New Bühler machine uses the cloud to find the needle in the haystack – or the poisonous kernel in a truckload of corn

Talk about trying to find the proverbial needle in a haystack – how about a single kernel in a truckload of corn?

Just one grain infected with a highly carcinogenic mold called aflatoxin can be all it takes to poison the whole harvest and sicken or even kill people and animals, not to mention the waste of having to throw out the lot when contamination isn’t found in time. Aflatoxin often can’t be seen, smelled or tasted, and it’s not destroyed by heat – so cooking contaminated food doesn’t make it safe.

“Aflatoxin isn’t exactly a household name, but it’s one of the biggest global pains,” says Beatrice Conde-Petit, food safety officer for Swiss technology firm Bühler AG. “And it’s a silent threat. You don’t even know you’re being poisoned.”

Since consumers can’t tell if their food is infected, the onus is entirely on growers, harvesters and processors – more of whom are having to fight the mold as it expands north amid climate change that stresses crops and makes them more susceptible. So the stakes are high for the new corn processing system Bühler engineers developed as part of an innovation challenge.

LumoVision is a data-driven optical sorter that’s connected to the cloud for data analysis and uses powerful new cameras and ultraviolet lighting to hunt for hidden infections. The system is such a breakthrough and fits so well with the company’s mission to reduce waste and increase food safety that executives aim to get it to market by year-end, in half the time it would normally take.

Ingestion of high levels of aflatoxin can be fatal, and chronic exposure can result in serious health problems, according to the International Food Policy Research Institute. There are about 155,000 new cases a year of cancer caused by aflatoxin – it’s the leading cause of liver cancer in developing countries. And half a billion people in areas that don’t have food safety regulators, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency, are being poisoned by it. The toxin stunts children’s growth both physically and mentally – starting in utero, if a pregnant woman eats contaminated food – and the damage, once done, can’t be reversed.

Ideas for keeping aflatoxin out of food have been studied as long as its risks have been known, but technology to implement them has been limited.

In 1960, more than 100,000 turkeys in the U.K. mysteriously and suddenly died. Scientists were flummoxed by the “Turkey X” disease until they discovered the culprit: highly toxic mold had infected the birds’ feed, peanut meal from Brazil.

In humans, exposure to that mold, aflatoxin, doesn’t usually cause acute contamination – where you eat infected food and feel ill. The potentially fatal effects more often come from chronic exposure and steady consumption. That’s particularly problematic since grain is the cornerstone of global nutrition, and corn, or maize, is the most grown grain on the planet. It’s a staple in African and Central American diets and the main source for livestock feed around the world. And the danger goes beyond the obvious: Aflatoxin seeps into milk when dairy cows eat contaminated grain, for example.

By 1965, Bühler had a patent for a sorting machine to keep aflatoxin out of food and animal feed, says Ben Deefholts, Bühler’s senior research engineer for digital technologies. But it was so slow that it wasn’t commercially viable – in regions with food safety regulators, it could be cheaper to discard an infected lot than try to sort it, and elsewhere, the contaminated food was often simply eaten.

When aflatoxin showed up in Italian maize in 2012 after a prolonged drought, Deefholts and some colleagues spent the summer trying to come up with better solutions to combat it. They used existing technology Bühler engineers had developed for other crops to set up a new cleaning system for corn. It blew away the dust, since it can be highly contaminated; separated the grains by density, to remove broken ones that were more susceptible; and optically sorted the kernels, taking out any that were visibly deformed or discolored.

