How your humble household water heater just might save the planet

On Oahu’s western shore, not far from relaxed packs of sun-soaked tourists playing in the surf, 499 household machines never stop working and never get vacation.

They are tirelessly talking and constantly conserving. They are offering a nonstop peek at tomorrow’s power grid – a cloud-based network fueled by sun and wind.

They are humble water heaters.

But these 499 units are special. All linked to the Internet of Things and tucked into a cluster of apartments, the devices provide a global blueprint to wean off fossil fuels, consume only renewable energy sources and, ultimately, help save the planet, say the people who created them.

“Hawaii is presenting a postcard to the future, showing the rest of us how electric grids are going to be operating across the world over the next decades,” said Paul Steffes, CEO, president and chairman of Steffes Corporation, a leading provider of innovative energy management and heating solutions.

The North Dakota-based manufacturer designed those 499 connected appliances, called Grid-Interactive Electric Thermal Storage (GETS) water heaters. The fleet leverages the Microsoft Azure Cloud to serve as a giant, community battery while also doing its daily dirty work: warming showers, sinks and rinse cycles for the residents at Kapolei Lofts on Oahu.

His company collaborated with Mesh Systems, which built the solution in Microsoft Azure to connect each heater, allowing information to flow from the devices to the cloud to the grid operator, Hawaiian Electric, which then orchestrates the small, Kapolei network.

“We know it’s a game changer,” said Richard Baxter, co-founder, president and CEO of Mesh Systems, headquartered in Indiana. “It’s an application near and dear to my heart. I’m a big fan of renewable energy. The problems with fossil-based generation are only going to get worse. We need a better solution. We feel good to be part of it.”

Didn’t know your ordinary water heater packed such a planetary punch? Turns out, they’re an ideal tool for transformation precisely because they’re so common.

Electric water heaters account for up to 40 percent of the residential demand on the world’s energy grids, Steffes said. The household appliances already come equipped with electric resistors capable of rapidly reacting to excess energy. In fact, excess energy represents the largest technological barrier to nations and utilities seeking to fully tap the potential of solar and wind.

Most people are familiar with energy conservation efforts – driven by high fuel prices, low supplies or, in recent years, calls to cut the burning of fossil fuels, which dump carbon into the atmosphere and harm the climate.

But clean energy sources like solar and wind power carry their own complexities. The world’s power grids were built to handle predictable power supply and consumer demand. Solar and wind are anything but predictable. During lengthy stretches of blazing sun and blustery days, solar panels and wind turbines capture more energy than the grid can absorb and regulate. Surplus energy sent into the grid could overwhelm the system, making it unstable and damaging sensitive equipment.

This explains why you may spot wind turbines at full stop on a gusty day – there’s simply no room on the grid at that moment to ingest and use that extra energy. Windmills are paused and all the energy flowing in the breezes goes uncaptured. At the same time, energy collected by solar panels gets discarded.

“The challenges grid operators always face is managing supply to real-time demand,” Baxter said. “We know renewables are peaky – often the wind blows when the sun is shining. Without storage on the grid, those renewable sources are not utilized and are wasted.”

“Utilities are hungry for something that can balance the grid,” Steffes said.

The fix? A huge battery. Enter the smart water heaters.

To conduct the Hawaiian pilot project, the builder of Kapolei Lofts worked with the local utility operator, Hawaiian Electric, to outfit all 499 units with GETS Hydro Plus water heaters. The devices each hold 52 gallons. Other Steffes models have a capacity of up to 120 gallons. The units typically cost about $300 more per unit than a comparable standard heater, Steffes said.

Key features include a well-insulated jacket that protects the heat level for hours, boosting a tank’s capacity to stockpile more thermal energy than a typical family uses each day. That extra energy is, in turn, stored for later use, turning the device into a battery that can hold 15 to 25 kilowatt-hours. The average water heater uses about 12 kilowatt-hours per day, according to various estimates.

