One year later, hackathon project and MSR Enable team push limits on technology that empowers

It began as an overhauled wheelchair fitted with electronic gadgets, hastily cut Styrofoam and a fair amount of duct tape, but the enormous promise of the hackathon prototype was unmistakable.

Just one year later, the technology gives former pro-football player Steve Gleason, who lost the ability to move his limbs to ALS, the capability to do what he couldn’t before: Cruise around the park or happily set “land-speed records” with his 4-year-old son, Rivers, cuddled on his lap, because he’s now able to propel himself without someone else’s help.

The Eye Gaze Wheelchair that captured imaginations and the grand prize at Microsoft’s first company-wide //oneweek hackathon last summer has made major advances, all from the dedicated efforts of a team that was created to work on such empowering projects at Microsoft full-time.

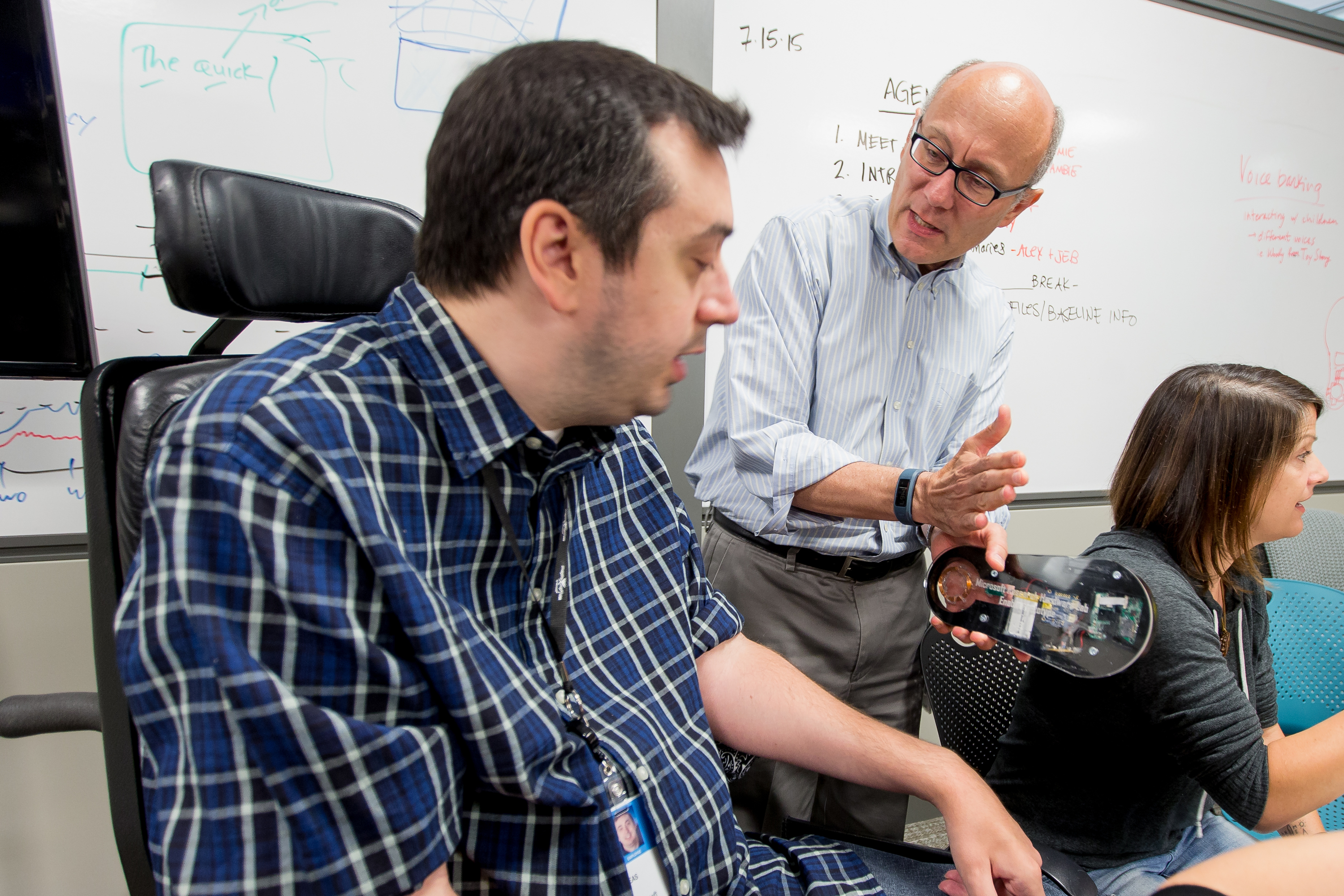

“Hackathon prototypes are fragile. They kind of work, they kind of don’t work, and that’s fine, because they show what might be possible,” says Microsoft Research Chief Scientist Rico Malvar. “We have a lot of work ahead of us, but our hope is that this technology will eventually be available to people with disabilities and make a big difference in the quality of their lives.”

As hackathon teams work on thousands of new projects for the second year, the Microsoft Research (MSR) Enable team’s progress on the Eye Gaze Wheelchair helps demonstrate how innovation can overcome limitations, and it’s a powerful example of Microsoft’s aim to help everyone on the planet achieve more.

“It’s showing what the potential is for Microsoft to really, truly empower people with technology,” says Jenny Lay-Flurrie, chair of the disAbility Employee Resource Group. “Everyone is deriving a lot of meaning from this. It matters.”

But perhaps no one is more excited at how far the Eye Gaze Wheelchair has come than the man who inspired its creation in the first place. Gleason, 38, says the device has liberated him and “absolutely revolutionized” his life.

“I was at a point in my disease progression where I could no longer drive myself. Stuck,” he explains. “I am no longer confined to my wheelchair; I am set free by my wheelchair. I am eager to get this to market so we can share it with other people who can utilize it.”

