A lost boy and a father’s search: how Microsoft technology helped solve a four-year mystery

On a hot morning in June 2012, Junxiu Wang and his son awoke in the city of Guangzhou, northwest of Hong Kong, and started their day.

Wang was working a short-term job in Guangzhou and had taken his 14-year-old son, Yesong, with him. The pair ate breakfast, then Wang went to use the bathroom. When he came out, Yesong was gone. The father was immediately worried. Yesong, his middle child, had Down syndrome and was unable to speak.

Wang called the boy’s aunt, thinking he might have gone to visit her, but he wasn’t there. Growing increasingly anxious, he went to a nearby subway station and asked if anyone had seen his son. A vendor and a security guard reported seeing a boy who looked like Yesong carrying a bag. Wang’s fears intensified. If his son ventured very far away, he knew, he would not be able to find his way back.

It would be almost four agonizing years until Wang found out what happened to his son. The answer would involve an exhaustive search, a dedicated nonprofit director, a popular Chinese reality show, Microsoft facial recognition technology and a father who never gave up hope.

And their story was just the beginning. The technology is now helping other families find much-needed answers and has powerful potential for addressing an issue that has long plagued China. There are 64,000 cases on the website of Baobei Huijia (Baby Come Home), a leading nonprofit organization launched in 2007 that is dedicated to finding missing children.

In 2015, Eric Zhou was thinking about how technology might be used to more effectively combat human trafficking. Zhou is a Shanghai-based senior business intelligence manager for the Digital Crimes Unit in Microsoft’s Corporate, External & Legal Affairs group in China, which uses data analytics to fight cybercrime and protect vulnerable populations, including children. He came up with a project for Microsoft’s annual worldwide employee Hackathon, enlisting his friend Kevin Liu from the Microsoft Support Engineering Group to develop an application that could help find China’s missing children.

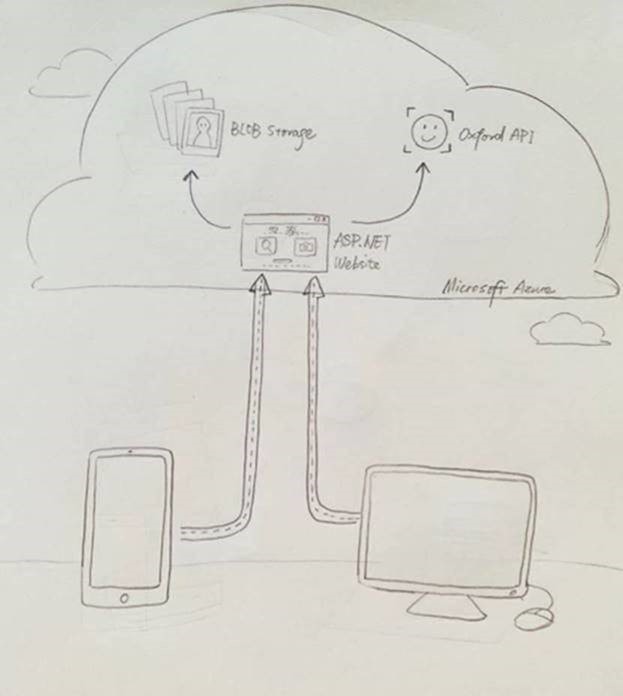

The effort resulted in the creation of Photo Missing Children, or PhotoMC, an application designed to help find missing children through Microsoft’s face recognition application program interface (API). The Microsoft Face API is a cloud-based service that uses advanced algorithms to scan images of faces for identifying features and determines the likelihood that two faces belong to the same person. It can scan a database of thousands of faces and return a list of possible matches within seconds. The API analyzes 27 different facial characteristics and can identify a person across multiple photos, even at different angles and with varying facial expressions.

The technology is part of Microsoft Cognitive Services, a collection of tools that allow developers to add features such as emotion detection, vision and speech recognition and language understanding to applications across devices and platforms.

Zhou approached Crossing Wang, Microsoft China Philanthropies lead, to connect him with an organization that could put PhotoMC to use.

“When Eric brought this idea to us, we thought it was a good opportunity to support his project and apply it in the real world,” she says. “We wanted to do something to help families.”

Crossing Wang’s team reached out to Baby Come Home, which runs a website that allows people to upload photos in various categories — parents can upload photos of their missing children, and others can upload photos they take of children they come across who might be missing or abducted.

The Microsoft team offered to make PhotoMC available to Baby Come Home, but the organization’s founder, Baoyan Zhang, was initially skeptical. Other companies had made similar offers, she says, but they typically didn’t follow through or seemed primarily interested in seeking publicity. Or the companies would realize after a few conversations that their technology could not address a primary challenge of locating missing children — cross-age facial recognition.

“Those children may have gone missing at the age of 3 or 4, but they maybe are 20- or 30-something when we look for them,” Zhang says. “So after a few contacts, we felt it was a waste of time, and we declined some other cooperation requests after that.”

But Zhang believed facial recognition technology offered the most promise for finding missing children, and she figured if any company could come up with an effective tool, it was Microsoft. Also, her organization needed help. Baby Come Home has found more than 1,900 missing children in the past few years, but the work has been time-intensive and difficult.

