undermining students’ ability to learn. The right technology and tools can help adapt resources to fit kids’ circumstances.

Amanda Young, Graham’s mother, has seen firsthand how technology can address inequity on numerous levels. She runs the Education Imagine Academy, a virtual public school in Wichita with about 500 kids. Many can’t attend class in-person due to homelessness, mental health needs or cancer treatments and the like that leave them homebound and needing flexibility in their schedule for medical care. Others enrolled more recently because of uncertainty around the pandemic.

One thing she’s noticed is how Teams classes can destigmatize the learning experience and make it more inclusive. In a traditional classroom setting, students with needs like her son’s are taken to a different room when it’s time for a quiz, for example, to get individualized attention. But with Teams, other students don’t know who’s in which breakout room, so learning becomes more normalized for different styles and needs.

As educators increasingly harness technology to make learning more equitable, they’re welcoming kids like Graham into what Young calls “a whole new world” that offers greater independence.

Graham Young near the Keeper of the Plains sculpture in Wichita, Kansas (Photo by Travis Heying)

“I used to tell a friend what I wanted to say, and they wrote it down,” Graham says, adding that he’d reciprocate by helping out with science and math homework — his strong subjects. “But now I can get my assignments done on my own. It lets me put my own words into something, rather than having someone else do it.”

Technological advances over the past couple of years have given Graham, who now wants to follow in his grandfather’s and great-grandfather’s footsteps and become a doctor, “the opportunity to see what his future might be like,” Young says.

“If we can give that to every kid, we’re empowering them to be game changers,” Smokorowski says. “That’s why we get into education. And if technology is a way to do it, which I know it is, and we’re using it for them to find their voices, to understand different perspectives and ask the questions, then they can create the change.”

Top photo: Amanda Young and her 11-year-old son, Graham (Photo by Travis Heying)