Students will show inspiring technology to help people overcome challenges in Imagine Cup World Finals

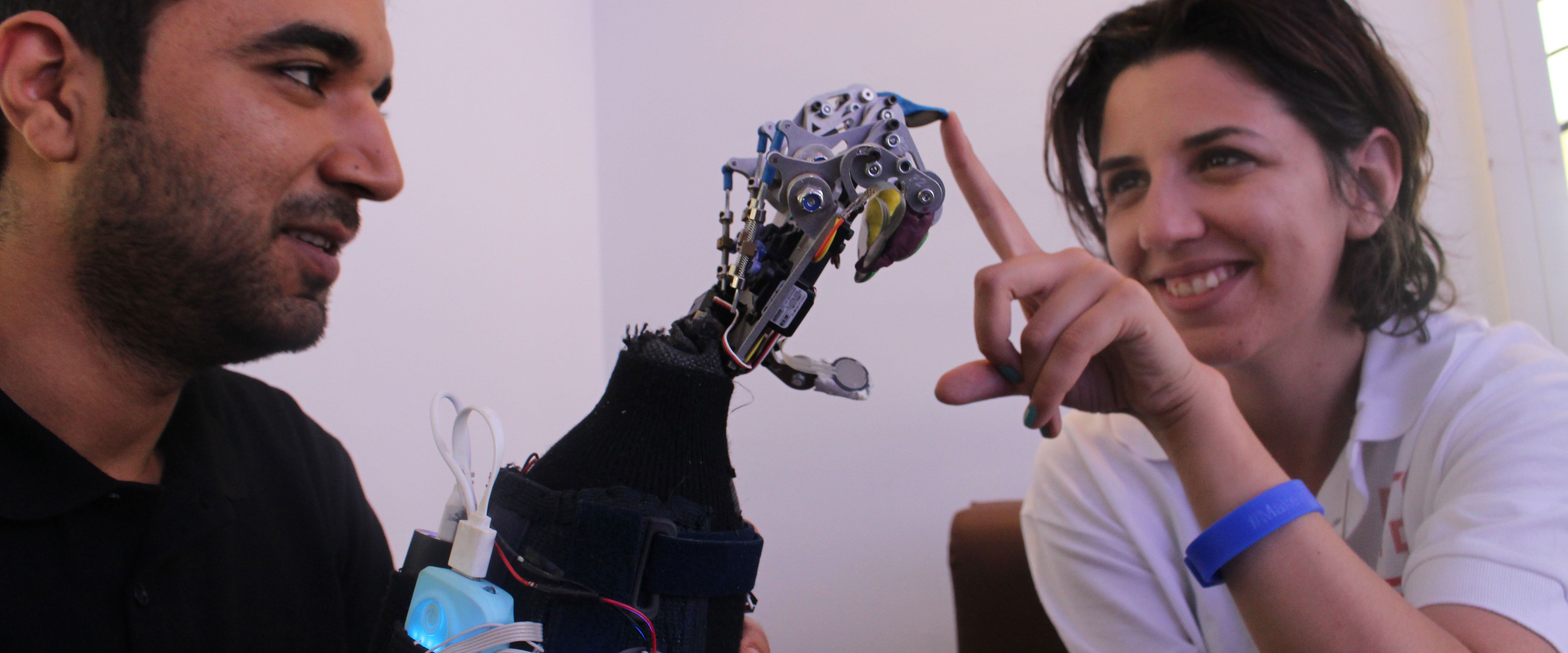

It hasn’t been easy for Mohamed Zied Cherif to keep up with his fellow engineering students. A birth defect that prevented his right hand from fully forming means he can’t hold two things at once, or control a computer keyboard and a mouse at the same time.

As a kid, he tried to use a prosthetic hand but spent months struggling with how uncomfortable it was and finally just threw it away.

So the Tunisian college student and three others put their minds to coming up with something better. This week, they will showcase their Smart Hand, a programmable electronic prosthetic device that doesn’t require surgery, at Microsoft’s 14th annual Imagine Cup student technology competition.

“I can wear it two minutes, or I can wear it for hours, and it does not bother me,” Cherif says. “I don’t think about catching up with my colleagues in class anymore. It makes an impact on my life — and I am certain it will on many people.”

The Smart Hand project is just one way this year’s Imagine Cup world finalists have taken on some of the toughest challenges or heartaches they’ve seen people endure — or have faced themselves — to create inspiring solutions with technology.

Students on 35 teams from around the globe are at Microsoft headquarters in Redmond, Washington, this week to compete for more than $200,000 in cash and prizes, a private mentoring session with Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and the title of Imagine Cup World Champion.

People around the world can watch the Imagine Cup awards ceremony at 9:30 a.m. PT Thursday to see who wins this year’s Games, Innovation and World Citizenship competitions. At 9 a.m. PT Friday, the three first-place winners will face off before a stellar panel of judges in a nail-biting final round that will be streamed live.

