Museums and machines: Curating tech to democratize art, culture, history and science

These aren’t your father’s museums. Heck, they’re not even your big sister’s.

From digital pens that let visitors virtually take collections home with them to artificial intelligence that links modern photographs with historic paintings, the world’s cultural institutions are democratizing technology to help them stay relevant in a connected world.

Traditionally, museums have had a conservative mission, charged with preserving humanity’s greatest treasures in order to pass them on to the next generation. The digital age is altering that focus, as institutions look for new ways to appeal to modern lifestyles.

“We started off building museums as the way to warehouse the things we care about, sort of like an attic, and then we shifted into being a platform for education,” says Micah Walter, with Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City. “Now we’re realizing that in order to sustain ourselves and be relevant today, it needs to be about the visitor experience, not the academia behind it, and technology is one way of helping to provide that shared experience visitors are looking for.”

Museums have responded to the shift from the top down, adding new titles to their management lineups such as chief experience officer and chief digital officer.

“A lot more people from other sectors are coming in and working with cultural institutions now – from tech, business and other areas – and acting as translators,” says Peter Tullin, co-founder of Remix Summits, which runs global events bringing together leaders from different industries to foster creativity. “They’re helping museums understand what their assets and value are and helping them tell their stories in new ways by finding the right collaborators to bring them alive.”

Walter joined Cooper Hewitt about seven years ago after a career in digital imaging and technology. He is now the museum’s director of digital and emerging media.

The museum just finished an 18-month project to photograph and digitize its collection of 210,000 objects, with nearly all now available for viewing online, as opposed to the 500 to 700 items displayed in the museum itself at any given time. That’s one way to increase accessibility.

“Putting everything online makes our collection more browse-able and approachable for visitors who either can’t come here or who have come and want to see more,” Walter says.

The museum was founded in 1897 to be a teaching, working museum where designers and students could touch and study materials. Now, the institution is trying to recreate that experience in a digital way.

Every Cooper Hewitt visitor is given a “pen” device that looks like a big magic marker, and a ticket with a personal website printed on it. Press the top of the pen against the sensor near an interesting item, and an antenna adds a photo and description to a personal collection that’s stored in the device.

Users can then press the pen against digital placemats at “dinner tables” scattered around the museum to take a closer look at the items and even use them as inspiration for their own designs, using the stylus at the pen’s other end to draw on the placemat. Pictures of the thousands of items that aren’t physically displayed stream through the center of the table, like a sushi smorgasbord, and can be dragged and dropped onto a placemat. Visitors help each other explore the technology, which adds to the shared experience as they each create their own personal museums to take home, Walter says.

After the pen is dropped off at the exit, the collection – including personal drawings – is uploaded to the corresponding ticket’s website, which can be retrieved from anywhere. Some visitors have even used the digital designs they created at the museum to print 3D objects back home, Walter says. The average visitor collects about 40 items.

One of the most popular exhibits is the Immersion Room. Cooper Hewitt has 10,000 samples of wallpaper – the largest collection in North America – but it’s impossible to exhibit it all at once. So the museum covered the walls of one room with large screens and put a digital table in the middle. Visitors use their pens to choose wallpaper that catches their eye as it scrolls over the table and drag it to their placemat, which instantly loads the pattern onto the full wall. They can then add to the design or start fresh and draw their own. And they can save any patterns they fall in love with to their collection for later.

“I wish I had this in my bedroom so I could have a different view every day,” gushed Wanda Balines, who was visiting from the Bronx with her 15-year-old daughter, Tamara Castillo. Balines drew a yellow, hot-pink, purple and turquoise design on a black background, the pattern covering the wall as she sketched. Tamara’s design was I(heart)U in yellow and red. “When I was her age, nothing like this existed,” Balines said. “It’s a form of learning.”

As Tamara saved her design, she said her second visit to the Immersion Room was even better than the first, and she’s thinking about becoming a wallpaper designer. In the meantime, she also collected items around the museum that looked like styles from the 1980s – inspiration, she said, for a Halloween costume she planned to make for herself.

