Microsoft VP’s diagnosis fuels employees’ heartfelt efforts to help others

Matt Lydon would find excuses not to get up and write on the whiteboard at meetings. When the Microsoft exec had to speak publicly, as he often did, he’d try to make sure he was sitting on his right hand or had it jammed tightly in a pocket so no one would notice the tremors.

For almost three years, he told few people his secret and lived with the fear of what it would do to his career, his friendships, his whole life. But hiding it was exhausting and couldn’t continue forever.

So one morning in late August, Lydon, the vice president of Worldwide Search Advertising, told hundreds of colleagues attending an all-hands meeting in Redmond, Washington, and connected by Skype from Microsoft offices around the world that he has Parkinson’s disease.

The room fell silent. Stunned eyes filled with tears. Yet even amid the initial shock, recalls Search Advertising Business Director Sarah McGovern, “The first thing everybody said is, ‘How can I help? What can I do?’”

That unexpected upside of Lydon’s diagnosis has only gained momentum since: Many people on Lydon’s team and beyond have joined him in broad efforts to help others who have Parkinson’s, pouring their time, money and technical expertise into the cause.

Their dedication has already had a powerful effect on the Northwest Parkinson’s Foundation, a nonprofit that helps improve the quality of life of people living with the disease, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation, which is focused on finding a cure.

“We can better serve people with Parkinson’s right now because of Microsoft and what Matt has done. This will directly impact thousands of lives across the region,” says Northwest Parkinson’s Foundation Executive Director Steve Wright. “Anything we want to do right now is possible.”

Lydon began helping the nonprofits about a year before announcing his diagnosis. He wanted to give back because he’d leaned heavily on Northwest Parkinson’s Foundation in his darkest time — the first year after receiving the news — but he says it was also “a selfish reaction” to the way it made him feel.

“Every year from now on is going to be tougher,” he says. “When I got involved, I stopped focusing on the symptoms and the outcomes. I felt more energy, and I am healthier as a result.”

This will directly impact thousands of lives … Anything we want to do right now is possible.

The second thing that “flipped a switch” on his outlook came a few weeks ago. He’d just gotten back from a trip to Hawaii — a perk of winning the Microsoft’s Founders Award for outstanding leadership —and McGovern had scheduled a meeting. Lydon was bewildered about the purpose of it, but he went.