Gleason says the MSR Enable team’s efforts have “filled a critical void” in innovative technology, which he says can be a salvation for someone with severe physical limitations.

“Without technology, I would have been forced to quietly fade away and die,” Gleason says. “Despite how helpful technology has been for people like me, there is more we can do. Much more. And Microsoft has simply stepped up to become an innovative leader in the marketplace.”

Gleason is perhaps best known for a stunning blocked punt in the New Orleans Saints’ first game in the Superdome after Hurricane Katrina, but he and the Team Gleason foundation scored a major victory recently with the Steve Gleason Act, passed by the US House of Representatives earlier this month to require Medicare to cover speech-generating devices for many people who need them.

Gleason, who will be speaking at this week’s //oneweek event, has helped shape the MSR Enable team’s work on the Eye Gaze Wheelchair, and he often sends team members videos of himself using it. In one, he brings Rivers to his old stomping grounds, the Saints’ training facility, and demonstrates his agility at driving down the field.

In another, he sports a playful grin as he announces, “I am about to set the land-speed record for eye driving.” A sensor tracking his eye movements, Gleason uses the wheelchair to carve a curved path around some makeshift obstacles.

Principal Development Lead Jay Beavers and more than a dozen others on the MSR Enable team have turned the hackathon creation into a stable device Gleason is able to use regularly on his own in his hometown of New Orleans. He gives feedback for improvements, and over the past year, there have been many.

“We’ve rewritten everything,” Beavers says. “It has a new user interface, and the control system is much better.”

The team has had the interface box that Beavers once soldered by hand professionally fabricated. Rapidly evolving technology and long-standing collaboration with Tobii Dynavox means the sensor – the camera that tracks eye movements, letting someone use a Surface tablet’s onscreen controls by simply looking at them – has been replaced as part of the research with a developer model with more precision at a substantially lower cost.

The team has enlarged the user-interface controls so that people can more easily operate them with their eyes. They’ve also added buttons to allow users to “stride right” and “stride left,” which helps them make more gradual turns, as well as reverse.

