Read this story in Hindi, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Portuguese, Spanish or Tamil.

KANAKAPURA, Karnataka, India – In this five-room village school fringed by coconut trees, teacher Ravindra K. Nagaiah has a surprise for his 7th grade science class today.

The day’s topic is “Acids, Bases and Salts.” Along with the usual supply of litmus strips, hydrochloric acid and baking soda, Ravindra has prepared small beakers of juice from the hibiscus flower and from lemons. The students crowd around the table to watch one student mix lemon with hibiscus juice. The solution turns green, indicating acidity. Another student mixes baking soda and hibiscus juice, which turns pink.

Who knew, children, that hibiscus juice was a natural pH indicator?

Ravindra got the idea for the activity from Shiksha copilot, a generative AI digital assistant that draws up lesson plans – including activities, videos and quizzes – in minutes. The software is being developed with the non-profit Sikshana Foundation and tested in English, as well as the local Kannada language by 30 teachers in 30 schools in Karnataka state, with teachers reporting promising results.

Shiksha copilot is part of Project VeLLM, Microsoft Research India’s platform to develop specialized generative AI copilots that are accessible to everyone from teachers to farmers to small business owners. Shiksha means education in Sanskrit.

It is built on Microsoft Azure OpenAI Service and combined with the school curriculum and learning objectives. Azure Cognitive Service is used to ingest the text in textbooks including how the content is organized.

With Shiksha copilot, the researchers hope India’s army of overstretched government schoolteachers could soon get a break – and their students could enjoy livelier and richer lessons.

From the teacher’s perspective, the biggest benefit is the time saved preparing for class. Ravindra, who has taught science and math at the Government Higher Primary School Venkatarayanadoddi for 15 years, says he used to spend up to 40 minutes putting pen to paper to write a single lesson plan. “Now we can have a new lesson within 10 minutes,” he said.

In this school of five teachers and 69 students, whose parents mostly grow mangoes or rear silkworms for a living, resources can be scarce. So Ravindra modifies the plan as needed. If he doesn’t have materials needed for a suggested activity, he asks Shiksha copilot for another idea, specifying what he does have on hand. If a video is too long, he asks for a shorter one. He can also modify assignments and ask questions.

“The old method of chalk and blackboard is not sufficient anymore,” said Ravindra. “The time saved by Shiksha, I’m spending with the kids.”

Big class sizes

Creating lesson plans has always been laborious work. A teacher starts with government curricula, usually textbooks, then creates one based on the school’s resources, the make-up of learners and the teacher’s own ability and experience. If that’s not hard enough, now try capturing the attention of a generation fed on social media and online videos.

Here, teachers also grapple with bigger class sizes than elsewhere. In Indian primary schools, there is one teacher to every 33 students versus the world average of 23, according to UNESCO 2020 data. In China, the ratio is 1:16; in Brazil, it’s 1:20 and North America is 1:14.

In India, as people move from villages to cities, urban class sizes can balloon to between 40 and 80 students, according to the Bengaluru-based Sikshana Foundation.

Over the years, that has led even people with minimal incomes to resort to borrowing money to send their kids to private schools, said CEO Prasanna Vadayar.

Vadayar grew up in Karnataka and moved to the U.S. to pursue a master’s in computer engineering from Texas A&M University before starting a successful software business in Austin, Texas. He returned to India to head Sikshana in 2007 while on a sabbatical. He’s still here.

Sikshana Foundation’s mission is to reverse the exodus from government schools by raising the quality of education – permanently. “When people ask me why I joined Sikshana,” said Vadayar, “I tell them ‘to shut it down.’”

Sikshana is known for its low-cost, effective interventions that can be adopted by the government. It now works in six states across India, covering 50,000 schools and impacting three million students.