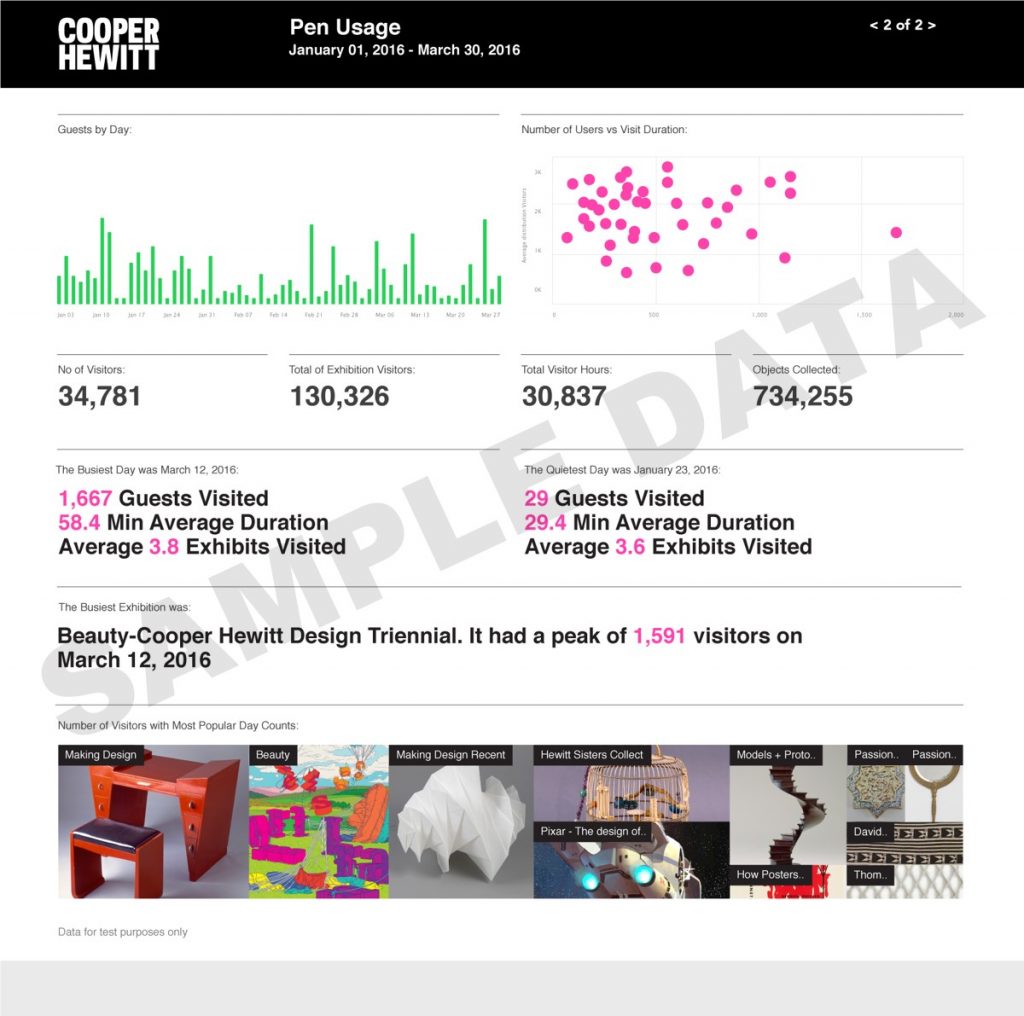

The museum is working with interactive Microsoft Power BI data visualizations to better understand visitors’ behavior and help with exhibit planning and funding decisions. It’s been a successful year – visitation has exceeded all of Cooper Hewitt’s goals, and visitors have collected more than 10 million items.

Curators are increasingly able to create more relevant exhibits, using machine intelligence and application programming interfaces along with publicly available demographic trends and surveys of a museum’s members.

“It’s very democratizing that small organizations – even the smallest museums – now have access to this type of capability,” says Fred Warren, creative director for Microsoft’s Customer Digital Services team, who helped support Tate Britain’s IK Prize project. “Cognitive services allow museums and businesses to try new ways to derive inference about their consumers and guests, helping them bring new perspectives to their collections and catalogs.”

Tate Britain’s first IK Prize, awarded for digital creativity coming from outside the museum industry, was given in 2014 to a group that unleashed robots with cameras in the museum’s galleries at night. People could log in and guide the robots toward whatever interested them, or watch through the eyes of other users who had control. It was a way to bring British art from the Tate collection to a broader audience, says Tony Guillan, the award’s producer, especially since most visitors to London focus on the most famous of the institution’s four galleries, the Tate Modern.

“One guy was on a train in South America, and he tweeted a photo of himself watching the robots explore our galleries,” Guillan says. “Here’s a guy on the other side of the world, and he might never come to London, but there he is learning about British art on this train. It was a highlight for me.”

Museum leaders say expanding accessibility through online efforts actually augments rather than cannibalizes their ticket sales. People find out about collections online and are inspired to seek out physical, shared experiences with friends and family.

“There’s no substitution for engaging with artwork in the flesh,” Guillan says. “I was never a big fan of Van Gogh until I went to an exhibit and actually saw his paintings in person.”

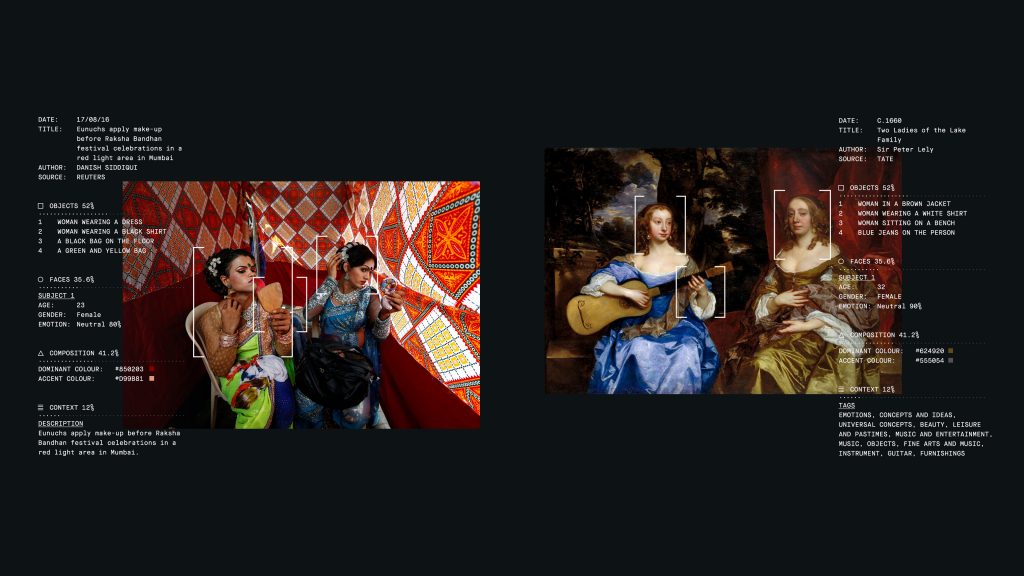

This year’s winning IK Prize team, the Italian group Fabrica, used Microsoft Cognitive Services and software by JoliBrain to create an artificial intelligence program that compares 30,000 images of British art from the Tate collection to photographs of current events as they stream in throughout the day on the Reuters Pictures service. When the machine finds visual and thematic similarities, it publishes the pair of photos in an online gallery. Visitors at the museum can select alternative comparisons if they disagree with the machine’s match, helping it learn and improve as it goes. The “Recognition” project runs until Nov. 27.

“It makes you think differently about artwork and history,” Guillan says. “It also makes you think about what happens in your brain when you look at an image. You realize the machine is only so advanced and can only use certain criteria to evaluate images, but maybe it’s picking up something you didn’t. If it compares images that no human would ever compare, does it have a serendipitous meaning to you?”

Technology is changing museums’ relationships with their visitors, regardless of whether the organizations want to embrace it or not, Remix’s Tullin says.

“It’s no longer the cultural institution as curator, where they define how the user uses the space or content,” Tullin says. “Everyone has a smart phone and can decide what to do based on what tools are available to them. If someone wants a virtual-reality experience, and you’re not providing it, they’ll just go elsewhere.”

Seattle’s Museum of Flight embraced virtual reality out of sheer necessity. Restoration groups said they could no longer repair the damage done by visitors scampering through fragile aircraft like the 73-year-old B-17 Flying Fortress bomber.

Plus, it wasn’t feasible to put elevators up to every plane in the museum’s Aviation Pavilion, which is the size of two football fields and has a roof but no walls. Exhibit developer Peder Nelson wanted to provide handicap access while protecting the planes’ most sensitive sections, and he knew audiences expect more than simple videos now.

Nelson worked with Microsoft to develop 360-degree photographic tours loaded onto Surface Pro 4 tablets the docents now carry with them. The tours can be shown to anyone who can’t make it up the two flights of stairs into the first Boeing 747 ever built, for example, as well as to those who get that far but aren’t allowed up another delicate, winding staircase into the jumbo jet’s iconic hump. The photography is hosted on the Microsoft Cloud and can be turned into a virtual-reality experience either at the museum or at home, through a device that clips onto a smart phone.

The Australian Museum in Sydney is working with Microsoft HoloLens to include mixed-reality, interactive exhibits as it refurbishes a gallery next year that was first built in 1855. Steven Alderton, the museum’s director of programs, exhibitions and cultural collections, can barely contain himself when he talks about the project’s possibilities.

“Museums have all these collections, but how do you interact with them?” Alderton says. “Mixed-reality technology helps you do that and lets the user steer their own experience. That’s a very big difference.

“We’re moving away from the audience being passive in a museum building to being interactive and participatory and curating the experience themselves, both inside the museum’s walls and in people’s homes – and pockets.”

The Australian Museum aims by early next year to have a project ready that uses Microsoft simultaneous translation technology to help preserve Aboriginal languages, which are disappearing by the hundreds after the country’s history of not allowing indigenous people to speak their own languages. The museum has translated 10,000 sentences so far, on its way toward a million sentences before it will go public and expand.

“With their phones and the Microsoft translator app, people will be able to hold so much knowledge and power and energy from Aboriginal languages and culture in their pockets now, and that will go a long way to sustaining Aboriginal culture,” Alderton says. “It’s a very powerful thing.”

Christine Reich’s goal as vice president of exhibit development and conservation of the Museum of Science in Boston is not just to teach visitors about facts but to create experiences that foster an interest in scientific learning and habits of mind that help visitors think like mathematicians, engineers and computer scientists.

“We want technology to help us facilitate new ways of thinking about the world, but we want it embedded in the experiences so it’s seamless,” Reich says. “We don’t want the visit to be about the interaction with technology but about the experience itself, so the technology needs to be almost invisible.”

The Museum of Science plans to transform its 40-year-old Blue Wing with those goals in mind over the next 10 years. The three-level wing sits on a dam spanning the Charles River between downtown Boston and the Cambridge neighborhood. Space is limited and geography is symbolic, with hubs of innovation on each side of the museum.

“The new skill we want to highlight is to imagine possible worlds,” Reich says. “And we need to do the same ourselves, because with a 10-year plan, we need to build in flexibility for whatever technology might be available down the road.”

That can be a problem for the non-profit museum industry, which is usually behind technological advances and visitors’ expectations, the Museum of Flight’s Nelson says. Private companies increasingly are partnering with the institutions to help them keep up. But museums need to be sure they retain full control of the exhibits and are the authoritative voice on content, Nelson says.

Reich’s team visited Microsoft’s Redmond, Washington, headquarters this year to learn about ways technology can help redefine and enhance a museum experience. Her group is now working with the company to customize the Blue Wing so exhibits can provide enough challenge to foster learning for everyone, from single visitors to large groups, and infants to seniors, she says. Part of the work involves rethinking how visitors interact with computers, potentially using whole-body movements and objects as ways to enter information into systems, while using projectors to turn surfaces into a multitude of screens.

The “Engineering in a River System” exhibit, which opened in March, already relies on some of that technology. In an alcove across from a window overlooking the Charles River, a landscape is projected onto a table with tactile objects surrounding a flowing digital river. Starting on the left, a kayaker floats down the river between houses that need electricity. Visitors can install different-sized hydroelectric dams – like the one the museum sits atop – using boards with magnets that trigger the river to react in corresponding measure.

The kayaker bumps into the dam with a “bonk” sound and gets stuck, and fish get trapped on either side, but the houses light up.

At stations downstream, visitors make decisions about pest management of crops, fish passages, land use and even a sewer system. If the board is chosen that dumps raw sewage into the river, the water there changes from blue to putrid, boaters are turned away and fish die. But if there’s no sewer system, the toilets in the house at that station – physical structures that can be touched – back up with projected sewage that spills onto the bathroom floor.

Visitors are encouraged to explore what happens depending on whether the economy, the environment or recreation are valued highest.

“This is a great example of the right mix between technology and a hands-on, tactile interaction,” Susanna Paille said as she swapped boards to try out different crop-spraying scenarios during a visit from Salem, Massachusetts. “It’s very visual so it draws you in, but it’s also physical, so it brings you more engagement by using your body and senses. That’s something we really need in a culture where we’ve gotten so used to digital touch screens.”

Top photo by Matt Flynn © 2015 Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.