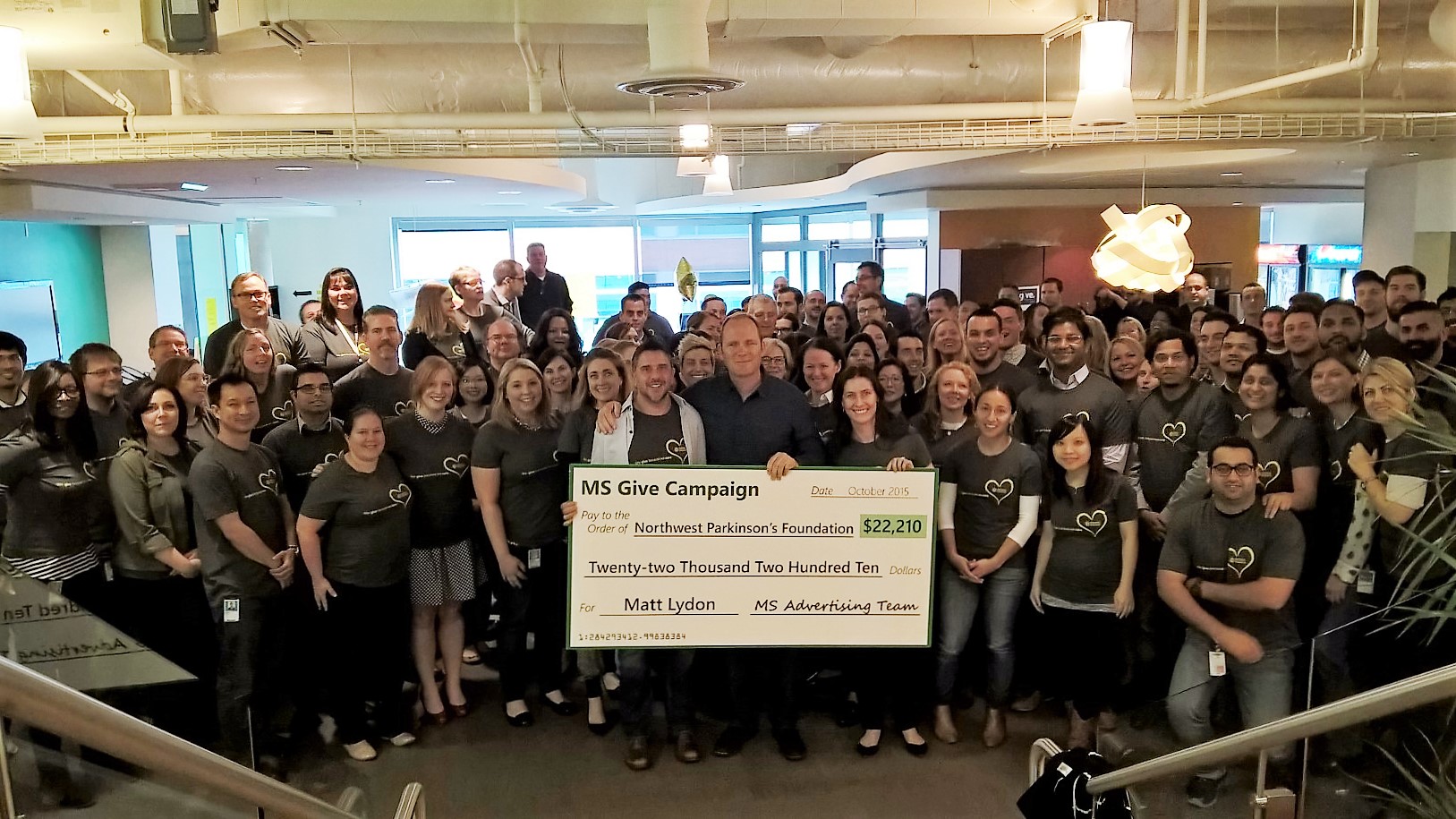

He was surprised to find a crowd of employees holding a gigantic check for Northwest Parkinson’s Foundation. They’d quietly held a fundraiser while he was gone, selling T-shirts for a minimum $25 donation, though many people shelled out far more.

Microsoft matched each donation. The generosity topped $22,000.

“I totally broke down. It was crazy,” says Lydon, who recently accepted a spot on the Northwest Parkinson’s Foundation board. “The support has been amazing. The number of people who have wanted to get involved speaks to the character of the Microsoft community as a whole, and the thing that has helped me day-to-day living with this disease is having that support.”

The Bing Ads Marketing Team raised another $8,000 through a 5K run. Still another fundraiser on Microsoft’s Redmond campus had employees getting their pictures taken in a DeLorean like the one that Michael J. Fox’s character in the movie “Back to the Future” used to travel through time.

That event raised almost $9,000 for the foundation co-founded by the popular actor, who revealed he had Parkinson’s in 1998.

Across the world, employees who work on Lydon’s teams in Australia and Singapore have joined efforts to raise money for their local foundations.

Lydon had an early sign of the disease long before he realized what it meant. He noticed a stiffness in his right shoulder. His doctor figured it was a remnant of younger days playing football and rugby, and prescribed physical therapy that didn’t really seem to help.

Three years later, at a regular checkup, Lydon told his doctor he’d started losing coordination in his right hand. It slowed his typing and forced him to take frequent breaks from the keyboard.

The doctor whisked him upstairs to see a neurologist, who had Lydon walk down the hallway, then touch each fingertip to his thumb in succession. Lydon thought maybe a pinched nerve was the reason he struggled to get his fingers to cooperate.

“We went into his office, and he looked at me and said, ‘I’m sorry to tell you, but you have Parkinson’s,’” Lydon recalls. “It just hit like a ton of bricks.”

The doctor could tell by the way Lydon’s right arm didn’t swing when he walked, but he also recognized the disease as soon as they first spoke. Lydon’s face lacked virtually any trace of emotion, a symptom involving the motor impairment of facial muscles that’s sometimes called “the mask of Parkinson’s.”

I just cried and thought, ‘Life is over. How am I going to support the kids? How long can I work?

Lydon listened as the doctor explained some of the details — that it was a progressive disorder of the nervous system with no cure — and then asked him to leave the room. Alone, he fell apart.

“I just cried and thought, ‘Life is over. How am I going to support the kids? How long can I work? I’m going to end up in a wheelchair, unable to take care of myself,’” he recalls. “You immediately go to the end of Parkinson’s, not the journey between now and then.”