Its Prerana project, for example, provides opportunities for students to be peer leaders and rewards students for small, daily achievements, from regular attendance to doing well in academics and sports. Students get shiny stars of colored foil that they can collect and safety-pin to their shirts, and colorful stickers denoting lessons learned. Kids get motivated and parents can easily see what their child has achieved.

Prerana was adopted by the Karnataka government in 2018 and rolled out across the state.

A couple of years ago, Vadayar noticed how teachers were bogged down preparing for lessons and tried to find a solution but gave up, pending the right tech. In early 2023, when Microsoft Research India came knocking with Shiksha copilot, Vadayar remembers thinking, “Boom!”

Generative AI for the masses

In Microsoft, Sikshana found a partner with the tech solution it was seeking. In Sikshana, Microsoft found an avenue to test the solution in schools and hopefully, mass adoption, possibly beyond India.

“This is a global problem,” said Vadayar. “The learning ecosystem is not able to keep up with technology in the class and teachers are not able to keep up their learning chops. Kids expect something more.”

Akshay Nambi and Tanuja Ganu are researchers on Shiksha copilot at Microsoft Research India and have worked closely on other projects.

“A year ago, we wanted to look at how we could apply GenAI to solve real-world problems at population scale,” Ganu said. Added Nambi, “Shiksha copilot is a research vehicle for us to understand how users use them and get user feedback to improve the overall copilot experience.”

Generative AI tools are built on large language models (LLMs) that synthesize massive amounts of data to generate text, code, images and more. But results can be imperfect. In recent months, researchers have sought to improve accuracy by adding specific domain knowledge – in this case, the education curriculum of Karnataka state.

Retrieving information from that knowledge base cuts the risk of errors, said Nambi. That information is then brought into the LLM which generates the lesson plan. The copilot is multimodal, meaning it includes images and video as well as text, and draws publicly available videos from the internet. Finally, Azure OpenAI Service content filters and built-in prompts keep out inappropriate content, for example, racial or caste-related issues. Through it all, the teacher is the “expert in the loop,” Nambi said, with students having no direct contact with Shiksha copilot.

At the end of December 2023, the Sikshana Foundation surveyed the teachers on their experience with Shiksha. Five were from urban schools and 25 from rural schools. The majority were teaching in Kannada, with just six teaching in English.

The vast majority of respondents said Shiksha copilot cut their lesson plan preparation from an hour or more to between five and 15 minutes and 90 percent said they only needed to make minor modifications, if any, to the plans generated. Each teacher generated on average three to four lesson plans each week.

“Every class is becoming lively”

For the small cohort of teachers trying out the system, it’s already making a difference.

The Government Higher Primary School Basavanahalli in the town of Nelamangala on the outskirts of Bengaluru is an L-shaped building painted orange and lime green, with a dusty schoolyard where students from grades one to eight assemble and play. The school has 13 teachers, 438 students and an average class size of 30.

Science and math teacher Mahalakshmi Ashok, who has been testing Shiksha copilot, says it has freed up time for her to add activities in class.