Meanwhile, sensors on each tank talk via the Azure cloud to Hawaiian Electric, revealing the precise quantity of the heater’s water levels at any given minute and ensuring a core promise: “No one runs out of hot water,” Steffes said.

How do these devices form a collective, big battery? And how does that battery enable more complete use of renewable energy sources?

On days when solar panels and wind turbines capture more energy than the grid can accept, an automated control signal, originating at the utility, directs the network of smart heaters at Kapolei to absorb and thermally store some of that excess energy. Consequently, wind turbines can keep spinning and grabbing energy from the air.

In each of the 499 homes, tank water is heated to more than 120 degrees, higher than the normal temperature for residential use. A mixing valve then churns that super-heated water with cold water to allow for safe use in faucets, showerheads and tubs.

“There is a maximum limit to how much thermal charge each water heater can hold, and managing this across the entire network of water heaters is part of what we do in the Azure cloud,” Baxter said.

“A single water heater doesn’t constitute an energy load that’s of any interest to a utility. It’s only when you can aggregate then command and control a network of those heaters that you begin offering a load resource that utilities need – and give them the ability to integrate renewable energy that would otherwise be wasted,” Baxter added.

When skies are cloudy or the air is still, the water heater network is told not to draw grid power but rather to draw from the thermally stored (superheated) water in the devices to provide ample hot water.

“Embedded software in the water heater estimates the expected usage by learning the hot water habits of the apartment’s residents,” Baxter said. “After conservatively accounting for the needs of the homeowner, the excess thermal storage capacity is communicated to the cloud where it’s subsequently aggregated and communicated to the grid operator.”

Hawaii offers more than a pretty backdrop for the pilot project. Oahu’s plentiful sun and air streams produce rich supplies of clean energy. Local grid operators are also motivated. Hawaii has a new law directing the state’s utilities to generate 100 percent of their electrical sales from clean renewable resources by 2045.

“It’s going to take some transformation,” said Olin Lagon, CEO of Shifted Energy. His Hawaii-based company retrofits electric water heaters with gird-interactive controllers. Shifted Energy also worked with Hawaiian Electric to deploy the 499 GETS heaters at Kapolei Lofts.

Hawaii can reap vast financial and environmental benefits, Lagon said, by evolving its grid to fully feed from solar and wind.

“When the wind’s blowing and we throw it away, we have to burn oil later when we need that electricity, raising rates for everybody,” Lagon said last summer while speaking at the Microsoft Worldwide Partner Conference in Toronto.

Hawaii spends about $6 billion each year to buy imported oil – more than $4,000 for every person living in the state, according to Hawaii Gov. David Ige. That cost would go away with an all-clean-energy diet. So would the carbon cost to the atmosphere.

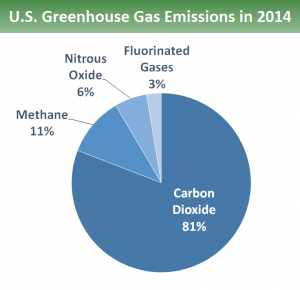

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is one of the greenhouse gases that circulate above and trap heat in the atmosphere, warming the planet by “thickening the Earth’s blanket,” reports the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. CO2 enters the atmosphere when utilities and people burn fossil fuels, including oil, natural gas and coal, as well as solid waste, trees and wood products.

Hawaii aims to stop adding to that problem – with its growing army of smart water heaters.

“The potential is incredible,” Lagon said. “In Maui, if we switched just one percent of our load to wind, we would reduce our load by 40,000 barrels, that’s about 38 million tons of CO2.”

He sees that impact spreading well beyond the islands.

“This is going to absolutely transform grids worldwide,” Lagon said.

In the U.S. alone, there are 45 million electric water heaters. If utilities connect those devices to the cloud, forming an enormous battery that keeps wind turbines spinning and stabilizes the grid, the nation would gain the equivalent of more than 200 clean power plants, Steffes said.

The wind carries hope.

Illustrations by Perfect PlanIt, Inc.