Children’s Mercy app brings doctors home, virtually, with babies born with heart disease

When Autumn Parkinson was 26 weeks pregnant, her doctor asked her to come back in for another ultrasound to make sure her baby’s heart didn’t have only one ventricle, a serious congenital disease called Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS). Parkinson, who has two other healthy children, researched HLHS but didn’t dwell on it too much.

“The disease was so rare and severe that I never considered it would be in our future,” she says. “We thought maybe they just hadn’t seen the ultrasound properly.”

Four months later, after surgery and an eight-week stay at Seattle Children’s Hospital for her newborn, Job, she and her husband found themselves back home in a rural area of Tacoma, Washington, with a medically fragile infant who needed constant monitoring until his next surgery in six months. Parkinson knew from HLHS support groups she’d found online that most parents had to take painstaking records daily in a three-ring binder and phone them in to their doctors to watch for complications, and even then, as many as 25 percent of the babies would die before their second surgery.

But thanks to the vision of a technologically minded doctor and his team in Kansas City, Missouri, 1,900 miles away, Parkinson has been able to relax into the routine with the comfort of knowing her baby’s cardiologist and nurse are looking over her shoulder every day, via the cloud. An app conceived by Dr. Girish Shirali, a pediatric cardiologist at Children’s Mercy hospital in Kansas City, has already saved babies and made life easier for their worried parents, and now it’s expanding across the country and being contemplated for other diseases as well.

“We focused on this disease because it’s the one where we knew the outcomes were really bad,” Shirali says. “But it quickly became clear that there are plenty of other conditions we can use it for, too.”

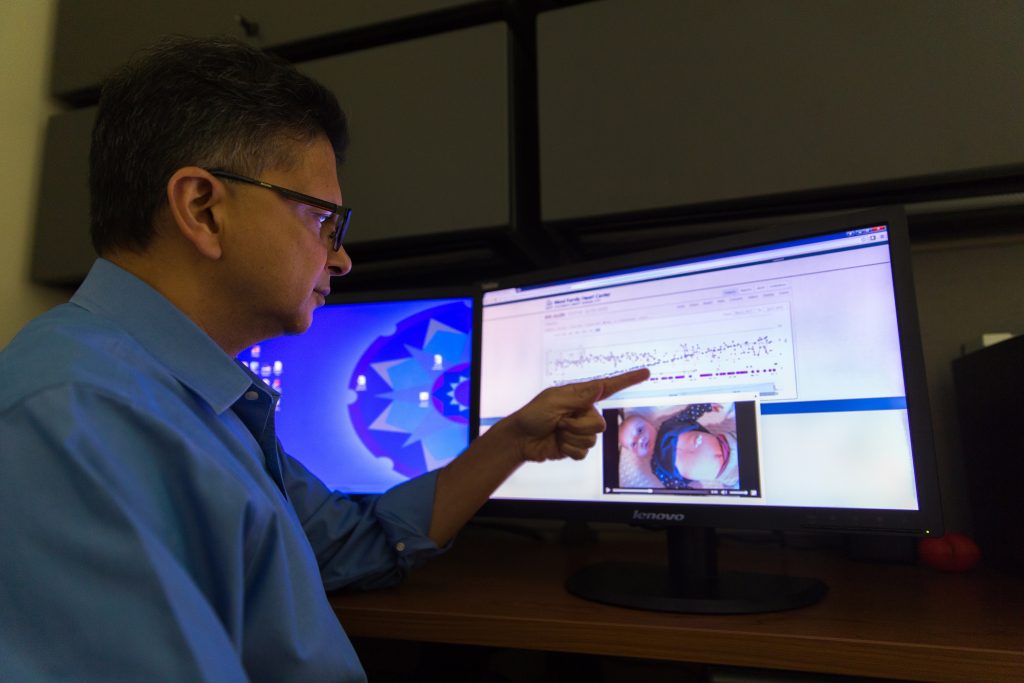

Shirali’s Cardiac High Acuity Monitoring Program, or CHAMP, consists of a Microsoft Surface 3 tablet with the Windows 10 operating system, connected to a database that sits in the Microsoft Cloud. The family enters the baby’s information in the app throughout each day, and the figures are instantly analyzed in the cloud. If there are any measurements outside healthy cardiac parameters, such as oxygen saturation that’s too low or high, the baby’s medical team is automatically alerted. There’s also an “I’m concerned” box parents can click that will immediately page the nurse.

It’s been a success with 62 patients in Kansas City so far, and now 16 families in Seattle are using it.

Before the app and tablet were introduced, parents would check various vital signs at home, such as heartrate, weight and oxygen saturation, that are important indicators of cardiac health, and then it was up to them to provide that information to the hospital each week over the phone. Otherwise nurses would try to track down the parents to find out if they were concerned about anything.

“It was a reactive model,” says Lori Erickson, a nurse practitioner and the clinical coordinator for the CHAMP program. “Now it’s become proactive. I can see every piece of data within two minutes as it goes from the tablet to the cloud, and even if there are no alerts, we look through the reports every day. We can catch things before parents do, because we’re the ones who are medically trained, and that’s the way it should be, to reduce the burden on the parents.”

Erickson says she was doubtful when the hospital first began using CHAMP, because she thought the team’s care was already really good. But by the third patient, she was hooked on the ability to monitor the babies daily and felt nervous without the app. No baby with this disease under Children’s Mercy’s care has died since CHAMP was adopted in 2014.

“If we follow 30 kids a year, that’s a whole kindergarten class that was saved, and that’s crazy,” Erickson says. “We didn’t know what we didn’t know before and didn’t realize that we were missing trends due to only getting numbers once a week.”

CHAMP is not only saving lives, it’s reducing costs, too.

Babies with this disease are the most expensive patients in the cardiac clinic, Erickson says, and are in the hospital the longest. But with the extra data she now has access to, she’s been able to modify treatments, warding off problems and avoiding readmissions to the hospital. She recently noticed a change of pattern in weight gain for one baby, and she says that three years ago, she would have admitted him to the hospital. With CHAMP, she was able to analyze his information from afar and have the parents alter his food intake, and a few days later all was well.

“The goal is to not let it get to an emergency event,” she says.

It also helps with families’ schedules. Some of Erickson’s patients live a five- or six-hour drive away from Kansas City, so avoiding unnecessary visits spares them a full day’s trip – or even a flight, in the case of Seattle Children’s, which serves a cluster of states as far away as Alaska. Parkinson, who uses the word “comfort” frequently when talking about CHAMP, lives more than an hour’s drive from Seattle Children’s. With a fragile baby and two rambunctious boys at home – Ezra, 5, and Isaac, 3 – she’s grateful to have a virtual nursing staff in her living room to help avoid the trek north when possible.

The app’s simplicity also allows Ezra and Isaac to be involved in baby Job’s care, Parkinson says. She calls out measurements to them after taking Job’s vitals, and they find the corresponding numbers to push on the touch screen. Doctors and nurses back at the hospital log into a web-based site to view their patients’ charts and the videos the parents have recorded, which are all stored on the cloud.

Shirali came up with the idea in 2012, as tablets were becoming popular. He sketched out his concept and showed it to the heart center’s informatics director, Richard Stroup, who wrote all the functional specifications and brought on a software architect to begin development. Shirali and Stroup are already looking at ways their center’s small IT group can modify CHAMP for children with heart failure and those who have recently received a heart transplant. Down the road, it could be used for adults with cardiac issues as well.

“We’re very excited about this because we’ve got four years under our belt now and have learned lessons,” Shirali says. “What we are trying to build is a system that will become smarter over time.”

Shirali and his team are working on algorithms that could use particular combinations of things like weight, saturation change and heartrate, for example, to help identify problems and improve the treatment plan.

“Maybe with smarter analytics, we’ll realize there are softer thresholds that will let us treat the baby quicker and even avoid hospitalization altogether,” Shirali says. “Rather than the analysis simply telling us that saturation is low, it could instead tell us that the risk of an adverse cardiac event in the next three days just went from 2 percent to 40 percent, and tell us why.”

In the meantime, more than 80 percent of the hospitals in the United States that treat babies with HLHS have requested CHAMP devices for their patients. Seattle Children’s Hospital is the team’s first beta site for the app, which deployed there in January.

Children’s Mercy has philanthropic funding to provide national distribution for 400 Surface tablets, which would cover 800 patients a year for the typical six-month monitoring periods between the two critical surgeries for HLHS infants.

“Early detection is the most significant aspect of this app in reducing mortality,” Shirali says. About three quarters of the fatalities of babies with this disease happen unexpectedly at home.

The first couple of years look promising – a study of Shirali’s patients using the app shows that out of 44 unplanned readmissions to the hospital, 13 were based on information picked up through CHAMP that hadn’t been noticed by the caregiver at home. Several of the babies wouldn’t have survived otherwise, Shirali says.

“I’m still very much aware of my baby’s needs and triple-checking everything, but I feel more comfortable now with this app, because if something doesn’t look right, we get a phone call even if I haven’t noticed,” Parkinson says. “And any time we have a concern, they tell us to send in a video, even if it’s the middle of the night.”

The video capability, at first an afterthought, has become indispensable. Erickson says it was only added to the app because the tablets came with built-in cameras, and the team thought they might as well use them. Now, she says, nurses depend on seeing footage every day.

“The videos opened our eyes to a whole new dimension of care,” Shirali says.

Babies’ visits to doctors’ offices aren’t usually a happy scene. Often the baby is crying and the parent is stressed. By recording the baby at home every day, when it’s peacefully cooing at its mother, it’s much easier to notice changes in behavior or appearance, such as heavier breathing or pale skin, that could indicate medical duress, Shirali says.

Stroup and his IT team at Children’s Mercy had to work through the regulatory process of getting the app approved for use at other hospitals, along with the business agreements covering security and multi-facility use. The group has started off “slowly and carefully” to make sure everything is operating properly in the highly regulated healthcare field, Stroup says.

“We focused a great deal on security, making sure the facility can only see its own info and that sort of thing,” Stroup says. “We make it seem pretty simple, but behind the scenes it’s pretty complex.”

The program has worked well in Seattle so far, and now Children’s Mercy is starting to partner with Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, on its way toward rolling out CHAMP to 40 other hospitals around the country, says David Westbrook, the senior vice president for strategy and innovation at Children’s Mercy, who shepherded the program through its bureaucratic approval process.

Typically, as many as a quarter of babies with this disease don’t survive, so with the 100 percent survival rate during the first couple of years using CHAMP, Westbrook says, the hospital felt a moral obligation to propagate it. Children’s Mercy intends to develop a whole portfolio of technology like it for patients with various diseases that require risky interventions and ongoing monitoring at home, he says.

“We didn’t develop the program with the vision of expanding to many facilities; we just developed the best solution for our patients, and then we found out it seems to be the best solution for everybody’s patients,” says Stroup. “It’s been a very exciting thing.

“We’ve worked very hard on this solution for four years, and to see it begin to come into reality, it’s probably one of the best things I’ve ever been involved with in my life, to feel you could help not only your own children but kids around the world.”