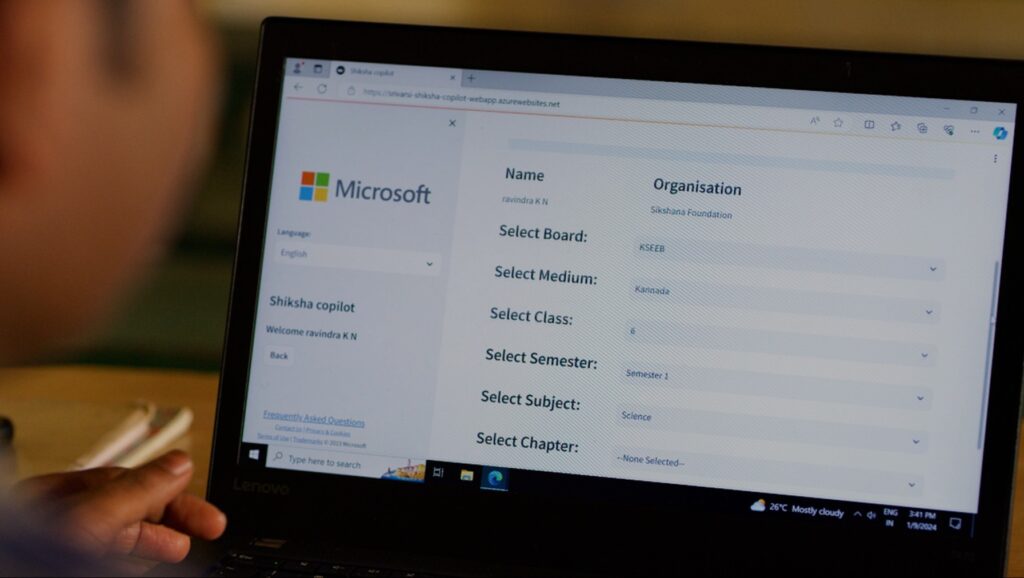

Sitting in the teachers’ meeting room, where the walls are lined with portraits of Karnataka notables, Mahalakshmi fires up her laptop and opens Shiksha copilot.

The first page is a series of fields with drop-down menus: Select education board, medium (English or Kannada for now, with other local languages to come), class, semester, subject (currently English, Math, Social Science and Science) and topic.

She picks Science, types “Circulatory System” and selects Duration: 40 minutes. Instantly, Shiksha copilot generates a lesson plan – with the option to generate a PDF, PowerPoint slides or handout – together with suggested activities, videos and assessment. After each sub-section, there is a choice of three emojis to rate what’s been generated.

In the past, Mahalakshmi said, when teaching the cardiovascular system, she might have drawn a diagram of a heart on the blackboard and talked through its function. Recently, she tried a new activity suggested by Shiksha copilot. Each student put a finger on their wrist to locate their pulse and measured the beats per minute. They compared results and discussed why some might have a faster or slower heartbeat than others.

One copilot-suggested activity – a blood-typing lab – was out of the question. But another activity – taking one’s blood pressure – might be possible. Mahalakshmi thinks she might bring a blood pressure cuff from home next time for the kids to try out.

“Obviously, they like these experiments,” said Mahalakshmi, who has taught for 20 years and is also the current acting head of school. “Each and every class is becoming lively. The learning has become easier.”

At a recent science class on “Separation of Substances,” she brought in small bags of rice, wheat, sand and water to illustrate the lesson. The class of 6th graders, wearing all-white uniforms, the girls with hair in looped braids, already knew the concepts. They yelled in unison as Mahalakshmi went through the motions, “Handpicking! Winnowing! Sedimentation! Filtration!” and so on.

Asked if she had taught this way before, she said “No,” cocked her head and added, “Because I’m getting more time, no?”

Beyond lesson plans

The next phase is to expand the pilot to 100 schools by the end of the academic year in March, said Smitha Venkatesh, chief program officer at the Sikshana Foundation. Then starting in April, the team will start curating the best-rated lesson plans, so teachers can modify existing plans instead of having to create new ones.

Smitha, who joined Sikshana 11 years ago after studying and working in the U.S., said she has come to understand the myriad challenges teachers face.

“There is the perception that government schools are not good,” she said. “But we acknowledge that teachers are doing so much more than just teaching. Not just make sure students learn, but also make sure they get their uniforms, make sure they have their meals, conduct census, etc. Shiksha copilot can help teachers deliver better within the time constraints.”

Perhaps in the future, Shiksha copilot can also help with other tasks such as scheduling classes or tracking learning, said Smitha. Maybe it can also help students who are struggling.

“AI is exciting, yes,” she said. “But at the end of the day, can it help the teacher, and can it help the child?”

Top image: Teacher Ravindra K. Nagaiah with his 7th grade science class at Government Higher Primary School Venkatarayanadoddi in Kanakapura, Karnataka state, India. Photo by Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Microsoft.