Microsoft summer intern Jeb Pavleas, who suffered a spinal cord injury 15 years ago and uses a wheelchair himself, is working on a four-camera system that will help people using the wheelchair see potential obstacles, navigate doorways and otherwise get around more easily even if they’re unable to move their head.

Pavleas says he often comes up with technology- or hardware-related ways to make things easier for himself at home, so he’s glad to work with a team that has the passion and know-how to work on improving accessibility more broadly.

“It’s all about trying to improve the quality of life for people with disabilities, as well as make tasks more efficient,” Pavleas says. “I’ve found that in my own life, I can usually do stuff that other people can do, but it often just takes more time. Technology is a big help with that.”

Beavers says his team is working on various safety features for the Eye Gaze Wheelchair and has made many of the recent improvements after having people use the chair and share their ideas. He believes that level of feedback is key.

“It’s the first time in my career at Microsoft I’ve had the opportunity to sit down with users, face-to-face, on a very frequent basis and say, ‘What do you need? How should we do this differently?’” he says. “That makes a huge world of difference.”

Malvar says the project highlights a newer “hacking spirit at Microsoft of trying things more, thinking more about larger impact to users first, and potential business positioning later.” It means building, testing, trying new things and trying again.

“Every idea is reasonable until proven otherwise,” Malvar says. “We really have to have our minds open to new ways of using the technology.”

The team is also working on improvements to its Eye Gaze speech generator, which tracks a user’s eye movements as he or she looks at specific letter keys on an on-screen keyboard and reads words aloud – another technology Gleason uses. They are working to make it faster and sound less like a computerized voice and more like the person who is using it for more natural conversations.

Gleason has been the driving force behind the Eye Gaze Wheelchair and the formation of the MSR Enable team. It all began early last year when he shared some goals with the company, including his desire to be able to play with his son, talk more easily with his wife and move his wheelchair himself.

Lay-Flurrie received Gleason’s goals in an email and quickly had a crowd of Microsoft employees who’d never met Gleason or each other volunteering to help. She says an “amazing team” worked to fulfill some of his wishes at last year’s hackathon.

Technology for a wheelchair Gleason could operate himself was, as Lay-Flurrie recalls it, “kind of a pipe dream” at the time. But the hackathon was “one of those environments with crazy ideas where nothing was too off-the-wall,” she says. “If we didn’t have the right expertise, we’d pick up the phone and find someone in the company who could help us.”

So the group, dubbed the Ability Eye Gaze team, rolled up their sleeves and came up with the prize-winning prototype that was the basis for the past year’s advances.

It brought a huge response from people living with ALS and others around the world. Everyone wanted to know one thing, according to Lay-Flurrie: When could they get their hands on the technology?

Lay-Flurrie says the emails she received were touching and beautiful, but the technology was in early stages and not ready for widespread use. Still, Microsoft quickly trained staff on its Disability Answer Desk about the different technologies that could help people living with ALS so that “if people wanted to get technical support, they had a team of experts on hand to help,” she says.

That support team continues to assist customers living with the disease.

The focus now is on the pathway to take the Eye Gaze Wheelchair from the research stage, where it is now, to a product that can help many people. “This is the first project for the MSR Enable Team, and there will be more,” Lay-Flurrie says.

“You’ve got this amazing mix of people who are just bringing their all and are committed to the goal,” she says. “We’re doing it because we want to see Steve and others truly live their lives. If we can make one little thing easier, bring it on.”

Lead photo: The MSR Enable team pictured against the on-screen controls of the Eye Gaze Wheelchair. Front row, left to right: Jenny Lay-Flurrie, Jeb Pavleas, Ann Paradiso, Rico Malvar, Harish Kulkarni. Back row, left to right: Irina Spiridonova, Ben Elliott, Alex Fiannaca, Jay Beavers, Pete Ansell. (Photo by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures)