You don’t have to be a developer to turn a great idea into an app

As Lauren Taylor thought about student reading assessments at her school, she saw a fundamental problem.

Teachers at Manitou Park Elementary School in Tacoma, Washington, where Taylor is the vice principal, were recording data from the assessments three times a year on paper. Scores for each student were then entered into a database and students were grouped based on those scores. The approach meant detailed information about students’ reading abilities wasn’t available without sifting through reams of paper, which made it difficult to determine what each student needed to learn and improve.

Assistant school principal Lauren Taylor (Photo by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures)

Taylor, who had little tech background, initially laughed at the suggestion that she could build an app to solve the problem. But she eventually dug into PowerApps, a platform designed to make it easy. She created a way for teachers to enter reading assessment information, store it in a SharePoint list and track students’ progress through Power BI data charts.

Teachers can now easily access the app and data through Teams, Microsoft’s chat-based collaboration hub, on their phones or tablets and do a better job of meeting the needs of students — and Taylor says it was all surprisingly easy to do.

“It’s not ‘I wish someone could make this’ anymore,” she says. “It’s ‘What do I want to make? I know it can happen, and how do I get it there?’”

Taylor is one of many people around the world who are using Microsoft tools, platforms and online communities to build apps and solutions that were once exclusively the purview of professional developers. That idea of empowering developers of all skill levels is a central focus of Microsoft’s Build 2019 conference May 6-8 in Seattle.

The annual event attracts software engineers and web developers, and will have a wider audience this year, when for the first time Build attendees can register to bring kids aged 14 and up to the conference to learn and explore for free, and students from around the world will be competing in the Imagine Cup World Championship hosted at Build for the first time.

Charlotte Yarkoni, corporate vice president of Microsoft Commerce + Ecosystems, says Build 2019 is a reflection of what it now means to be a developer — that with the right tools, anyone can use technology to build something extraordinary.

“Microsoft has a broad range of platforms that help people build apps, solve problems and create great things with technology — and they’re not just for experienced coders and engineers,” Yarkoni says. “Whether you’re a high school student with a big idea or a seasoned computer scientist, tools like VS Code, Azure and GitHub can help you bring your ideas to life.”

Red Cross employee Nick Gill had little tech background before developing an app to help with ordering supplies for teaching classes. (Photo courtesy of Nick Gill)

Nick Gill, a training specialist for the American Red Cross, had little knowledge of technology when he decided to tackle a challenge facing the organization’s instructors, who were using a paper-based process to order supplies needed for teaching classes. The forms were sent to a logistics coordinator who ordered the supplies, such as textbooks and bandages, but instructors never knew when the supplies would arrive, and supervisors had no idea about what was being ordered each month.

“That’s when it really hit home for our leadership that gosh, this isn’t working,” says Gill, who’s based in Dayton, Ohio. “We needed to be able to answer some very basic questions, and we weren’t able to do so because we were sitting here with pen and paper.”

Gill taught himself to use Power BI, PowerApps and Flow, which automates tasks across different apps, and created a shopping cart app for instructors to order supplies. The app automatically sends updates to instructors on the status of their orders and has shortened order cycles from three to four weeks to four or five business days, Gill says. Other Red Cross workers have also created apps, including a tool to connect people arriving at the same destination so they can share rental cars and a check-in app for volunteers working at disaster sites.

“It’s not ‘I wish someone could make this’ anymore. It’s ‘What do I want to make?’”

–assistant principal Lauren Taylor

Several Red Cross volunteers around the country now meet regularly on Skype or Teams to work on developing tech solutions to address organizational challenges. The growing culture of innovation has helped to better engage the Red Cross’s largely volunteer workforce, Gill says.

“We struggle at times to engage volunteers in things they’re interested in,” he says. “People might not be able to respond to a scene, but they can sit at their computer and create an app.”

Gill, who’s now the national manager of service delivery logistics and inventory for the Red Cross, is working on other apps to help track the organization’s equipment and manage its warehouse inventory. He says PowerApps provided a “gateway to learning” that prompted him to delve into other technologies that he wouldn’t have otherwise.

“PowerApps is accessible to the average person,” he says. “If you can click on the tile, you can make a PowerApp.”

