FARMINGTON, Wash. – The gently rolling hills here in eastern Washington have long grown rich harvests of wheat, barley and lentils.

Fifth-generation farmer Andrew Nelson is adding a new bumper crop to that bounty: Data.

He gathers it from sensors in the soil, drones in the sky and satellites in space. They feed Nelson information about his farm at distinct points, every day, all year long — temperature variations, soil moisture and nutrient levels, plant health and more.

Nelson in turn feeds that data into Project FarmVibes, a new suite of farm-focused technologies from Microsoft Research. Starting today, Microsoft will open source these tools so researchers and data scientists — and the rare farmer like Nelson, who is also a software engineer — can build upon them to turn agricultural data into action that can help boost yields and cut costs.

The first open-source release is FarmVibes.AI. It is a sample set of algorithms aimed at inspiring the research and data science community to advance data-driven agriculture. Nelson is using this AI-powered toolkit to help guide decisions at every phase of farming, from before seeds go into the ground until well after harvest.

FarmVibes.AI algorithms, which run on Microsoft Azure, predict the ideal amounts of fertilizer and herbicide Nelson should use and where to apply them; forecast temperatures and wind speeds across his fields, informing when and where he plants and sprays; determine the ideal depth to plant seeds based on soil moisture; and tell him how different crops and practices can keep carbon sequestered in his soil.

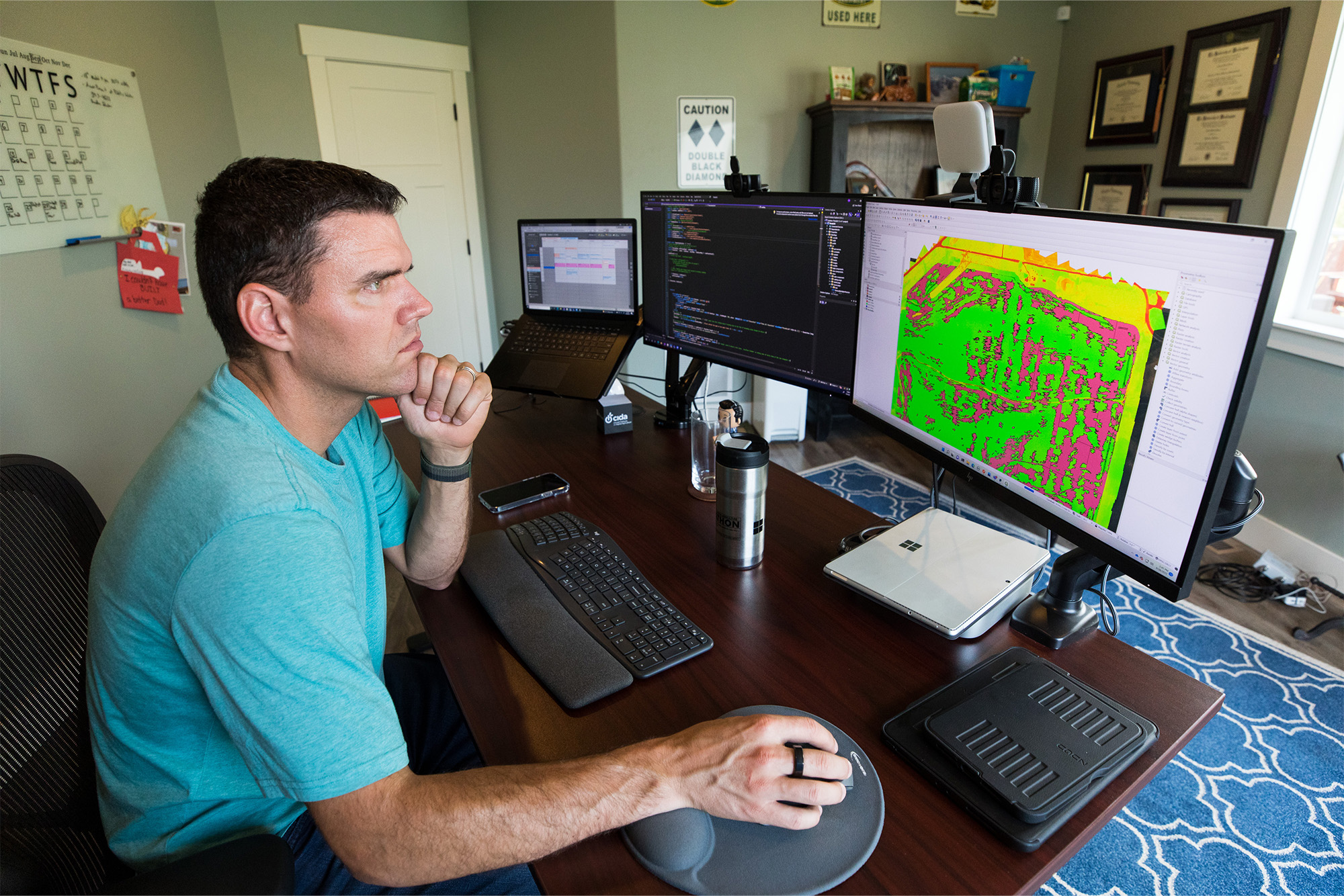

Andrew Nelson studies a FarmVibes.AI image identifying grass weeds in one of his fields. It was created from multispectral drone imagery and will inform Nelson’s treatment decisions later this fall. (Photo: Dan DeLong for Microsoft)

“Project FarmVibes is allowing us to build the farm of the future,” said Nelson, who has partnered with Microsoft Research to turn his 7,500 acres into a proving ground for Project FarmVibes. “We’re showcasing the impact technology and AI can have in agriculture. For me, Project FarmVibes is saving a lot in time, it’s saving a lot in costs and it’s helping us control any issues we have on the farm.”

The new tools sprouted from Microsoft’s work with large customers like Land O’ Lakes and Bayer to integrate and analyze data. Project FarmVibes reflects more recent research in precision and sustainable agriculture.

By open sourcing its latest research tools, Microsoft wants to spread them far beyond Washington to help tackle the world’s urgent food problem, said Ranveer Chandra, managing director of Research for Industry.

By 2050, we’ll need to roughly double global food production to feed the planet, Chandra said. But as climate change accelerates, water levels drop and arable lands vanish, doing that sustainably will be a huge challenge.

“We believe one of the most promising approaches to address this problem is data-driven agriculture,” he said.

At Microsoft, we are working to empower growers with data and AI to augment their knowledge about farming and help them grow nutritious food in a sustainable way.

Research bears fruit

Until recently, Nelson’s farm was like many others around the world. He had internet in his home, but the Wi-Fi signal ended outside his door. His 7,500 acres were a dead zone.

Now he’s using a Project FarmVibes solution, called FarmVibes.Connect, which will eventually be open sourced by Microsoft to bring connectivity to remote and rural places. It delivers broadband access via TV white spaces, the unused spectrum that flickers as “snow” between channels. Today, Nelson has a solar-powered TV white spaces antenna that acts like a Wi-Fi router, but one that can cover most of his farm.

That connectivity has allowed him to glean insights from the FarmVibes.AI suite. Now available in GitHub, FarmVibes.AI includes:

-

- Async Fusion, which combines drone and satellite imagery with data from ground-based sensors to offer insights. For example, Nelson uses Async Fusion to create nutrient heat maps from multispectral drone imagery and data from soil sensors. These maps are used to vary the rate at which he plants seeds and applies fertilizer, which can increase yield and prevent overfertilization. Async Fusion can also create soil moisture maps from sensor data across Nelson’s farm. These maps tell Nelson how deep to plant his seeds, and in what order he should plant his fields. As a bonus, they can help prevent tractors and sprayers from getting stuck in muck.

- SpaceEye, which uses AI to remove clouds from satellite imagery. This helps Nelson fill in the gaps for areas he hasn’t scouted with a drone. He can then feed these images into AI models that can identify weeds, helping him create maps to deliver herbicide only to areas that need them. And even when he does spray, these maps let him vary the rate of application, delivering more volume to densely weedy patches and a lighter load elsewhere.

- DeepMC, which uses sensor data and weather station forecasts to predict temperatures and wind speeds for his farm’s microclimate. In Nelson’s area, the local weather forecast predicts what conditions will be like 10 meters off the ground. “Well, I don’t care what it is 10 meters off the ground,” he said. “I care about what it is where my crops are.” Earlier this spring, Nelson was preparing to spray his wheat fields. He checked forecasts for the right weather window; the plants would be harmed by the herbicide if he sprayed in freezing temps. The local forecast looked promising, but DeepMC predicted a freeze. He held off spraying – and woke up to frost.

- A “what if” analytics tool that estimates how various farming practices would affect the amount of carbon sequestered in the soil. Today, Nelson uses these “what if” scenarios to improve the health of his soil and boost yield. But he plans to use them to enter carbon markets, which pay farmers for practices that keep carbon dioxide locked up in soil rather than entering the atmosphere.

Nelson is currently testing other Project FarmVibes tools beyond FarmVibes.AI that will be open sourced in the future. This includes FarmVibes.Edge, which intelligently compresses large amounts of data from drone scouting flights. It identifies the areas a farmer cares about — weeds in a field, for instance — and ignores other details like roads. This lets FarmVibes.Edge efficiently construct images small enough to be uploaded to the cloud via FarmVibes.Connect.

Collectively, these technologies are making a big impact both in his fields and his bank account. For example, the first year Nelson used data to guide his spraying, the amount he saved was exactly the amount he earned. Earlier this spring, he applied the approach to one-third of his fields and saved nearly 35% on one of his most-used chemicals. After the fall harvest, he estimates saving an additional 40%. “That’s an employee,” he said.

Nelson continues to test new Microsoft Research technologies. One of the latest is traceability sensors, which follow Nelson’s crop from field to truck to storage bin. Inside the grain silos, these sensors will help Nelson keep tabs on carbon dioxide levels. If those start to rise, it’s a sign too much moisture is hiding inside, and Nelson will know to turn on giant fans to protect his crop. Later, the sensors will help track the crop, ensuring that a particular variety of wheat bound for, say, Asia is on the right truck headed for the right barge along the Snake River.

From sickles to spreadsheets

AI algorithms like Async Fusion, SpaceEye and DeepMC could not only help farmers adapt to a changing climate, Chandra said. They could help tackle it. By reducing how much water and chemicals farmers use, he said, technology can boost productivity in a sustainable way.

Meanwhile, the “what if” analytics tool in FarmVibes.AI can potentially help farms remove carbon that contributes to global warming, Chandra said.

“Agriculture is a cause of climate change, it is most impacted by climate change, but with help from technology it can also be a solution to climate change,” Chandra said.

Andrew Nelson, the rare farmer who is just as comfortable coding as on a combine, reviews multispectral drone imagery in his office. (Photo: Dan DeLong for Microsoft)

Chandra notes that most farmers around the world aren’t like Nelson, who is as comfortable coding as he is on a combine. Most won’t download these tools on GitHub. Instead, Microsoft wants to inspire academic and industry partners to translate this research into tools that can be used by all farmers, including the smallholder farms in the developing world.

We want to empower the experts with all the latest in technology so that they can take their domain knowledge and start building tools for growers.

“That’s why we’re open sourcing – to make this available to the community so that they can bring the best in soil science to the best in computer science to unlock the opportunity to help enable sustainable agriculture.”

Farmers have always turned to technology to squeeze more out of the soil, Nelson said. So he doesn’t see a huge leap from sickle and scythe to software and spreadsheets.

“I think it’s just like how computing has progressed: Everything keeps building on everything that came before,” Nelson said. “With more powerful equipment, I can farm 7,500 acres where my grandfather farmed 750. With Project FarmVibes, technology is helping me get back to farming on that smaller scale – acre by acre, instead of field by field – because I have such a fine-grained understanding of the land.”

Related:

- Learn more about Project FarmVibes

- Download FarmVibes.AI from GitHub

Jake Siegel writes about Microsoft research and innovation.

Top image: Andrew Nelson launches a drone from the back of his pickup truck to take multispectral images of a field to document drainage and the amount of fall weeds. (Photo: Dan DeLong for Microsoft)