Meet me in the trees: new outdoor meeting spaces help employees reap the benefits of nature

Treehouse conference rooms help Microsoft evolve the modern workspace

Wi-Fi? Check. Power for your tablet or PC? Yep.

Bird calls? All around.

To get to Microsoft’s most unexpected new meeting space, embark on a leisurely outdoor stroll up a planked, accessible switchback ramp. At the top, a secure wooden gate swings open to reveal a deck suspended by timber beams and cables. A minty pine perfume infuses the air. Two angled cedar awnings jut out from tree trunks, protecting employees from the elements.

But the elements are why people come here—up into a majestic Pacific Northwest Douglas fir, where a collaboration room is built inside a treehouse.

Aloft, the usual corporate sounds of clicking doors, conference calls, and heels on concrete melt away. A fall wind sweeps through emerald branches. Every once in a while, a pinecone drops to the deck with a soft thud. A sudden ruckus breaks the gentle morning hush: a squirrel scrambling for breakfast charges across the arms of nearby hemlock and western red cedar.

Welcome to a new kind of workspace that’s helping employees benefit from what science shows is the powerful impact of nature on creativity, focus, and happiness.

An audio description version of the above video is also available.

The treehouse is one of three new branch-based meeting spaces created by renowned builder Pete Nelson of Nelson Treehouse and Supply. Nelson kicked off the project by spending his first day on the site “connecting with the trees” for hours, said Bret Boulter, who works in Real Estate & Facilities on Microsoft’s Redmond campus and who headed up the project.

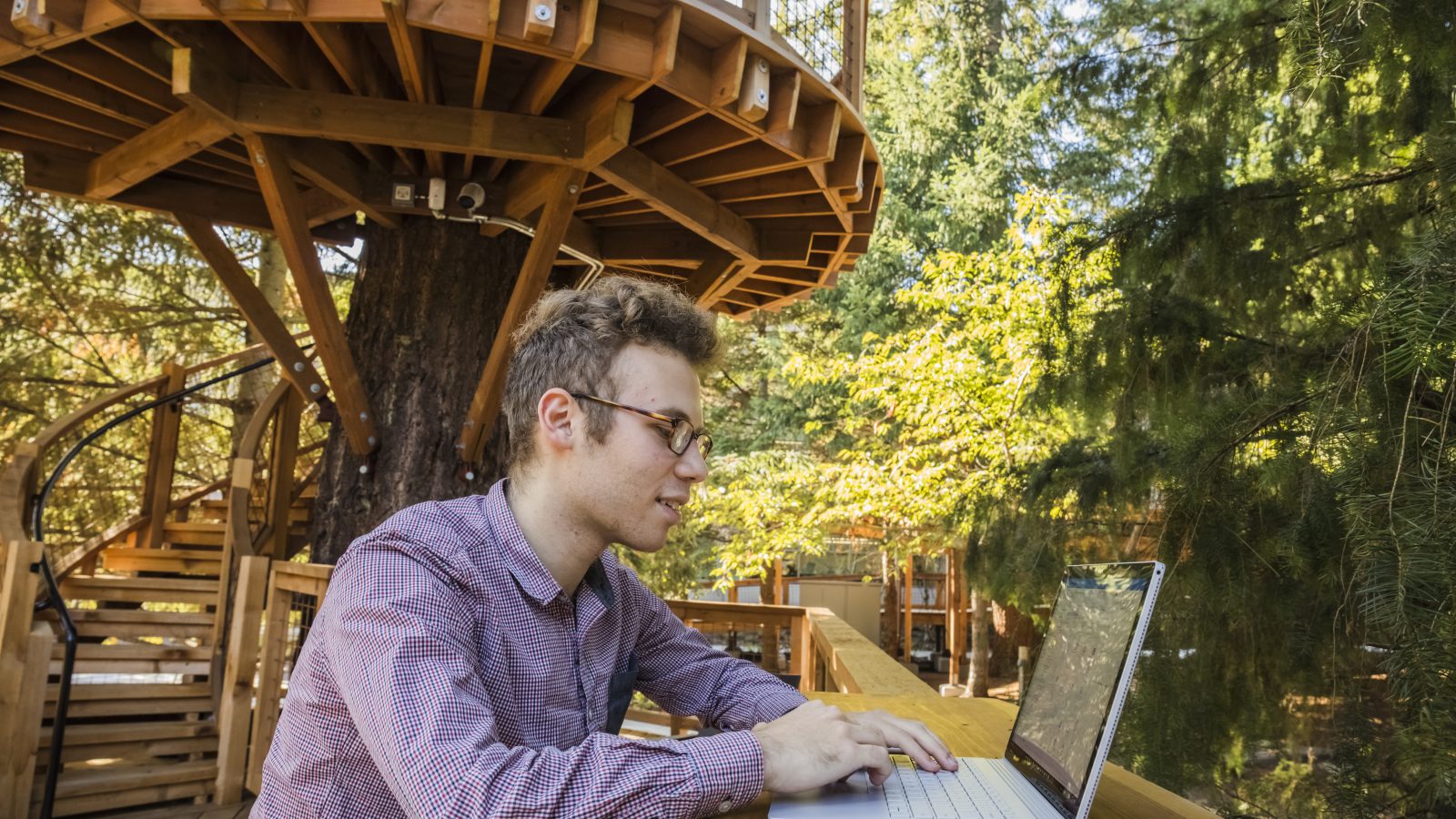

The treehouses are part of a larger new system of technology-enabled outdoor districts connected to buildings around campus and empowering employees to work in new ways. On a recent sunny day, an employee perched, legs crossed, on a soft grassy knoll below a treehouse. For several minutes, she sat with her hands on her knees, eyes closed, head tilted toward the sky, breathing deeply. Then she grabbed her laptop and typed furiously. After a spate of work, she set her computer aside, rested her palms on her knees, gazed up, and then closed her eyes again.

While under construction this summer, the outdoor meeting spaces, which include two enclosed treehouses and one elevated roost called the Crow’s Nest, created a wave of curiosity.

“It beat out all rumors,” said Shanon Bernstine, a business manager who helped plan the spaces. “People didn’t believe it was really happening: there was a lot of excitement.”

Twelve feet off the ground, treehouse number one features charred-wood walls and a soaring ceiling with a round skylight that lets in just a bubble of blue. It’s more Hobbit than HQ, with cinnamon-colored shingles and a gingerbread-house feel.

A hand-carved arched double door glides open at the swipe of a badge. The almost mustardy fragrance of rough-hewn cedar is instantaneous. Inside the small room nests a simple farmhouse table with rust-red seats. Box benches line the reclaimed-wood walls, dark as campfire smoke.

There’s no AV system or calibrated climate control. But what happens when people enter is a kind of magic.

“The first thing when you walk into the space is that everyone is really quiet. You stop talking and are just present,” said Boulter. “It’s fascinating. People absorb the environment, and it changes the perception of their work and how they can do it.”

“We don’t have to bring nature to urbanity—we are in nature. It’s at our back door.”

Built for biophiles

Scientists have found plenty of connection between exposure to outdoor spaces and people’s well-being. Nature “stimulates reward neurons in your brain. It turns off the stress response, which means you have lower cortisol levels, lower heart rate and blood pressure, and improved immune response,” wrote Harvard physician Eva M. Selhub, coauthor of Your Brain on Nature. Exposure to nature has been found to increase positive feelings, creativity, and focus and to restore the mind from the mental fatigue of work. Forests have a particular impact on people. “Trees and plants secrete aromatic chemicals that impact our cognition, mental state, and even our immunity,” Selhub wrote.

The treehouses are part of a larger redesign that makes working in nature easier than it’s ever been. When it set out to renovate the spaces outside Buildings 30–32—the first in a series of similar campus projects planned—the design team surveyed employees to see what they cared about most.

“People said, given the opportunity, they would work more outside,” Boulter said.

While some companies have moved toward the trend of creating green indoor spaces that function as proxies for the outdoors, Microsoft has something unique that most companies located within large metropolitan areas don’t have: a 500-acre campus nestled in the woods, with greenspace and wildlife galore.

“We don’t have to bring nature to urbanity—we are in nature. It’s at our back door,” said Boulter. Many employees who come to the region from elsewhere are drawn to the eco ethic and recreational opportunities; longtime Pacific Northwest residents feel a kinship with and comfort in nature that can be summed up by this fact: we barely see the need for umbrellas in the rain.

That relationship to nature is rooted in the company’s history. Four years after it was founded in New Mexico, Microsoft made the jump to the Pacific Northwest, filling a series of buildings in the region while realizing it needed a long-term strategic plan for growth. A guiding document laid out five criteria for a headquarters, including this: provide an attractive “park-like” location for employees.

The evolution of outdoor meeting space emphasizes this long-ago envisioned connection to the environment while increasing opportunities for workers to collaborate—all while maintaining the reliable connectivity of a traditional office. A broad outdoor Wi-Fi network allows employees to range; every bench is weatherproof and contains a hatch that reveals electricity sources. The indoor cafeteria is extended outside, with a barbecue restaurant built into a shipping container. Tactile surfaces help people who are blind or have low vision navigate. The space has rust-proof rocking chairs; an outdoor gas fireplace that brings the warmth of a ski lodge and attracts an after-work crowd; and a weatherproof awning that, when the sun shines, stencils the Microsoft logo onto the manicured lawn. Many materials are local or reclaimed, and with its abundant wood canopies and steel accents the space pays homage to the site’s history as a former sawmill.

It’s all to help employees work seamlessly and better interact with one another, including via spontaneous encounters. “We want to bring more human touch back into the workplace,” Boulter said. “For people to be the most productive and create the best products, we want them to have that opportunity for collaboration. Any employee can take their device outside, have a meeting—even in a treehouse—and be just as productive.”

“We made sure we were intentional about how we made the space,” said Genise Dawson, an executive business administrator who helped plan the outdoor district for Buildings 30–32. “And people love it. Even though it rains, they still sit out there.”

From fun to focus

Two of the three treehouses, which are accessible to all employees, are open. The cedar meeting room takes reservations, as with many of Microsoft’s more traditional meeting spaces; the Crow’s Nest is first-come, first-served. The third, a sheltered lounge space, will be ready later this year. The building is already taking shape in the boughs of a tree Pete Nelson selected—”Nothing formal,” said Dawson. “A place you can chill inside or out of, sit, work.”

Curious employees are coming from around campus to see the treehouses for themselves. “One employee who booked it for a two-hour meeting told me, ‘We got a lot done in a very different way,'” Bernstine said.

With their workspace turned inside out and meetings taking place up in the foliage employees are figuring out how to rethink what working looks like.

“A lot of people are like, ‘where’s the AV?’ And I’m like, it’s a treehouse,” said Boulter. “We wanted people to intentionally unplug, because they are sitting in front of screens all day long.”

The buildings are made to flex and expand as the trees grow, and while they will hopefully last at least 20 years, said Boulter, they will have a finite lifespan, “like any living thing.”

As workers see what nature has to offer, Bernstine said, horizons are already being expanded.

“Being more creative and flexible with our workspace allows us to be more creative and productive in our work and the products we create. It’s like a little getaway.”