Fabian Bolin, right, launched WarOnCancer with friend Sebastian Hermelin to help fellow cancer patients deal with emotional issues and share their stories. (Photo by Ema Persson)

For others, the impetus for creating tech solutions is more personal than professional. Fabian Bolin was 28 and pursuing a career in the film industry when his life was upended by a leukemia diagnosis. Unable to work for two and a half years while undergoing chemotherapy, Bolin was devastated. He started a blog about his battle with cancer and found that writing helped him process and normalize his situation. But it was the authentic connections with other cancer patients that most impacted Bolin.

“I’ve never felt happier than when I was writing the blog,” says Bolin, who lives in Stockholm, Sweden. “Knowing that my sharing helped others in their cancer journeys led to a bigger sense of meaning and purpose than I’ve ever felt before.”

Seeing an opportunity to help fellow cancer patients deal with depression and other emotional issues, Bolin enlisted the assistance of a friend, Sebastian Hermelin. The pair founded WarOnCancer.com as a social network for people with cancer. In March of this year, they launched an Azure-powered mobile app designed to allow cancer patients to share stories and experiences and find common ground. The app will also allow patients to share their data and track how it is being used in research, with the goal of helping connect them with effective treatment and clinical trials. Microsoft is collaborating with WarOnCancer, and Microsoft technologies will be used to develop the platform’s data component.

“We’re using digital technology, but the kids are building it with their hands. They’re not sitting staring at their screens.”

–educational technology and innovation specialist Stu Lowe

Bolin believes that by empowering cancer patients to contribute to research and make informed decisions about their care, facilitating what he calls “altruistic happiness,” WarOnCancer can help improve their mental health.

“We’re turning data-sharing into a value proposition with cancer,” he says. “We can look at it as a platform for cancer and trying to solve mental health issues, or we can look at it as a platform for mental health, and cancer is the test group.

“You could apply the same methodology to all forms of diseases to make sure people are feeling good again,” Bolin says. ”There’s no limit to what we possibly can do.”

(From left to right) University students Partoo Vafaeikia, Kathrine von Friedl and Elaheh Jalalpour created their SafeTrip app to help prevent car accidents. (Photo courtesy of SafeTrip team)

Personal experience also provided the motivation for SafeTrip, a contender in this year’s Imagine Cup. Created by an all-women team of Canadian university students, the app tracks drivers’ eye movements and notifies an emergency contact if a driver is falling asleep.

For team member Partoo Vafaeikia, a computer science student at the University of Toronto, the need for the solution is acutely real. She lost two friends within a week a few years ago in separate car accidents late at night. One vehicle crashed into a light pole; the other went over an embankment.

“It’s very important that we try to find a way to decrease these kinds of accidents and have safer roads,” Vafaeikia says.

The SafeTrip app takes a photo every second and sends it to a backend that uses Azure Custom Vision, which employs a machine-learning solution to recognize specific content in images, to determine whether the driver’s eyes are closed for three seconds or more. If they are, the system sends the vehicle’s latitude and longitude and a notification to an emergency contact and the app emits a loud sound to alert the driver.

“We looked at frameworks from other companies, and Microsoft’s was superior in terms of being more customizable, flexible and easy to use.”

— SafeTrip team member Kathrine von Friedl

The team members created SafeTrip during a hackathon at the University of Toronto after attending a Microsoft session where they learned about Azure Custom Vision. The technology was surprisingly easy to use, team member Kathrine von Friedl says.

“We realized that with Azure Custom Vision, we could just upload photos and it would train the model for us,” says von Friedl, who’s studying mechatronics engineering at the University of Waterloo. “We looked at frameworks from other companies, and Microsoft’s was superior in terms of being more customizable, flexible and easy to use.”

SafeTrip currently uses text notifications, but the team is looking into expanding to other messaging methods such as Skype and wants to leverage Bing’s map application programming interface to map drivers’ locations. The goal is to eventually partner with ride-sharing companies “that can benefit from it by guaranteeing safety for customers,” von Friedl says.

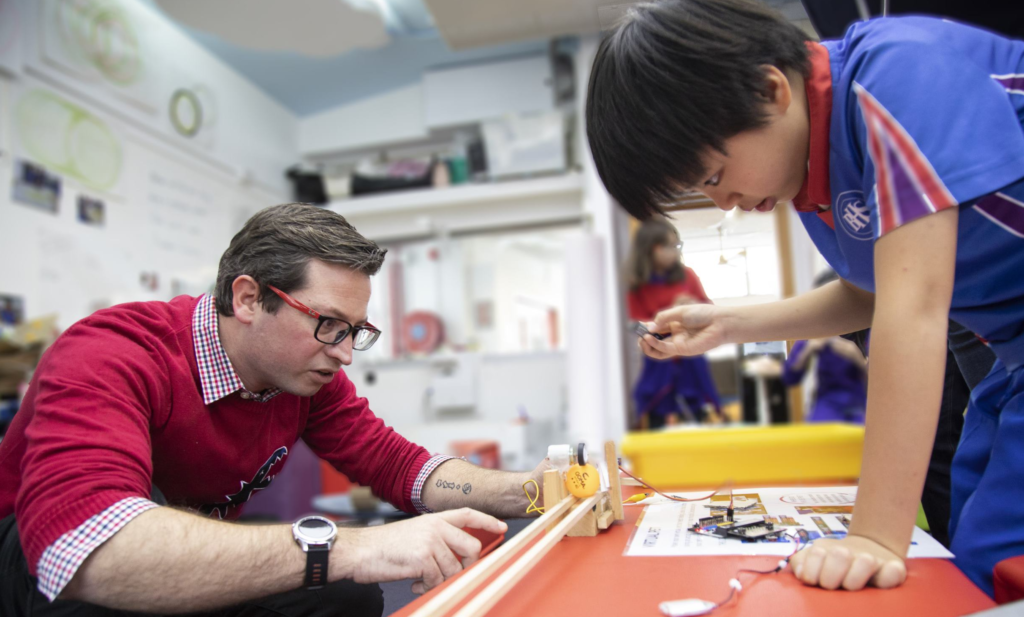

Stu Lowe, left, uses technology to foster a maker-centered learning approach for students and teachers at Beacon Hill School in Hong Kong. (Photo courtesy of Stu Lowe)

In Stu Lowe’s world, technology is a tool for learning and creating, for tinkering and bringing inventions to life. As the educational technology and innovation specialist at Beacon Hill School in Hong Kong, Lowe works with teachers and students aged 4 to 11 on maker-centered learning — using technology to make items related to topics they’re learning about. Students use Microsoft’s MakeCode platform and microcontrollers to create items ranging from smart backpacks with step counters to virtual pets, a ping pong ball cannon and a robot with eyes that change color.

The school previously taught students coding during 45-minute lessons, but that wasn’t long enough for them to do much with those skills, Lowe says.

“We spent a long time hammering on coding, but we had to take a reflective step back and say, ‘Well, what are we doing this for? The kids are getting good at it, but what’s the end game?’” he says. “Not everyone’s going to be a computer scientist. The kids have got these skills, but they’re not making anything with them.”

Two years ago, the school shifted from short coding lessons to incorporating tech-based building into each learning unit. It also started “teacher tinker days” led by Lowe that allow teachers to work on tech projects they might later bring to their students. Maker-centered education, Lowe says, aims to enhance learning through creative experimentation, empower children to become makers and encourage them to look more closely at objects and systems in their surrounding world and find ways to improve them.

“Microsoft has a broad range of platforms that help people build apps, solve problems and create great things with technology — and they’re not just for experienced coders and engineers.”

–Microsoft CVP Charlotte Yarkoni

Lowe says MakeCode — designed to create code that can be used inside robots, wearable items or whatever students want to invent — is accessible even for primary-aged children and has transformed how the school teaches coding. And building with microcontrollers really captures kids’ imaginations, he says.

“We’re using digital technology, but the kids are building it with their hands,” he says. “They’re not sitting staring at their screens.”

A lifelong maker who frustrated his parents as a child by taking his toys apart to see how they worked, Lowe also creates at home with technology, making video games and hacking furniture. He sees tinkering with technology as a way to prepare children for a world that, despite advances in technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning, will still require ingenuity and imagination.

“I think there’s a world in the future for people who are more creative,” he says.

Lead photo: Assistant principal Lauren Taylor works with students at Manitou Park Elementary School in Tacoma, Washington. (Photo by Scott Eklund/Red Box Pictures)