“Year in and year out, I’m incredibly impressed by the ingenuity and creativity shown by our Imagine Cup competitors, and this year is no different,” says Steve Guggenheimer, corporate vice president of Developer Experience and Microsoft’s chief evangelist. “From apps for diagnosing disease to compelling virtual reality games to clever wearables, this year’s Imagine Cup teams are pushing the envelope of student innovation.”

Cherif’s team, Night’s Watch — a hat tip to their enthusiasm for “Game of Thrones” — is competing in the World Citizenship category. Smart Hand began as a school assignment: Soumaya Tekaya, Mohamed Assil El Mekki and Amir Ben Said were exploring project ideas and Cherif needed a team. After a conversation that was admittedly “a little bit awkward,” Tekaya recalls, the four agreed to build something to help Cherif.

An electronic prosthetic hand can cost upwards of $100,000, not including the cost of the surgery that’s usually required to make it respond to the user’s muscle movements, Tekaya says. The team wanted to make something less expensive, less complicated and more comfortable.

Rather than using sensors that have to be surgically implanted, the team designed Smart Hand to work with an arm band that detects the wearer’s muscle movements externally, then sends the data to a mobile application that allows the person to customize the movements of the device, Said says.

Users can switch modes depending on their tasks — to scroll up and down on a phone, for example, or grab and release a coffee cup.

Cherif says Smart Hand can help him to do many things, from using a computer to helping his mother cook. He and his team are hoping to refine the device to help as many people as possible.

“We have a mission,” Tekaya says. “We really, really care about our project, and we know that Imagine Cup with help us make it worthwhile.”

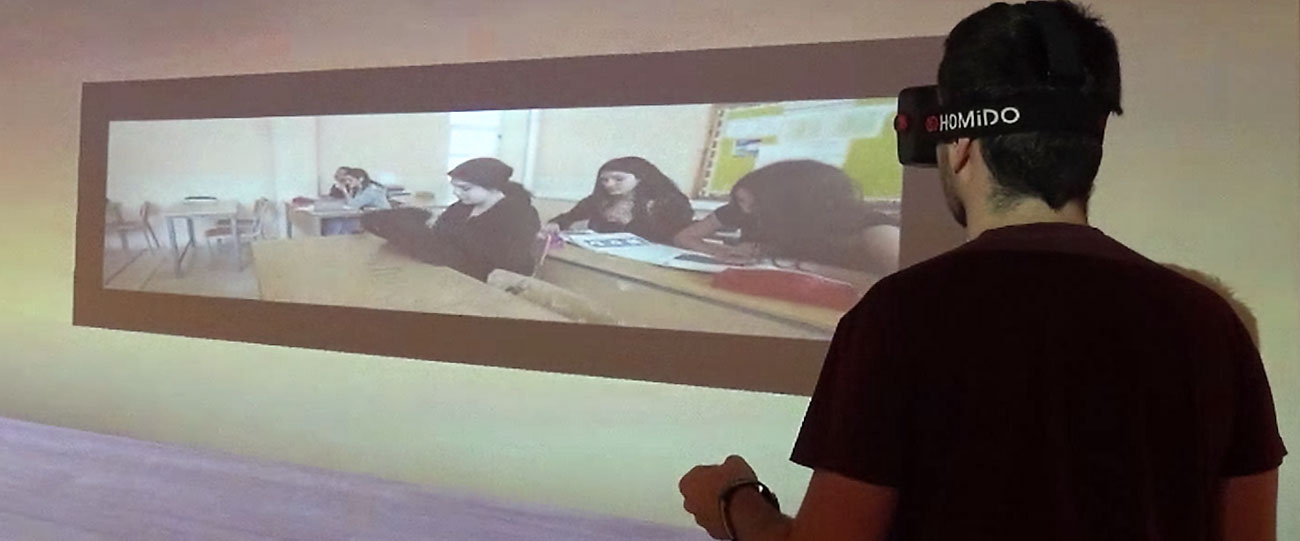

For four students in Greece, it was the distressing issue of bullying that inspired them to act. Their World Citizenship project is named for Amanda Todd, a Canadian teen who made a video detailing her experience being bullied before taking her own life in 2012.

“We watched the video all together, and it was a really moving moment. It was really sad that people across the globe are feeling this way,” says AMANDA team member Vasileios Baltatzis. “People, especially children, usually don’t talk about these things. We wanted to reach them, and technology is the way.”

Baltatzis, along with fellow students Georgios Schinas, Ilias Chrysovergis and Margarita Bintsi, came up with a gamified virtual reality app that’s designed to assess and help build three different traits in the person who uses it: empathy, awareness and self-esteem.

Wearing a virtual reality headset, users find themselves in a 3D space where they encounter interactive scenes, many of them involving people bullying others. The idea is to gauge the user’s response. A Microsoft Band measures heart rate and other biometrics to determine whether the person shows tendencies toward bullying or being a victim.

Subsequent levels of the game work toward building empathy, awareness and self-esteem by putting the user in the shoes of a victim, bully or bystander to decide what to do and see the results of those actions, Chrysovergis says.

They believe AMANDA is better than typical approaches such as lectures and questionnaires to combat bullying. They’ve begun testing it on students and hope to eventually make it available in schools around the world.

“Bullying is an international problem … and there is no actual holistic solution,” Baltatzis says. “Hopefully with this, we can change how the world sees intervention in bullying.”

Three current and former University of Utah students wanted to tackle a much different challenge, but one that also causes problems for many children: Amblyopia, or “lazy eye,” a surprisingly common affliction that often goes undiagnosed.

“If lazy eye isn’t treated when someone is young, it gets much more difficult to treat,” says HealthX team member Dan Blair. “This can cause learning disabilities. It can make it harder to read. It seriously can affect your life, and (many) kids don’t know they have any problems.”

Lazy eye is usually only detected in a full eye exam, which can be tricky for kids who can’t yet read and have difficulty communicating what they see or which glasses are most helpful. It’s also typically treated by placing an eye patch over the child’s “good” eye, which can cause that eye to weaken.

In a game created by Blair and teammates Ahmad Alsaleem and Ahmad Nassri, the player is a cowboy roaming the Wild West in search of treasure chests as large birds swoop at him from all sides. But instead of using a controller, players must navigate by looking at arrows on the screen. They must also shoot the menacing birds using only their eyes.

It’s hard, says Blair, and also a lot of fun. An infrared eye tracker mounted underneath the computer monitor tracks the movements of the user’s eyes individually, eliminating the need to cover one, and can detect improvements as it’s used for treatment.

Another module of the game is used for diagnosis. In it, objects of various sizes move across the screen as the tracker assesses how long each eye takes to find each object and follow it. The team, competing in the Imagine Cup Innovation category, is testing their game in clinical trials.

“We’re offering a solution that’s affordable that can fix a problem that is personal to a lot of people,” Nassri says.

One of the most impoverished regions in Brazil was the inspiration for the four members of the Tower Up team, a finalist in the Games category. Ramon Coelho de Souza grew up in Araçuaí, a city in the drought-ravaged Jequitinhonha Valley.

He remembers the families, especially those in the region’s rural reaches, that struggled to survive on the limited amounts of water brought by government trucks that never seemed to come often enough. His recollections of life in the valley made teammates Daniel Sanabria, Alessandra Faria de Castro and Érico Grasso want to do something to help.

“I can’t imagine my life without water, and when he told us of the problems and we saw how that inspired him, that inspired us, too,” Sanabria says.

In their game, Jequi is a spirited young boy who must get past thorns, holes and other obstacles to collect water in hopes of saving his family and the entire valley from drought. He sees “the pain of his family, and he starts to create solutions in his imagination,” Sanabria says.

Called “Sonho de Jequi,” or “Jequi’s Dream,” the first-person runner is also designed to take people beyond the valley’s poverty to share the richness of its music, art and culture, Sanabria says.

De Castro and Grasso used watercolor paints to help create the visuals, but what makes the game especially unusual is that it offers a way to take action. The team partnered with Cáritas, an NGO that builds reservoirs and wells, to give players a way to donate money to help Jequitinhonha Valley residents, Sanabria says.

The team hopes the game can raise awareness and eventually help make a difference.

“It has always been my desire to make the world a better place after me,” de Souza says. “And knowing the need of where I come from, this is a good start.”

Part of what inspired Matija Srbić and Marija Cestarić’s project happened before Srbić was born. His mother was cooking in the family kitchen and stepped away to retrieve an ingredient. Srbić’s sister, then 2, grabbed some chocolate from the table. She was too little to chew it and started to choke.

Fortunately, Srbić’s mother returned in time to save the toddler, but hearing the story as he grew up had a big impact on Srbić. Accidental injuries and deaths that are all too common for young children are what he and Cestarić hope to prevent with their project, “Juvo – Home Friend.” The Croatian team, Home Guardians, is a World Citizenship finalist.

“Considering that children are less aware of the dangers in their own surroundings, parents are making a constant effort to ensure their kids safety by keeping them under constant supervision,” Srbić says. “We know this can be exhausting for parents.”

The team’s technology is intended to add another layer of safety. It consists of a Bluetooth-enabled bracelet, some smart sensors and a perky-faced plush toy called Juvo, a Latin word for “help” or “save.”

The system, which is powered by Microsoft Azure and a tiny Raspberry Pi device, works like this: The parent places the sensors in potentially dangerous areas of the house, such as the entrance to the kitchen or balcony, then puts the bracelet on the child and gives the child the stuffed toy.

When the child nears a sensor, it notifies the parent through a phone app. At the same time, it triggers a speaker inside the plush toy to sing a lullaby or play a recording of the parent’s voice, hopefully distracting the child for a few moments until the parent can get there.

Srbić says “Juvo – Home Friend” could be especially helpful in protecting children with developmental disabilities, but would be useful for parents of all children under age 3.

Cup World Finals, where they are hoping to make new friends and get new ideas for taking their project to the next level, he says. “We are very glad that we are one of the finalists.”

Lead photo: Ilias Chrysovergis, Georgios Schinas, Margarita Bintsi and Vasileios Baltatzis of Team AMANDA.