He told his wife that day, but he wouldn’t feel strong enough to tell his three kids without being “a basket case” for nearly two years — and he didn’t want anyone to know until they did.

So in secret, he tried to learn all he could; a Bing search led him to Northwest Parkinson’s Foundation. “I called them up and said, ‘Help,’” he recalls. “And they started helping.”

The organization connected him with a specialist, gave him advice on managing his condition and helped him begin to move forward. It put him in touch with other people who also have young-onset Parkinson’s — diagnosed before age 50 — including other execs at well-known companies.

Medication has since helped with some of the symptoms, including the tremors and limited facial expressions.

Lydon began exploring what he could do to help the nonprofits about a year ago. He sat down with Wright and learned that Northwest Parkinson’s Foundation had major problems with its technology infrastructure. Wright says Lydon got him help “within the hour.”

Lydon connected the foundation with Microsoft’s Tech Talent for Good program, which meant five or six Microsoft employees would solve the tech problems for free — and Microsoft would match their volunteer hours with a cash donation, which struck Wright as almost “too good to be true.”

Lydon and Wright continued to meet regularly, discussing ways to improve the foundation’s website, raise money and reach other big goals — all efforts that are being strengthened by the many employees Lydon has inspired to join the effort.

“The people who work for him love him,” Wright says. “They really want to do something nice. They want to help. You don’t see that all the time.”

Lydon and Wright recently began working with a team of college students from Greece who won the Ability Award in Microsoft’s 2015 Imagine Cup competition. Team Prognosis created an app aimed at detecting Parkinson’s disease early based on voice characteristics.

The team had been working to improve their algorithms but didn’t have a way to capture enough voice samples of people who have the disease. Northwest Parkinson’s Foundation’s reach will help them collect thousands, Lydon says, which breaks down a major hurdle for the grateful students.

Among his colleagues, Lydon’s courage to share his diagnosis so broadly and the emotion that crept into his voice that day were “a call to action for a lot of us to just get involved,” says Kim Farmer, a search sales manager. “It made Parkinson’s personal.”

She met with Wright just two days after Lydon’s disclosure to ask what she could do.

Farmer and about eight colleagues helped the foundation with its annual auction Oct. 24. Lydon didn’t even know until he showed up at the event and spotted them working away on a Saturday. At the end of the evening, the volunteers were already discussing how they could improve their efforts to run the silent auction portion of the event next year.

“Everybody was bought in to coming back, and putting together systems and processes so that we could be more efficient — which is totally the Microsoft way to do things,” Farmer says.

Lynne Kjolso, general manager of Search Sales in the Americas, and other Microsoft employees gave up a Saturday to volunteer at the foundation’s tenth annual HOPE Conference, escorting attendees from the parking garage and assisting people with mobility challenges.

“Matt’s story is super inspiring. It’s a very difficult disease, and he’s made it very, very real for all of us in terms of what the day-to-day struggles are, and what the long-term prognosis and hopes are,” Kjolso says. “The reason I volunteer, and the reason I give, is to honor Matt and help build some momentum behind the cause.”

He really encourages people to find out what they’re passionate about and supports them … I think people just want to reciprocate that.

Still other Microsoft employees have joined Lydon’s work with the Michael J. Fox Foundation. Four will analyze the organization’s code and server setup to help boost its website’s speed and stability; Lydon also brought in someone from Bing who will help the foundation get more web traffic.

“Getting this kind of in-kind consulting service and access to expertise can really have a big impact for us, given that technology isn’t our core business,” Deborah W. Brooks, who co-founded the nonprofit with Michael J. Fox. “He really was enthusiastic about finding a smart place to start.”

Brooks is excited about the “great promise” of projects that are just getting started. She came to Seattle to meet with Lydon in July, roughly a month before he made his diagnosis widely known, and was struck by his passion and commitment.

“Getting a diagnosis like Parkinson’s is obviously, in many ways, a life changing event. Not everybody feels immediately comfortable or is in the position to take actions in such a public and impactful way,” Brooks says. “His making that choice is already important and special.”

McGovern says it’s no surprise that so many people at Microsoft have rallied around Lydon and his commitment to make a difference. She thinks it stems from his strengths as a manager, from the trust he puts in his team to his humor that often lightens tense moments.

“He really encourages people to find out what they’re passionate about and supports them. That’s one of the things that really sets him apart as a leader,” McGovern says. “I think people just want to reciprocate that.”

Portrait photography by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures