As datacenters grow, Microsoft’s innovative approach invests in more clean energy to power them

As demand increases for its cloud services around the world, Microsoft is breaking new ground with innovative solutions: It’s collaborating with utilities to increase the amount of clean energy it uses to run its datacenters — and in one recent deal, is even using its own generators to help the local power company bring energy to nearby residents and businesses when it’s needed most.

In the often-complicated world of energy markets, insurance and regulations, these kinds of collaborations with utilities are a straightforward win-win: Making not only datacenters, but also the energy grid, greener. Public cloud datacenters like the one in Cheyenne, Wyoming, are no longer just consuming energy but producing it, embracing a new role as “prosumers.”

The path to greener datacenters begins with using more clean energy to power them. Across the tech sector, it is predicted that datacenters will rank among the largest users of electrical power on the planet by the middle of the next decade.

Microsoft has been steadily working to increase the amount of clean energy used to power its datacenters. Currently, about 44 percent of that power is generated by wind, solar and hydropower sources. In May, Brad Smith, Microsoft president and chief legal officer, outlined the company’s ambition and set a target of 50 percent by 2018 and 60 percent early in the next decade, with the ultimate goal of achieving 100 percent in future years.

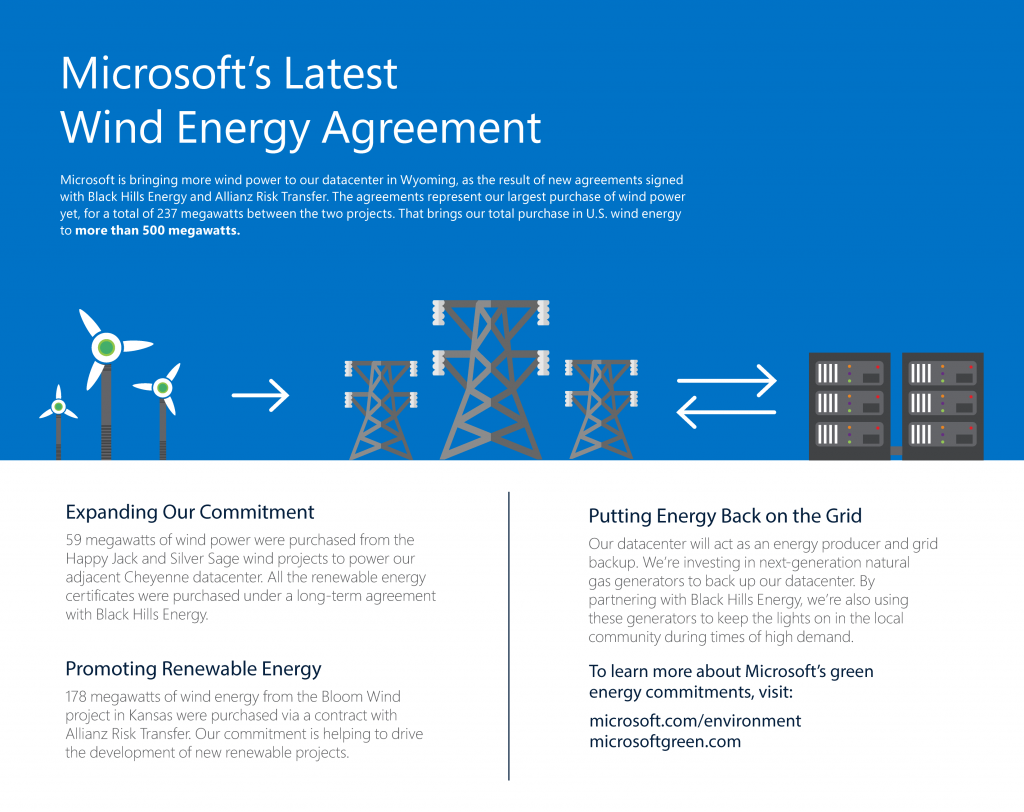

The recent deal — two agreements signed by Microsoft — will make substantial progress towards meeting its 50 percent goal.

Microsoft will reach that goal with the help of two sources, the 59-megawatt Happy Jack and Silver Sage wind farms in Wyoming and a 178-megawatt wind project in neighboring Kansas.

In addition to these purchases, Microsoft is participating in a new tariff agreement with Black Hills Energy, which gives the utility the ability to draw from the datacenter’s normally dormant backup generators. They will be running on natural gas instead of diesel, reducing the need for the utility company to build a new power plant.

“One of the things that makes our relationship with Microsoft extraordinary is our partnership and ability to collaborate with them so we can facilitate the strong growth profile Microsoft has requested,” says Shirley Welte, vice president of operations for Wyoming at Black Hills Energy, which counts Microsoft as a significant partner in Cheyenne. “I think it’s a creative model for the industry, and it sets this relationship apart from what other utilities or energy providers have with datacenters. It’s been a privilege to work with Microsoft. Our collaboration has helped strengthen our business and provide opportunities that are available to Microsoft and others.”

This type of collaboration may be increasingly necessary, as corporate demand for renewable energy continues to surge. According to the Business Renewables Center at the Rocky Mountain Institute, corporations have become the majority purchasers of new wind power. Partnering with utilities like this establishes a two-way exchange of energy. Customer-sited assets become optimized for what the grid needs, tapping into distributed generation as a resource for planning instead of as an afterthought. They become part of utilities’ resources for greater integration of renewable energy.

“In order to solve energy challenges, in terms of supply and management, and carbon, the approach we’re taking is to go after obvious and non-obvious opportunities,” says Rob Bernard, Microsoft’s chief environmental strategist. “An obvious approach might be to contract for green power through traditional PPAs (power purchase agreements). A less obvious approach to reduce stress on the grid and infrastructure is to reduce the energy load we put on the grid by using our own power generation resources, and use data to drive efficiency and optimization. Our goal is to take an approach that works not only for us but also can serve as a model for other companies.”

Christian Belady, Microsoft general manager of cloud infrastructure, strategy and architecture, has long recognized that the scale of the cloud cannot be supported by traditional datacenter design, and also that innovation doesn’t end at the four walls of the datacenter and must expand to the entire surrounding ecosystem.

“We knew that we had an opportunity in Cheyenne to completely re-think the relationship between the utility and customer,” Belady says. “My challenge to the team was to blur the lines between customer and utility so that we move from a traditional supply relationship to something far more efficient and transformative.”

Brian Janous, director of energy strategy at Microsoft, worked with his team to consider each component from the design of the power generation to the regulations and policies that would be necessary to support an entirely new model.

“The utility told us they weren’t going to have enough power generation to support our growth plan, since the datacenter we had in Cheyenne is now much larger than originally planned,” Janous says. “They proposed building a new power plant. But I told them, we’re effectively building power plants behind our meter, in the form of our backup generation, which we need to support our mission critical operations. Why build two plants when you could build one?”

“Why build two plants when you could build one?”

The conversations then led to another innovation – using natural gas to power generators instead of diesel. Diesel is the primary fuel source for generators in the datacenter environment because they provide high power capacity and output. Shifting to natural gas generators makes sense because natural gas is cleaner, less expensive than other non-renewable fuels and considerably more efficient — all important factors in a scenario where they are being used more often by a utility. But the idea needed to be tested.

Janous explains, “The traditional diesel generators we use wouldn’t have sufficed for this use. So we worked to demonstrate that newer natural gas units could meet the specs required to serve as both backup and peaking capacity for the utility, if needed. In not building a new power plant, it’s good for us and other rate payers in the region, who won’t be saddled with extra costs associated with a new plant.”

The datacenter expansion in Wyoming, he says, is “hyper-optimized for flexibility and a very fast start response, which enables our next phase, introducing more renewables into the region. The challenge of renewables is that they’re intermittent in nature. You need to have some combination of controllable load, storage or generation that can respond to the intermittency when the wind isn’t available.”

In this envisioning of the datacenter, these generators aren’t just idle assets, but resources that the grid can tap when it needs to. He says this behind-the-meter generation is a “huge step that really changes the dynamic between the customer and utility in a new and progressive way. You continue to have large-scale generation, but now you also must consider the integrations of electric vehicles, rooftop solar, small scale power generation — all down at the customer level. It’s a major shift in how the electricity grid operates.”

Chris Kilpatrick, director of rates and resource planning for Black Hills Energy, worked with Janous for nearly three years in coming up with solutions for Microsoft’s energy needs in Cheyenne.

“From a renewable perspective, this is another in the line of creative solutions that we’ve worked on with Microsoft. They are very energy savvy. They understand the energy market and are willing to look outside of the box to try to find solutions, even before the datacenter was built,” says Chris Kilpatrick. “The best example is this new tariff that is applicable for customers as long as they meet certain criteria. It’s a unique solution that leverages generation for those customers and allows them the opportunity to buy renewable energy on the market, if that’s what they choose to do.”

In regulated markets like Wyoming, companies buying power have to go through public utilities commissions that set tariff structure. This means that any new structure needs to have the buy-in from a broad coalition of customers in order to be successful. In this case, the Public Service Commission of Wyoming determined in its order that this new tariff “eliminates rate impacts and other risks for customers that are associated with the addition of large new loads while also providing additional economic development opportunities in Cheyenne.”

“When you build a renewable power plant, the utility has to build up backup capacity to meet reliability requirements,” says Michelle Patron, director for sustainability for Microsoft, who manages activities related to public policy on energy and environment and sustainability. “By coming up with this new innovative arrangement, the utility no longer has to invest in a power plant because they can use our backup power.”

“The intent is to mitigate Microsoft’s need to use the backup generation, while ensuring valuable capacity on the ground so Microsoft can continue its datacenter operations, which is very critical to their needs,” Kilpatrick says. “It also allows the other customers of Black Hills Energy the use of Cheyenne’s utility generating assets, independent of each other.”

Microsoft’s willingness and openness to look at options that don’t fall under traditional utility thinking made all the difference, Kilpatrick says. Not being afraid to try something new has been very helpful.

Patron says these kinds of “proof of concept” solutions help shape public policy moving forward, which in regulated electricity markets are made of tariff arrangements at the state level. This model could bring more renewable energy online.

“For the first time, we have a holistic solution to maintain reliability on the grid and at the same time, create an environment to allow for more intermittent renewable energy,” says Janous. “It’s really solving both sides of the equation at one time. The traditional mindset in the industry is that we build datacenters with backup generation. The result is a less-than-optimal solution for both the datacenter and the grid. At Microsoft, we recognize that we’re building power plants that happen to have datacenters next to them. And that changes everything.”

Find out more at Microsoft on the Issues.

Lead image: Microsoft’s datacenter in Cheyenne, Wyoming.