The organization’s dozen employees were overwhelmed with the task of manually sorting through thousands of images of missing children on a government website and trying to find matches for the 60,000-plus photos of missing children and adults in Baby Come Home’s databases.

Unless children have distinguishing features, like unusual teeth or distinctively curved eyebrows, changes in appearance over time can make it hard to recognize them. And after looking at images for too long, fatigue sets in and accuracy drops. Facial recognition technology offered new promise by reducing human error and making the search process almost instantaneous.

The Microsoft team first met with Zhang in August 2015, and based on feedback from the organization, spent about a month modifying and customizing PhotoMC to make it more effective. The changes included creating the ability to separate information about parents looking for their children and children looking for their parents into discrete databases that then could be compared for possible matches, and the capacity to import more photos.

In December 2015, after additional changes to improve performance and several training sessions, Baby Come Home started using the new tool. Then, when an at-risk child was spotted, a photo of the child could be uploaded to the organization’s website and PhotoMC would search for matches. Zhang was hopeful.

“(I thought that) facial recognition technology would definitely be a great help to us, if it worked out this time,” she says.

In the days after Yesong disappeared, Junxiu Wang searched at subway stations and youth shelters in the area. He walked the streets of Guangzhou, desperately hoping to find his son. But in a city of more than 14 million, the chances of spotting him were almost nonexistent.

The anguished father put notices in newspapers and on television. He contacted China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs in Beijing and asked for help. Weeks and months stretched by with no leads, but Wang clung to the belief that his son was still alive. And as long as Yesong was alive, Wang would not stop looking for his boy.

Yesong had been missing about three years when Wang found Baby Come Home’s website and decided to go visit Zhang to ask for her help. In July 2015, he took a train from Guangzhou to Tonghua City in northeast China, almost 1,900 miles away. Wang arrived at the organization’s office exhausted and soaked, carrying a large jackfruit and a box of taro as gifts. After he left, Zhang opened the jackfruit and discovered it was rotten. She wondered how long the father had traveled to get there.

“It made our hearts ache to see him like that,” she says, recalling how employees’ eyes would fill with tears at the thought of Wang.

Six months after Wang’s visit, in January 2016, China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs launched a new website to publish information about children living in shelters across the country. Baby Come Home ran the photo of Yesong that his father provided against 13,000 images on the government site, and within seconds, PhotoMC came up with a list of 20 possible matches. One was a boy living in a government-run shelter in the Panyu district of Guangdong City, about 24 miles from where Yesong went missing. Zhang wondered, could the boy be Yesong?

The father looked at the matching photos and immediately identified his son. He provided a DNA sample, which was matched against a sample from the boy at the shelter. Arrangements were made to bring Wang and the boy together on the popular Chinese television show “Waiting for Me.” The show, which runs on China’s predominant state broadcaster, China Central Television (CCTV), aims to help people find missing children or other loved ones and is produced in partnership with Baby Come Home. The audience and the relative wait in suspense for the opening of a large set of doors, behind which is either the missing person or a police officer who discusses the unsuccessful search.

In February 2016, Wang sat in a chair on the show’s stage, his hands clasped nervously in his lap. The doors opened slowly to reveal Yesong, who by that time was 17. Wang exhaled audibly and crossed the stage, crying as he clasped his son to him. At first, Yesong didn’t recognize his father, Wang says. But within a month, he says, Yesong readjusted to being home with his parents and two siblings and is now doing well.

Crossing Wang, who is not related to the family, recently visited them and says Yesong’s parents told her that he was withdrawn while he was at the shelter but has become more outgoing since returning home and enjoys helping people. He goes to a local supermarket every day to help out, she says, gathering shopping carts and working with employees to organize items.

“His neighbors and the staff at the supermarket like him very much,” Crossing Wang says. “If he was still in the shelter, his life would be totally different.”

Yesong was the first missing child found with the help of PhotoMC, but the application has since helped find four other missing boys in China and several other possible matches are being followed up on and verified.

One of the boys, a developmentally disabled 17-year-old, was lost in April 2015 in Beijing and had been living in a shelter. Baby Come Home found him with PhotoMC, and on April 28 he went home with his parents.

Another 17-year-old, also with limited ability to communicate, went missing in January 2014 in Guangzhou. His parents recently registered his information on Baby Come Home’s website, and PhotoMC quickly found a match with a boy who had been taken in by a shelter two years ago. The relieved parents visited the teen in the shelter at the end of April and were expecting to take him home as soon as DNA results were verified.

The third boy, a 16-year-old who has a mild intellectual disability, went missing while playing outdoors in Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province. On May 8, Baby Come Home used PhotoMC to find a match with a boy living in a shelter 60 miles away. It was the missing teen, whose parents picked him up the following day and took him home.

And another boy, who has autism, was found May 18 in a shelter 30 miles from his grandparents’ home in Fuzhou after running away more than three years earlier. His grandfather went to the shelter and confirmed the boy is his grandson.

Microsoft is continuing to work with Baby Come Home to refine PhotoMC, which was developed in collaboration with Microsoft Research Asia and the Microsoft Cloud & Enterprise China group. Seeing Yesong reunited with his father was a touching moment for everyone involved, Zhou says, and the team hopes the application can help bring answers to many more families.

“We feel very good that our technology can help,” Zhou says. “We are proud that we helped these families be reunited.”

Images of the Wang family by Zhang Kelei.