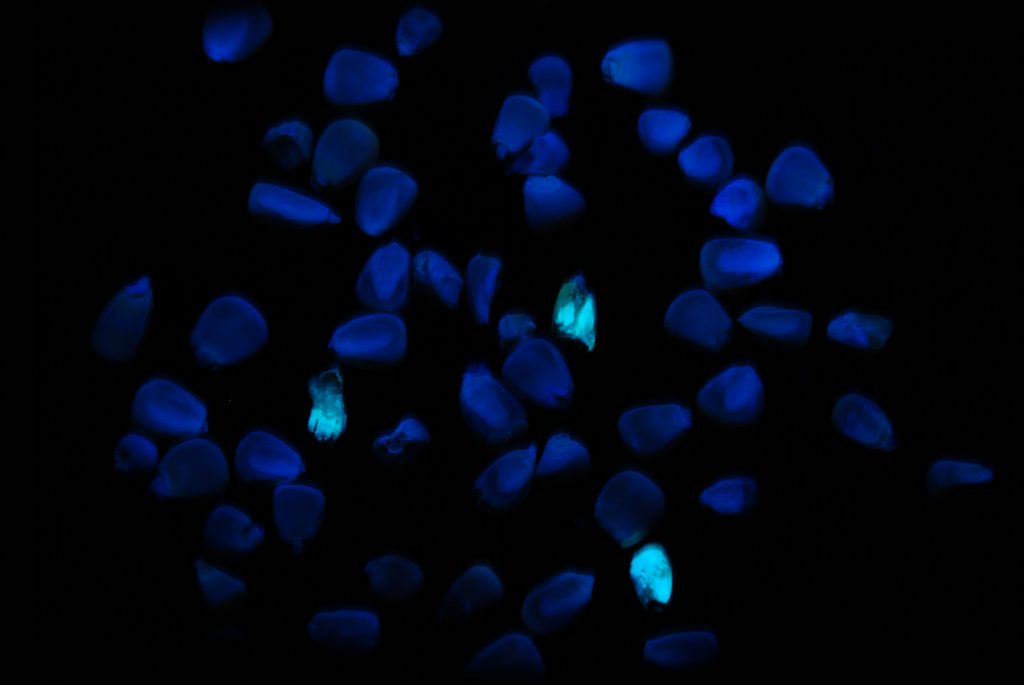

Those methods still resulted in a lot of healthy food being wasted, though, and they weren’t able to address invisible infections, which can’t be seen by the naked eye – or camera – but do show a green or yellow glow under UV lights. So when Bühler challenged employees to an innovation competition in 2016, Deefholts knew exactly what he wanted to work on.

He and his colleagues combined the company’s R&D expertise, honed over 70 years of developing grain sorting solutions, with the new power of the cloud and data analytics software, as well as new camera and UV lighting technology. Their system is being introduced at the Hannover Messe trade show for industrial technology, which starts Monday in the northern German city, and then will be tested within the MycoKey network, a European group founded recently to tackle mycotoxins, of which aflatoxin is the most dangerous. Bühler aims to have LumoVision in commercial use by the end of the year.

The company found an ideal test customer in Italy. Capa Cologna had struggled with aflatoxin in the 2012 drought, so the agricultural cooperative grew concerned last year when weather turned hot and dry again – ideal conditions for the mold to develop. They jumped at the chance to try out LumoVision.

“We are very excited by Bühler’s new development,” says Capa Cologna’s Damiano Destro. “The new machine should allow us to sort all our incoming product, reducing losses and most importantly improving food safety.”

Word of the test spread quickly, and Bühler’s Italian salesman got “a tidal wave” of calls from other agricultural companies asking about the new system, Deefholts says. “Since LumoVision does all the work by itself, and the efficiency is quite high and the waste quite low, it’s going to make quite a big difference.”

With LumoVision, corn gets fed from a truck into a hopper above the 6-foot-tall machine, and a vibratory feeder sends it into a chute where it accelerates to 3.5 meters (11.5 feet) a second as it flows in a single layer. A camera on each side uses UV lights to illuminate the grains, looking for the telltale fluorescence of aflatoxin infection. High-speed valves operating compressed air jets – which can open or close in a thousandth of a second – simply shoot any contaminated kernels into the rejects bin, letting the rest of the healthy corn pass through into storage or shipping containers.

It’s so fast that if someone were holding an open bag of corn and turned it upside down, it would be analyzed and sorted by the time a single kernel hit the ground. The system can process 10 to 15 tons of maize – or an entire truckload – in just one hour.

Weather patterns at the time of harvest, the health of other lots harvested in the area and other relevant data points – including information from the cameras as they watch the grains pass by — are all uploaded to Microsoft’s cloud and analyzed to provide a real-time risk report on the crop and guide the system’s processes. If the risk is minimal, sorting can be paused while monitoring continues. If the risk rises, sorting automatically restarts.

“This came at exactly the right time for us, because we were just starting our digital journey toward data analytics and the Internet of Things,” says Stuart Bashford, Bühler’s digital officer. “The general concept for something like this had been around for years, but the technology never existed before to make it commercially viable. But now it’s all come together in this incredibly rewarding project.”

LumoVision’s real-time identification and elimination keeps toxins from spreading and infecting even more kernels. And it reduces the amount of healthy grain that gets wasted in the process to less than 5 percent, from as much as 25 percent with existing machines.

It only works with maize now, but Bühler envisions expanding it to peanuts, rice and dried fruit as well – other foods at high risk of aflatoxin infection.

For countries and regions with strong food safety regulators, aflatoxin is more of an economic problem, because contaminated food can’t be sold. But in other areas, where there’s no choice but to eat tainted food or go hungry, it has become a severe health problem. In Africa, 40 percent of liver cancer is thought to be caused by aflatoxin. And that’s what gets Deefholts so excited that his sentences are peppered with verbal exclamation points, even at the end of a long day.

“We’re not only going to get economic results, but hopefully we can transform and save lives at the same time,” he says. “It’s the most exciting and valuable project I’ve worked on in my 40 years with the company. It’s a really big thing.”

Top image: Kernels of corn infected with aflatoxin glow under UV lights. (Photos courtesy of Bühler)